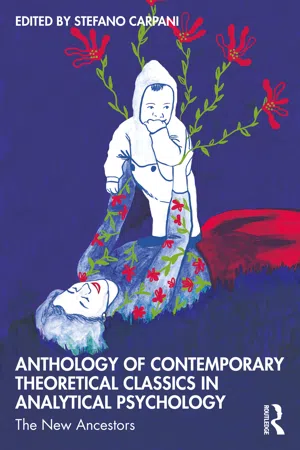

Anthology of Contemporary Theoretical Classics in Analytical Psychology

The New Ancestors

- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Anthology of Contemporary Theoretical Classics in Analytical Psychology

The New Ancestors

About This Book

2022 Gradiva Award nominee for Best Edited Book!

This anthology of contemporary classics in analytical psychology bring together academic, scholarly and clinical writings by contributors who constitute the "post-Jungian" generation.

Carpani brings together important contributions from the Jungian world to establish the "new ancestors" in this field, in order to serve future generations of Jungian analysts, scholars, historians and students. This generation of clinicians and scholars has shaped the contemporary Jungian landscape, and their work continues to inspire discussions on key topics including archetypes, race, gender, trauma and complexes. Each contributor has selected a piece of their work which they feel best represents their research and clinical interests, each aiding the expansion of current discussions on Jung and contemporary analytical psychology studies.

Spanning two volumes, which are also accessible as standalone books, this essential collection will be of interest to Jungian analysts and therapists, as well as toacademics and students of Jungian and post-Jungian studies.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Chapter 1

no hope, because he is disillusioned by the world … no love, but only sexuality; no faith, because he is afraid to grope in the dark; [and] … no understanding, because he has failed to read the meaning of his own existence.”66Jung Vol. 11, §499.

I saw myself, not with the eyes of the body, but those of the spirit [nicht mit den Augen des Leibes, sondern des Geistes], coming toward myself on horseback on the same path, and, to be sure, in clothing I had never worn: it was bluish grey with some gold trimming. As soon as I shook myself awake from this dream, the figure vanished.(GE 4, 370)

just as your sensuous eye is a prism, in which the ether of the sensuous world, which is in itself quite self-identical, pure, and colourless, breaks into manifold colours on the surface of things [… . ] so proceed likewise in matters of the spiritual world, and from the view of your spiritual eye’.2

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Epigraphs

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The New Ancestors and the “Agenda 2050” for Analytical Psychology

- 1 Seeing With the Eyes of the Spirit

- 2 A Critical Appraisal of C. G. Jung’s Psychological Alchemy

- 3 Narcissus’s Forlorn Hope: The Fading Image in a Pool Too Deep

- 4 Complexes and Their Compensation: Impulses from Affective Neuroscience

- 5 Hesitation and Slowness: Gateway to Psyche’s Depth

- 6 The Other Other: When the Exotic Other Subjugates the Familiar Other

- 7 Jungian Theory and Contemporary Psychosomatics

- 8 Feminism, Jung and Transdisciplinarity: A Novel Approach

- 9 From Neurosis to a New Cure of Souls: C.G. Jung’s Remaking of the Psychotherapeutic Patient

- 10 The Dao of Anima Mundi: I Ching and Jungian Analysis, the Way and the Meaning

- 11 A Personal Meditation on Politics and the American Soul

- 12 On Jung’s View of the Self—An Investigation

- 13 Seeing From “the South”: Using Liberation Psychology to Reorient the Vision, Theory, and Practice of Depth Psychology

- 14 The Clash of Civilizations? A Struggle Between Identity and Functionalism

- List of Contributors

- Index