![]()

ONE

A South American Pacific

FROM THE COLONIAL PERIOD to the nineteenth century, Peru and Chile were part of a globalizing world. Indeed, recent genetic research shows that before the arrival of Europeans in South America, indigenous people in the Americas—probably from what is today northern Peru, Pacific Colombia, and southern Peru and Bolivia—built vessels that transported people and potatoes to the easternmost portion of Oceania.1 Even for those who did not venture into Oceania, the Pacific played a key part in agricultural production through the use of guano, a fertilizer developed from bird excrement and the fish on which the birds preyed.2 During the colonial period, cartographers for the early modern Spanish empire produced representations of the Pacific in an effort to prove that the western Pacific belonged to the Spanish realm.3 With independence from Spain in the early nineteenth century and then the expansion of guano and later nitrate exports, and with the key place of Valparaíso in shipping (especially before the construction of the Suez Canal and the Panama Canal), Peru and Chile became even more connected to the Pacific than before. The Pacific Ocean was a central part of the long history of both Peru and Chile.4

This chapter takes as its starting point these connections to the Pacific world. Importantly, it emphasizes the internationalness of the maritime world, from merchant ships to warships. More specifically, it analyzes the Peruvian and Chilean maritime world in the Pacific from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries. It shows the cosmopolitan nature of ships and port cities along the South American Pacific littoral. These locations bring out the broad connections built through the maritime world, from the Peruvian Andes to Tahiti, Rapa Nui/Easter Island to Manila, and importantly from the Chilean coast to the Peruvian coast. The cosmopolitan nature of the Pacific means that even when the nationality of all people involved in a scenario is not given, much of the shared experience discussed throughout happened in settings within which they probably interacted through living quarters, labor regimes, and port life. Living and working together need not necessarily result in cooperation all of the time, but it does mean that they had to get along well enough for the continued functioning of a ship or the life and commerce of an urban port like Callao. And even when seemingly separate, similar historical processes occurred in both countries’ port cities in more or less the same time period.

The maritime world encompasses numerous aspects. This chapter deals with the quotidian aspects of this world for maritime workers, both at sea and in port. It analyzes the enrollment of workers on ships, reports from foreign diplomats, letters written on board ships, ministerial letters and reports, and the anarchist press to uncover what it meant to work on and around ships. This was a world constructed through contradictions. For some the ocean and work in the maritime industry meant freedom. For Manuel Rojas, a twentieth-century Chilean novelist and anarchist who spent a good portion of his life connected to the maritime world, the sea allowed people to “choose their own destiny” (elegir mi destino), whether that be Panama, Honolulu, or Guayaquil; as opposed to the defined pathways of land, the ocean was “a large path” with “amplitude, solitude, freedom, space, yes, space.”5 On the other hand, many found their way onto ships as unfree laborers alongside contracted workers, both living and breathing under strict hierarchical discipline. These contradictions or paradoxes open up space to examine the complex world within which thousands of people lived, worked, fought, organized, and died.6

SHIP COMPOSITION: MULTINATIONAL CREWS AND THE CASE OF THE AMAZONAS

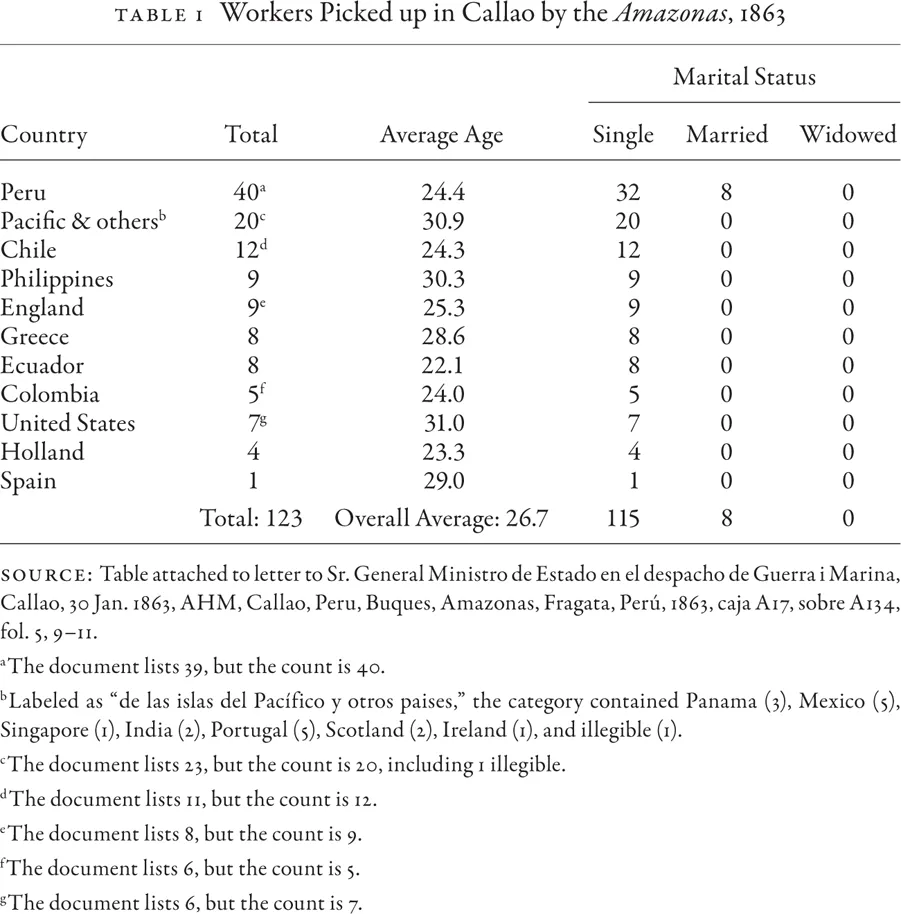

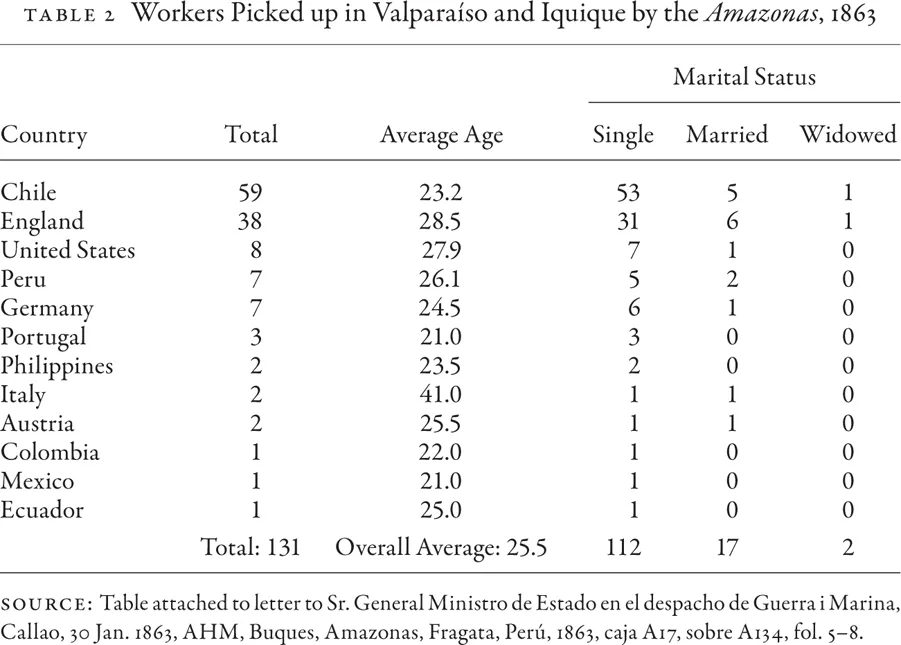

The ships that traversed the various ports of the Pacific flew the flag of only one nation, but their crews were anything but nationally homogenous. The crew of the Peruvian frigate Amazonas in the mid-nineteenth century reflects the multinational nature of crews in that era. Built in London from 1850 to 1852 in the Wigram shipyard, the Amazonas displaced 1,320 tons, measured 200 feet in length, and carried around 360 crew members.7 Departing from the Peruvian port of Callao on October 25, 1856, the Amazonas began a journey to circumnavigate the world. The trip took the ship across the Pacific ocean to Hong Kong, Calcutta (where some thirty-nine crewmembers died from cholera), Saint Helena Island in the African Atlantic (where they visited the tomb of Bonaparte), London, Rio de Janeiro, Talcahuano (Chile), Arica (Peru), and finally back to Callao on May 28, 1858.8 In 1863 the Amazonas made stops in Valparaíso, Iquique (at this point still a part of Peru), and Callao to recruit maritime workers. Although the records from these stops do not show the entire crew, they do cover a decent amount of the composition of the ship, as 123 new workers joined in Callao and 131 in Valparaíso and Iquique, or 34 and 36 percent, respectively, of the approximately 360 total crew members on the ship. As seen in tables 1 and 2, a plurality of the new crew members in Callao came from Peru: 40 of 123 identified as Peruvian, meaning that over two-thirds of those who boarded in Callao were not Peruvian. In Iquique, a Peruvian port city that would become Chilean after the War of the Pacific, all 11 of the new crew members were foreign born (8 from England, 3 from the United States). The new crew members who were picked up in Valparaíso leaned heavily Chilean (59), followed by British (30), after which the total numbers decline significantly, but the nationalities represented vary from the United States to the Philippines to Germany. The second largest group to board in Callao were Chileans, followed by Filipinos and British, and a mix of Mexicans, Portuguese, and South Asians. The multinational crew of the Amazonas of the 1860s meant that people worked across differences of language and national background. Maritime crews must have learned ways of working on a ship with people who may not have spoken their language. The crew most likely learned about other cultures on board, too. Even if some of these Chilean and Peruvian crew members never made a trip away from the South American Pacific littoral, they experienced a part of South and Southeast Asia and Europe through living and working with crew members from these locations. The national origins of those picked up in Callao, Iquique, and Valparaíso also reveals that the South American Pacific strongly leaned toward the Pacific Rim and Europe, without a single mention of a person from the Latin American Atlantic. This was a ship with a multinational crew, but one that pulled from specific places: the Pacific Rim and Europe. Significantly, Peruvians and Chileans worked together in tight quarters on board ships like the Amazonas. The cosmopolitan nature of crews remained consistent over time, as well. In a case from 1918, for instance, when the sailboat San Joaquín picked up crew members from the Peruvian sailboat Helvecia after it sank, the workers hailed from Peru, Chile, Russia, Mexico, Costa Rica, Colombia, and Spain.9

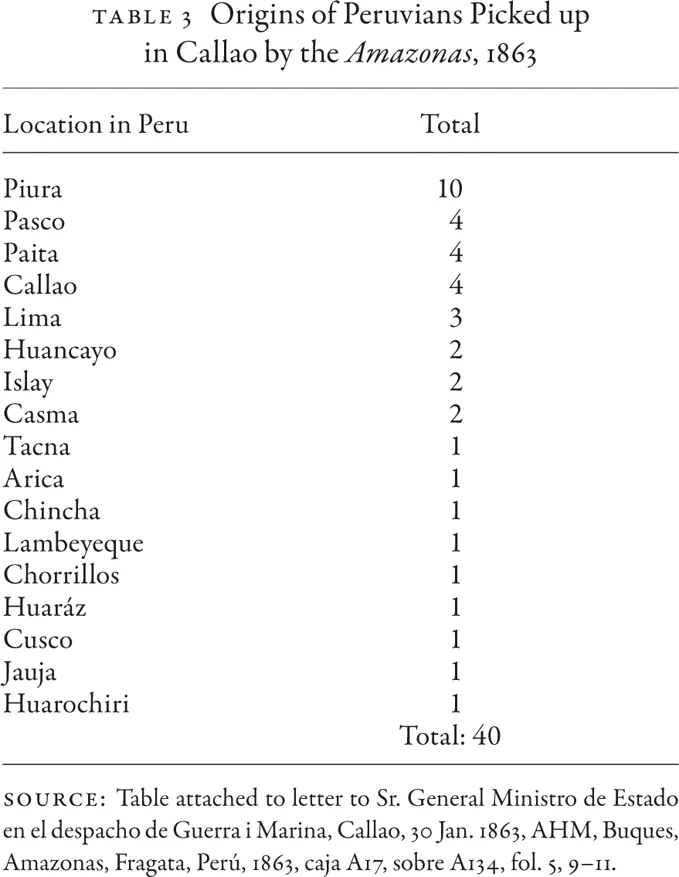

Differences existed within the same national group of workers, and it may have been the first time some had met a fellow countryman from a specific location. When the Amazonas picked up Peruvians in Callao in 1863, the keeper of the ship’s manifest noted their origin from within Peru (see table 3). Of the forty Peruvians, ten came from the far northern city of Piura near the port of Paita, with others coming from places such as Islay in the south and Arica in the far south, as well as a few hailing from the Andes (Huancayo, Jauja, Huaráz, and Cusco). This multiregional Peruvian crew on the Amazonas was not unique. After a failed rebellion on the steamship Lerzundi in 1865, the Peruvian state took note of where the people sentenced to prison or forced work came from, as well as their physical appearance and scars. In some cases, the exact location is not clear, as they are listed as being from “Peru.” Others, though, were identified as being from Ayacucho, Arequipa, Cuzco, Jauja, Ica, and Huaura. They were also from various racial backgrounds, if we can believe the classifications assigned to them: seven of them are listed as indigenous, two as mestizos, one pardo, one white, one mulato, and one zambo.10 In other words, these were ships populated by people from around the world, and even when workers came from the same country, their origin within that country varied. In another case, when Peruvian workers, and many others, died or were saved after ships sank in a windstorm in Valparaíso in 1903, the list of birthplaces shows the continuance of the broad geographic range of maritime workers from Peru. Many came from Callao, but others were born in Quisque (in the Andes between the coast and Huancayo), Chiclayo, Piura, Arica, Paita, Andaray, and Chira.11

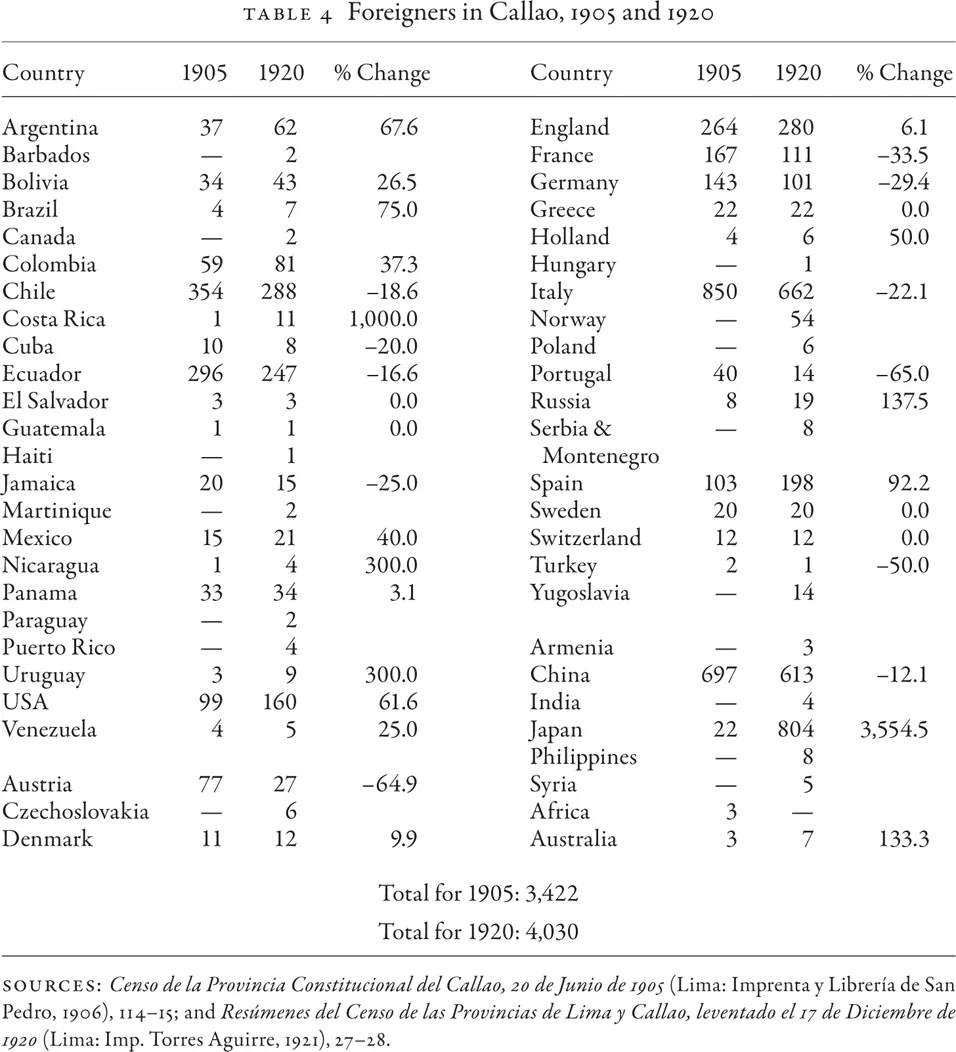

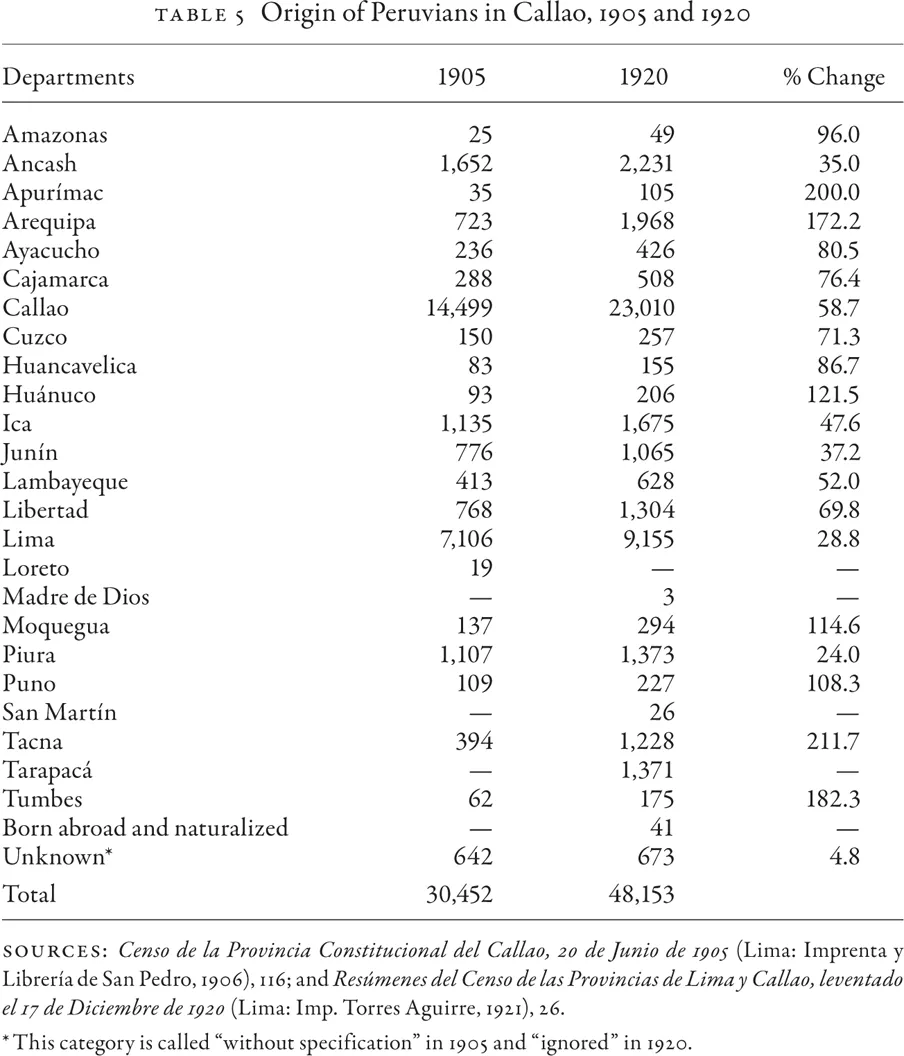

When maritime workers arrived at port, they also stepped into cosmopolitan cities. The port of Callao in the early twentieth century provides such an example. Despite inherent problems with census taking at the time—even the census administrators in 1920 proposed error coefficients ranging from 1 to 6 percent depending on location—censuses do offer some of the only quantitative data on population.12 Between 1876 and 1920 the port added fewer than 20,000 inhabitants, rising from just under 35,000 to a little under 53,000, with a dip of around 5,500 at the end of the 1890s. According to the 1905 census, of the 33,879 residents of Callao, 3,449, or 10.18 percent, were foreigners. Of the Peruvian population in Callao, women were a slight majority (15,941 to 14,489), while the foreigner population was overwhelmingly male (2,503 to 946). Peruvian residents of white (13,122) and mestizo (13,338) background made up most of the city, with indigenous (5,276), Afro-Peruvian (1,317), Asians (719), and those without data (107) making up the rest.13 The low percentage of Afro-Peruvians and Africans was a change from earlier periods, when Callao could easily be described as a port of the Black Pacific.14 Non-Peruvians came from a number of places. Men and women from across the Americas had made their way to Callao, including 354 Chileans and 296 Ecuadorians, the two greatest numbers from the Americas (see table 4). Europeans also found a home in Callao, with the largest numbers made up by Italians (850) and the English (257). Of the 719 Asians counted by the census, 697 were Chinese and 22 Japanese.15 By 1920 the percentage of foreigners in Callao had dropped slightly from its 1905 level, but there were still 4,032 foreigners in a population of 48,226 (8.36%). Of those from the Americas, Chileans (288) and Ecuadorians (247) still outweighed their counterparts, as did the British (280) and Italians (662) when it came to Europeans. Between 1905 and 1920, the category of Asian expanded to include Armenia, the Philippines, India, and Syria, and the number of Japanese (804) exceeded the number of Chinese (613). Both the 1905 and 1920 censuses also detail the birthplace of Peruvians in Callao. In both 1905 and 1920 the vast majority of Peruvians were local, from either Callao (14,499 and 23,010) or Lima (7,106 and 9,155) (see table 5). The rest spanned nearly the entirety of Peru and areas in dispute with Chile. Several departments registered numbers exceeding 1,000, such as Ancash, Arequipa, Ica, Piura, Tarapacá, La Libertad, and Junín. Hundreds of residents had been born in Ayacucho, Cajamarca, and Lambayeque, as well. And some came from departments in the Amazon jungle region, such as Amazonas, San Martín, and Madre de Dios.16 As a whole, more than 15,000 Peruvians in Callao were born outside of Callao and Lima. While these figures might not be completely accurate, they do show both the high number of foreigners living in Callao as well as the large numbers of Peruvians from other parts of the country living and working in the city. In other words, the crews working ships and the people living and laboring in port cities were both international and intranational.

In some cases, despite years of working in multinational crews, maritime workers found it difficult to find work due to their limited language skills. In 1913 the Chilean Ministry of Foreign Relations relayed to Santiago dismaying news on Chilean maritime workers in Europe. While the Chileans had worked alongside people speaking various languages and made it across the Atlantic with them, some ships would not hire them because many could not speak English, French, or German. Ship captains also had to contract for Chilean maritime workers through the Chilean consulate, an added burden many wanted to avoid entirely.17 Even if they did not speak numerous languages fluently, many workers were able to transcend language limitations. Many on the Amazonas in 1863 did not speak Spanish, for instance, yet they did not have any trouble working together in a disciplined and orderly fashion.18 Some also knew enough of another language to get by, to exchange the information necessary to continue living their daily lives. Ships and ports were, after all, cosmopolitan places. When a vagabond (vagabundo) in a Chilean port heard a marine ask him if he was hungry in English, he understood the question and knew how to respond in English. “A tramp ...