![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE GENIUS OF THE PLAN

By titling their plan for Central Park “Greensward,” a term used to describe a wide-open, grass-covered ground or turf, Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted set the stage to transform a broken, swampy terrain with pockets of settlement into a pastoral oasis for millions of city dwellers. While the park looks and feels like the last remaining parcel of nature left on the island of Manhattan, it was almost entirely man-made. The composed landscape was created through a combination of visionary planning, brilliant engineering, and a massive human effort.

From a masterful drainage system devised by a twenty-four-year-old engineer to the decorative park benches created for the restful enjoyment of those promenading on the Mall, this chapter explores the infrastructure of Central Park. Drawings of features such as the underground technology that was required to prepare the Lake for winter skating; the sunken transverse roads used to carry traffic through the park without intruding on the flow of people, horses, and carriages within the park, not to mention its pastoral views; and the endless charming architectural details and thoughtful designs for more utilitarian additions, underscore the behind-the-scenes thought and labor needed to make the park an artistic masterpiece for the ages.

PARK DRAINAGE

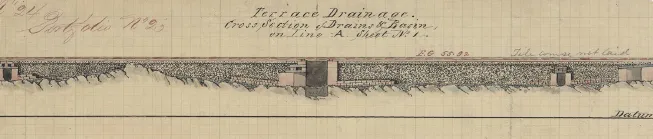

Before construction began, the parkland’s 843 acres of rough and varied terrain contained five major watersheds, with a natural drainage system that flowed out toward the East River. Thanks to the poor quality of its soil and the high embankments—remnants of creating uniform street grades—that surrounded it, many areas were filled with pools of stagnant water. Engineer-in-Chief Egbert Viele, who had undertaken a topographical survey of the site before assuming his position, warned the Board that if the land was not properly drained, it would remain, “a pestilential spot, where rank vegetation and miasmatic odors taint every breath of air.” In addition to health concerns caused by the standing water, drainage was also imperative to maintaining the loose, fertile soil required for the vast amount of planting that would be needed to turn the bleak landscape into the parkland that the city was expecting.

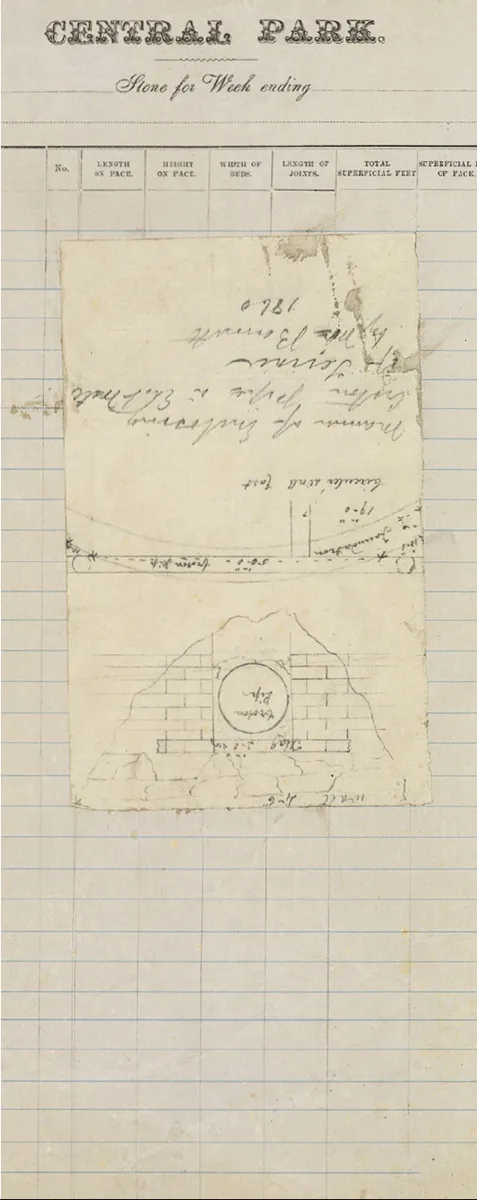

Twenty-four-year-old engineer George E. Waring Jr. was hired to develop and implement a drainage system, a monumental effort that made the park possible. In June of 1858, Waring and a team of four hundred laborers began digging ditches, opening natural streams, and clearing trenches three to four feet deep at forty-foot intervals to install a system of drain tiles—essentially perforated clay pipes that collect water from the surrounding soil. The pipes drew water down into collecting drains, and where several drains met, a silt basin was placed to allow water to pass while removing any foreign materials.

By December 1858, Waring and his team had laid over twenty miles of drain tile, created thirteen basins, and had managed to reroute enough water to fill the twenty-acre Lake to the depth of four feet, in order for it to be ready for the 1859 winter ice-skating season.1 Olmsted reported to the Board in March of that year that “the results of the drainage, thus far, had been satisfactory, many parts of the Park which were impassable swamps before drainage, being now hard and dry. Various pools of standing water have disappeared and from their bottoms thousands of loads of muck, valuable as manure, have been taken for cultivation.”2

Manner of enclosing Croton pipe in east wall of the Terrace, 1860. Pencil on paper pasted on printed letterhead, 13½ × 8¼″.

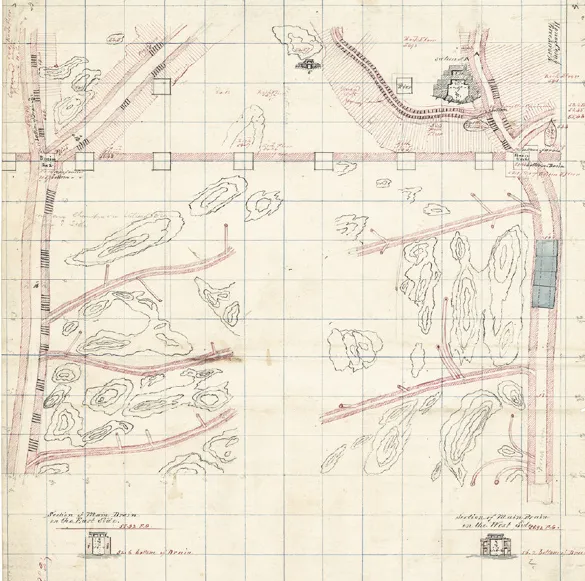

Plan of Terrace drainage, showing drains and basin, 1863. Black and red ink colored washes and pencil on graph paper, 16¼ × 13¼″.

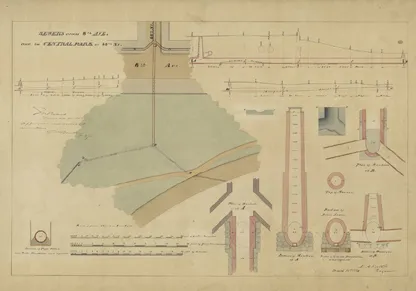

Sewers across Eighth Avenue and in Central Park at Eighty-Eighth Street, 1884. Black and red ink with colored washes on cloth-backed paper, 28¾ × 42″. Approved by engineer Montgomery A. Kellogg, March 8, 1884.

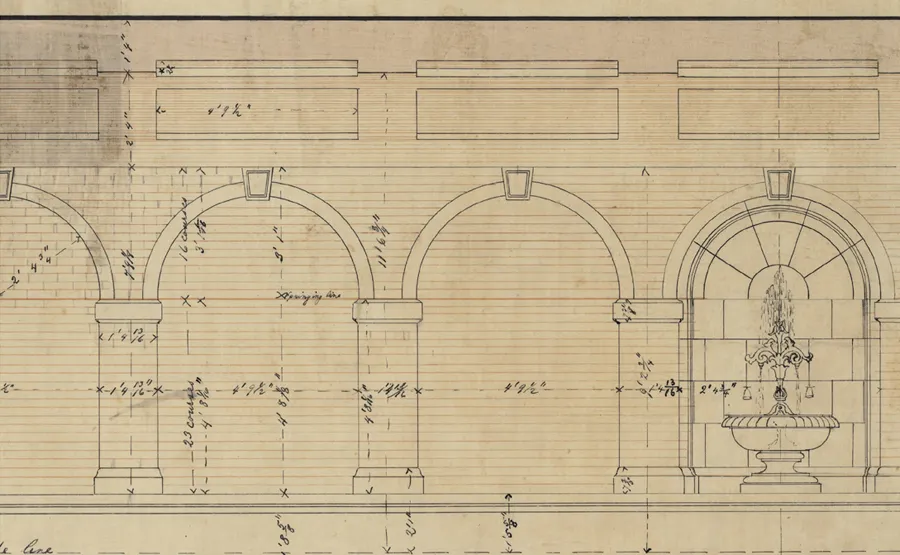

Design of main drains for Terrace and Mall, c. 1863. Black and red ink with colored washes, pencil, and crayon on graph paper, 16¼ × 13¼″.

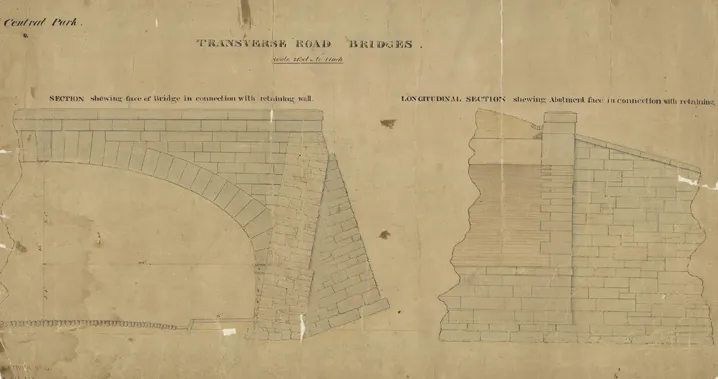

Transverse Road bridge showing the abutments and retaining walls, c. 1859. Black and red ink with colored washes on cloth-backed paper, 19¾ × 34½″.

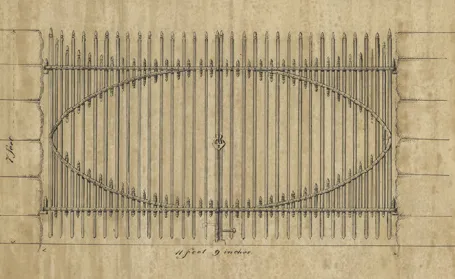

Elevation of a gate for the Transverse Roads, 1863. Black ink and gray wash on linen, 13¼ × 25½″.

TRANSVERSE ROADS

Vaux and Olmsted’s traffic circulation system for Central Park is often considered the genius of their plan. Especially notable were the Transverse Roads (referred to as thoroughfares until 1862), which enabled east-west traffic to pass through the park. Early park biographer Frederick B. Perkins wrote, “so simply and plainly did this device meet the case [of separating the park from crosstown traffic], that it had much weight in the deciding of the Board of Commissioners to adopt the plan which contained it.”3

Even though the majority of New Yorkers lived far south of the park in 1857, the Board of Commissioners recognized that development would move northward and that provision for crosstown traffic would have to be made. Egbert Viele’s rejected plan for the park had included thoroughfares across the park, and the design competition rules specified that at least, “four or more crossings from east to west be made between Fifty-ninth and One Hundred and Sixth Street.” Ironically, shortly after the Greensward plan was selected as the winner, two of the commissioners, August Belmont and Robert J. Dillon, unsuccessfully advocated for eliminating the Transverse Roads, stating that, “there will be little or no such business relations of one side with the other as to require vehicles of traffic to cross the Park.”4

Vaux and Olmsted came up with an ingenious scheme for these Transverse Roads that worked seamlessly to avoid fragmentation of the park. Unlike all of the other designers, who submitted plans showing the required roads at street level, they sank the roads out of sight, which made it possible to keep park visitors safely above the crosstown traffic, which they colorfully portrayed in their proposal as “coal carts and butchers’ carts, dust carts, dung carts” and fire companies “rushing their machines with fantastic zeal at every alarm.”5 The designers intended that the borders of the roads and the wide north-south bridges crossing them be heavily planted in an effort to create an appearance of endless parkland for park visitors.

A precursor to modern-day parkway construction, this bi-level road system was a new, albeit expensive, innovation that required extensive excavation and manpower. While Vaux designed the roads, it was William H. Grant who provided the engineering expertise. Together they developed a forty-foot-wide roadway that included a 6½-foot sidewalk on either side. The retaining walls were faced with Manhattan schist taken from the park, and the bridges were constructed from hard-burnt brick, although one on Transverse Road No. 2 had to be tunneled through the rock formation that made up Vista Rock, the second-highest peak in the park. The Transverse Roads posed an especially difficult drainage challenge, but Grant, working with J. H. Piper, conquered the problem. The roads, made up of a combination of cinder and gravel, were crowned and lined with granite gutters. Both the porous surface of the roadway and the gutters drained into a series of catch basins below the surface. The basins were connected to a storm-water collection area that drained into park waters or, in some cases, directly into the city sewer system.6 Completed between December 1859 and the fall of 1862, the Transverse Roads still provide uninterrupted routes across town without intruding on the...