![]()

Chapter One

INTRODUCTION

The shortest distance between a human

being and truth is a story.

–ANTHONY DE MELLO

After finishing high school, Bhibuti attended Bible college for two years to prepare for ministry. Now he was eager to preach the gospel to people in the villages of the interior of his country. But when he finally arrived at his station and began preaching, the unschooled villagers seemed baffled by his sermons. They puzzled over the theological terms he used; after awhile they gave up trying to understand him. Some would come to the church for the singing and then slip out as soon as the sermon started.

However, their response changed dramatically when Bhibuti started learning biblical storytelling. The same villagers who had been bored with his sermons listened delightedly to the stories he told them from the Bible. They found they could understand the spiritual themes and soon began growing in their Christian faith. Church members told him, “Because you are telling us the stories, now we can understand everything. Before you were not telling the story, and we were not understanding anything.”

Just as exciting to Bhibuti was the realization that the believers had started telling the stories to their friends and neighbors. He appointed some of them to go tell the Bible stories in other villages. As their listeners heard the stories of how God had blessed people just like them, faith was birthed in their hearts and many believed in Jesus. New congregations of believers began to spring up and now Bhibuti is pastoring a dynamic, growing church.

BACKGROUND

In 1994 the Indian founder of a large indigenous church-planting agency asked my help in training the midlevel leaders of his rapidly growing organization.1 Concurrent with this, my wife and I began an extended study program that culminated in earning masters degrees in Intercultural Studies at Fuller Theological Seminary School of World Mission.2

Although I had served as a missionary in Latin America for many years, I was still unprepared for the complexity of India’s worldview and its social mosaic. I found that working in this context presented vigorous new challenges to communicating and teaching the Bible. Given my prior missionary experience and recent study at Fuller, I somewhat naively assumed that I had mastered the communication skills that would be needed. I worked hard to prepare lessons that were simple and comprehensible, seeking to offer the Christian workers practical training that would help them improve their field practice. In spite of their limited formal schooling and consequent unfamiliarity with western modes of learning, most seemed to enjoy the workshops and welcomed the instruction.

However, hints soon began to emerge that all was not well. It seemed that little of what I taught was being put into practice by the workers. When I asked them simple questions requiring minimal deductive reasoning they were unable to respond. Slowly I began to sense the huge barrier that exists between people with a preference for oral communication and print-oriented communicators like me.

At first it was tempting to blame the learners or even spiritual forces for this failure to communicate. But eventually I became convinced that I needed to find a better way of communicating with them. This began my quest for a more effective teaching method.

I tried alternative learning techniques like active training and role play; I added goal setting and accountability procedures, and sought other ways to make the training sessions more effective. These changes helped the seminars become better at transferring content that could be remembered by the learners and which they could put to use in their fields. But the equipping structure was still a western model that depended mainly on lecture.

This led to a bigger concern: if I taught the workers with techniques that were foreign to their context, how would they themselves learn to teach in ways that fit their context? In other words, to be reproducible the pedagogical model itself had to complement the learning styles found in the culture. If the pastors were unable to transfer the knowledge they had gained, how would the churches they served ever become strong and self-reliant?

This need for a more compatible equipping model eventually led me to begin developing the oral Bible training program. My studies at Fuller had laid a foundation in the disciplines of missiology, cultural anthropology and Christian communication which informed this project. Research in Fuller Seminary’s McAlester Library in Pasadena, California and at the University of South Alabama in Mobile helped advance the search for a more user-friendly approach for oral cultures. I was looking for Bible teaching methods that were compatible with oral learning styles, and which would allow biblical knowledge to flow all the way to the fringes of each people group regardless of their level of schooling.

To my surprise, storytelling began to emerge as the strongest contender. Shortly afterward, I started testing biblical storytelling among some of the same oral communicators I had worked with previously. In what turned out to be a four-year pilot project, 56 men and women of all ages learned to tell significant portions of the Scriptures in story. Each storyteller was also required to train another person to tell the stories.

Building on the experience gained through the pilot project, in 2006 I started a second generation oral Bible program in a different region of the country. Sixty full-time Christian workers from half a dozen states enrolled in a structured two-year program to be trained as biblical storytellers. This book describes their experiences and tells what I learned among them during 20 months of field research.

In this second phase I also completed a D.Min. program at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. My mentor was Tom Boomershine, the author of Story Journey: An Invitation to the Gospel as Storytelling (1988) and founder of the Network of Biblical Storytellers. Telling God’s Stories with Power grew from the doctoral thesis I completed in November 2007.

PURPOSE

The intent of this project was to develop a storytelling equipping model that would promote relayed transmission of the Scriptures among peoples of oral cultures.

In literate cultures theological learning typically focuses on transforming knowledge and meaning by restructuring it in new ways. Oral communicators do not understand this because it relies on a cognitive style that is only possible for those who have well-developed literate skills. Grant Lovejoy explains, “Without the technology of reading and writing, primary oral communicators dare not break what they know into hard-to-remember abstract lists or categories. They resist literate-style analysis because they cannot be sure to get all the pieces back into proper place through the use of memory alone. Hence they communicate in holistic rather than analytic ways.”3

An oral communicator’s way of using what he or she learns is not to manipulate it mentally but to apply it to life in concrete ways. Oral communicators typically ground their cognitive styles and learning patterns in concrete experiences related closely to the lifeworld in which they live. This is known as concrete-relational thinking. Walter Ong explains, “In the absence of elaborate analytic categories that depend on writing to structure knowledge at a distance from lived experience, oral cultures must conceptualize and verbalize all their knowledge with more or less close reference to the human lifeworld, assimilating the alien, objective world to the more immediate, familiar interaction of human beings.”4

The contrast between concrete and analytical communication can be illustrated by considering the meaning of statistics. What does it mean to talk about a 90 mph wind? Only after having spent ten hours in a hurricane and then walking outside to see the destruction the next day can it be properly understood. What does 40 degrees below zero mean? How about 12 inches of rain in four hours? Concrete descriptions of these events stand out in contrast to analytical ways of stating them.

Concrete-relational thinking may use metaphors of familiar objects to express thoughts, feelings, or quantities that are not easy for oral learners to grasp otherwise. Furthermore, while an analytical thinker generally deconstructs and analyzes the component parts, a concrete-relational thinker tends to view and talk about things holistically.5 As far back as 1923, Lucien Levy-Bruhl described the wide divergence between the thinking styles of westerners and concrete-relational thinkers:

The two mentalities which encounter each other here are so foreign to one another, their customs so widely divergent, their methods of expressing themselves so different! Almost unconsciously, the European makes use of abstract thought, and his language has made simple logical processes so easy for him that they entail no effort. With primitives, both thought and language are almost exclusively concrete by nature.6

Surprisingly, the Bible is uniquely suited for communicating with such oral peoples. Tom Steffen points out, “The concrete mode of communication dominates both Testaments and is conspicuously evident in all three basic literary styles [narration, poetry, thought-organized].”7

When the church was not as far removed from its oral roots as it is today, this concrete way of thinking and expressing ideas was valued. In 1785 a young William Carey was seeking ordination from the Baptist Church in Olney, England, but he was turned down after the members heard him preach. They decided he needed a period of probation. Mr. Hall of Arnsby, criticizing the attempt, said, “Brother Carey, you have no likes in your sermons. Christ taught that the Kingdom of Heaven was like to leaven hid in meal, like to a grain of mustard, and etc. You tell us what things are, but never what they are like.”8 Whereas Carey was speaking in ideas, Mr. Hall was describing the learning preference of oral communicators who understand best when things are taught in concrete ways related to that which is already familiar to them.

Louis Luzbetak tells of an Indian religious man who was complaining to a group of missionaries about the methods they were employing: “You say that you bring Jesus and new humanity to us. But what is this ‘new humanity’ you are proclaiming? We would like to see it, touch it, taste it, feel it. Jesus must not be just a name, but a reality. Jesus must be illustrated humanly.”9

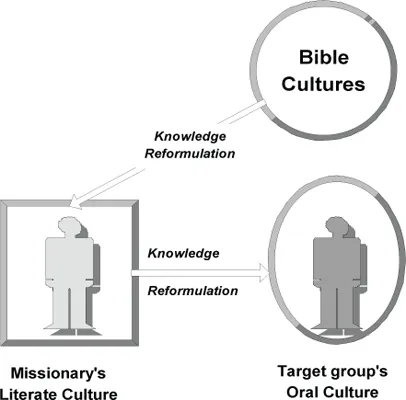

The thesis of this research is that storytelling is a more effective way of relaying Bible knowledge in oral contexts than methods that grew from print technology. From the time of its post-Reformation renaissance, Christian missionary work was carried out according to a literate model. It has largely continued to base its strategies on literacy right up to the present time. Figure 1 shows the complexity of using such a literate transfer model to reach oral communicators with the gospel.

Figure 1. Literate Transfer Model

Because the knowledge of God was originally revealed in Bible cultures that were predominantly oral, it was necessary to reformulate the message twice: once into our literate culture and again into present-day oral cultures. This placed a great handicap on the missionary and also a heavy burden on the oral receptor to try to grasp ideas presented in an alien cognitive style. It greatly restricted the transmission of the biblical message throughout the missionary era.

In an effort to reach Hindus by providing the Scriptures in their own vernacular, William Carey and his associates, Marshman and Ward, translated and printed the Bible in Bengali, Oriya, Marathi, Hindi, Assamese, and Sanskrit and also translated parts of it into 29 other Indian languages. In the biographical film, “A Candle in the Dark” William Carey holds his first newly printed page of Scripture in the Bengali language. Referring to the printed words on the page, he proclaims, “These are my missionaries.”1...