- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About This Book

In this lavishly illustrated volume, Laura Lee introduces the art of Tokyo-based digital art collective teamLab, which has soared to global fame with its electrifying immersive and interactive installations. The first of its kind, Worlds Unbound: The Art of teamLab provides a comprehensive overview of teamLab's artistic vision and achievements from its beginnings to its twentieth anniversary in 2021, and illuminates the remarkable scope of teamLab's groundbreaking art and its fundamental contribution to the pivotal field of new media art.

This original new book, the first scholarly monograph on this popular group, unpacks the popularity and success of the digital immersive environments created worldwide by the Tokyo-based collective, teamLab, from multiple perspectives and addresses the lack of critical appreciation of their work. The book includes an extensive interview with teamLab.

teamLab launched in January 2001 with five members and now comprises more than 600 individuals in a multidisciplinary collaboration of engineers, computer graphics animators, mathematicians, graphic designers, architects, artists and computer programmers.

The digital art collective has attained international celebrity for its electrifying installations that transcend boundaries between gallery, public space and popular entertainment and, judging from press coverage, ticket sales and prolific production, it seems clear teamLab's success is only on the rise. In 2018, the collective opened the MORI Building DIGITAL ART MUSEUM: teamLab Borderless, a massive technological environment in Tokyo that recorded 2.3 million visitors in its first year of operation – the world's largest annual number of visitors of any single-artist museum. The same year saw numerous other high-profile immersive exhibitions, including teamLab: Massless in Helsinki, Au-delà des limites in Paris, and teamLab Planets TOKYO, a second exhibition in Tokyo.

These were quickly followed by two new museums, teamLab Borderless Shanghai in 2019 and, in 2020, teamLab SuperNature in Macao. The vast sea of selfies that have emerged from these venues index the collective's soaring global popularity.

At the same time, teamLab's works have found art market success and have been exhibited in major museums worldwide, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC and Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), and they are part of the permanent collection of The Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, and Amos Rex in Helsinki, among numerous others. This canonization of teamLab's art belies the fact that the group did not have a traditional gallery start, and in fact teamLab has always engaged in software development and corporate work, in addition to creating artworks. The collective thus boasts an enigmatic status, spanning conventional categories and defying traditional art world pedigree. In so doing it has produced a tremendously rich body of work that speaks to several overlapping issues pertinent to contemporary art while advancing a unique artistic vision.

Primary readership will include artists, art historians and visual studies scholars who are particularly interested in the most recent media art and Japanese contemporary art.It will be an essential resource for students and scholars working in Japanese art, global contemporary art, digital art, augmented reality, expanded cinema and installation art and related fields.

It will also be of more general interest to those who have visited, or hope to visit, teamLab environments worldwide.

Frequently asked questions

Information

PART I

Chapter 1 Ultrasubjective Space

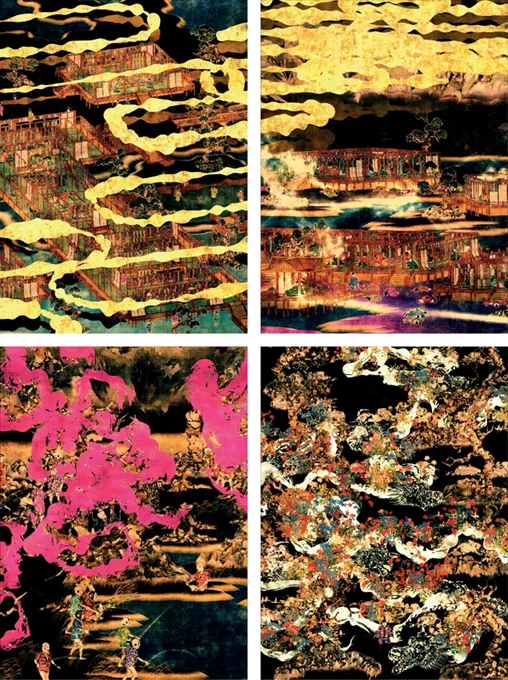

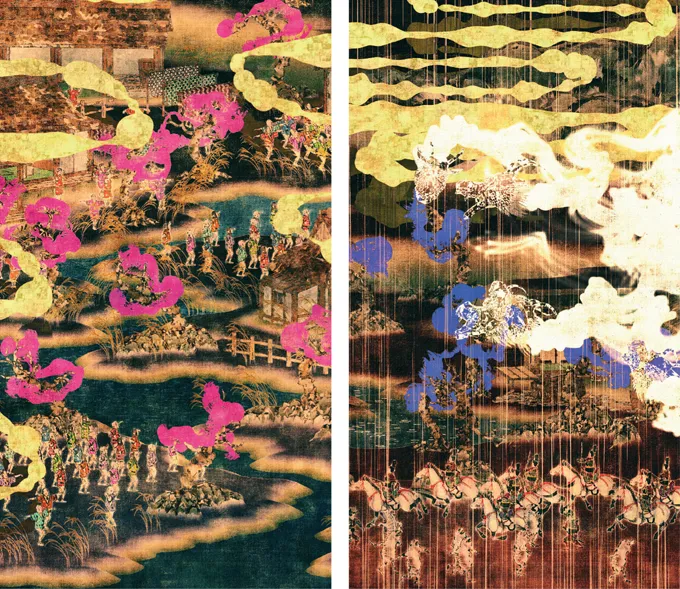

This looped narrative reimagines Japanese artistic tradition through digital animation. Notably, the work combines a focus on the pictorial surface with an insistence on the depth of the image, in effect pushing the viewer into the image while simultaneously flattening that space. Dense with Buddhist symbols, it opens with a brightly-lit white elephant walking amidst an undifferentiated azure background. A slight mist hangs in the image, which ambiguously lends it depth while also asserting its paper-like material support. And it is dotted with floating cloud formations that resemble snakelike tendrils. The framing progressively tightens on the elephant’s right eye, which opens onto a Japanese village landscape. The viewer thus enters the narrative by seemingly moving forward into the three-dimensional world of the image. Penetrating its depths, the viewer assumes a free-floating perspective, at times soaring high in the air to take in the village from an aerial view, and at other times tracking laterally across the landscape or gliding downward in front of a vaporous three-dimensional waterfall (see Universe of Water Particles). This travel within the image’s depths is set off against a coexisting visual flatness, as the work’s surface treatment echoes the Japanese ornamental technique of kirikane, which traditionally celebrated the grandeur of Buddhist images by cutting gold (or other metal) leaf into lines or small shapes and adhering them to the surface. In The Land of Peace and Bliss (2014), the gold linework similarly emphasizes planarity, flattening the three-dimensional animated objects and causing them to appear to cling to the surface of the work. This oscillating sensation of flatness and dimensionality recalls the free-floating perspective within two-dimensional representational space that is common in emaki picture scrolls and, more generally, highlights how traditional Japanese artistic idioms inform teamLab’s digital works.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Figures

- Preface

- Introduction

- PART I

- PART II

- Conclusion

- Epilogue

- Interview

- Bibliography

- Index

- Back cover