![]()

1.

The Story of Carbon: The Birth of the Universe, of Carbon, and of Life

We drink from wells we did not dig,

we are warmed by fires we did not build.

—Deuteronomy

With this book we present a solution, one among many that can start to reverse climate disruption and begin climate healing. First, however, we need to take a careful look at the problem we hope to solve, which starts with a look in the rearview mirror: How did we get here?

In the introduction we portrayed a short history of culture and architecture near San Francisco and Toronto, for just the past few hundred years. Now we vastly expand our time and spatial scales, starting with a whirlwind tour of the story of the Universe, within which is the story of carbon, within which is the story of us, the human beings, as science gets it so far.

13.7 Billion Years Ago

The Big Bang (BB) banged and is still banging, right here, right now, right where you’re sitting. Modern physicists devote their careers to trying to puzzle out just what that “bang” was, in which the entire known universe began from one point in space and time. What happened in the first second? The first microsecond, or nanosecond? What was there before that? Has this happened before? When reading modern cosmology, it can seem like this Big Thing happened, like Star Wars, long ago and far away. It certainly did begin a long time ago—14 billion years is a bit beyond most people’s comprehension—yet you are in and part of it. Everything you can see or love or hate or build or build with is part of the Big Bang, even if it’s not quite so loud and bright anymore.

BB + 380,000 or So Years

Things have finally cooled and depressurized enough for the first physical matter, the elements hydrogen and helium, to appear and begin coalescing into ever-denser clouds of gas until—

BB +200 or So Million Years

The first stars appear, beginning to forge the heavier elements in their cores via nuclear fusion, eventually to go supernova (explode), scattering those heavier elements into space to then set to work coalescing into more clouds until—

BB + 2 Billion Years (12 or So Billion Years Ago)

The next generations of stars start to appear (everything still exploding outward in every direction from the Big Bang), in many cases those new stars form with orbiting planets and moons, leading in at least one case to—

4.5 Billion Years Ago

Our Earth, Sun, and solar system are formed. After a half billion or so formative years of grinding, sloshing, and fuss, the Earth settles down a bit with a more or less stable world of continents, oceans, and atmosphere. And then the fun begins with the first appearance of—

About 4 Billion Years Ago

Life! Wow, life! As inexplicable to us as the original Big Bang itself, life started with very, very simple anaerobic microorganisms, developing and evolving over eons to fabulous complexity recurring several times over as six mass extinctions reset the stage (for various reasons, though none until now due to the effects of any single species). Climate changes, endless tectonic rearrangement of land masses, the wobbling of the poles, and many other effects keep things moving and changing while the impetus to live and evolve hums unceasingly in every living thing.

About a Quarter of a Billion Years Ago

Before we get to the emergence of human beings, let’s note a few among so many interesting periods in the geologic record, the ones that stand out in this Story of Carbon: the ones that gave us fossil fuels. The Carboniferous was a geologic period from the end of the Devonian, 360 million years ago (mya) to the beginning of the Permian 300 mya. The name Carboniferous means “coal-bearing,” and that’s what it became: a lush, thickly forested Earth that over time became beds of coal whose use would change the world. Oil, or more properly petroleum, has a more varied geologic provenance: decayed algae and plant life coming a bit from the Paleozoic (541 to 252 mya) and the Cenozoic (65 mya), but mostly from the Mesozoic (252 to 66 mya). So hundreds of millions of years ago the stage was set for a goofy band of primates to come along and discover these reservoirs of superconcentrated energy—and immediately complete their takeover of the planet.

About 3 Million Years Ago

The seminal genus Homo appears in Africa (we are all African!), moving and evolving north up the Nile River valley and the Arabian Sea to scatter, eventually, all over the world into multiple predecessors and versions of early Homo sapiens.

About 300,000 Years Ago

Anatomically modern Homo sapiens appear in many forms and places, as we can infer from the fossil record. Hard evidence of our arrival comes from as much as forty thousand years ago, most famously the cave paintings such as those of Chauvet and Lascaux in France that solidly announce people like us in their social organization and cognitive ability. This was the emergence of a particular version of Homo sapiens (sometimes but not always called Homo sapiens sapiens) who were both fruitful and dominant, spreading all over the world and eliminating competing versions of Homo sapiens. These were human beings who, if given the chance, could learn to successfully fit into your world, or vice versa. They could think, they could feel, they could reason, they could imagine. More about that imagination thing in a moment.

10,000 or So Years Ago

The Agricultural Revolution: We learned to grow and manage plants and animals for food. Generally thought to have first started in the Fertile Crescent of southwest Asia (modern Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Iraq), agriculture also had other beginnings in Asia and the Americas. The Agricultural Revolution arguably spawned many, many other things that changed us, such as political states, mass religion, and the beginning of architecture: durable buildings, cities, and infrastructure.

250 Years Ago

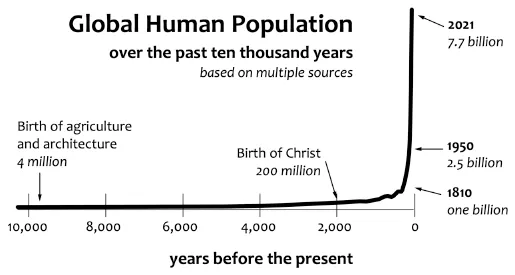

The British, like many others around the world who had found coal, had been burning it (or its undercooked cousin, peat) for centuries to warm their homes and schools. But they could only mine the coal down to the water table, not far below the surface, because going deeper meant flooded mines. Steam-powered pumps were already around, but Scottish inventor James Watt (from whom we get the eponymous unit of electrical power) devised in 1776 a dramatic improvement that could not only pump water more effectively but also be put to use driving all sorts of other mechanisms such as trains, tractors, and looms. That moment is generally credited with launching the Industrial Revolution and also accelerated humanity up a hockey stick population surge that still roars on today (figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1. Global population since the dawn of agriculture.

Today

Here you are, the stardust kid! Here we all are, and our kin: giraffes, turtles, kelp forests, red winter wheat, the mold on the cheese, and every other living thing. We who live are a carbon family, tied by our common ancestry. Our bodies are 18 percent carbon, most of the rest being hydrogen and oxygen (as water) sprinkled with a number of trace elements. We are the carbon-based human beings in the billions who, like the sorcerer’s apprentice, have discovered a magic that now runs out of control, threatening to destroy us and so much around us.

But Wait! There’s More!

In our rough and simplified version, this is the Story of Carbon to the present moment—the creation story as given by science and the scientific method.

Here we can note fun correlations between scientific fact (or, anyway, agreed-upon inference) and the creation myths that permeate human culture and history. Hydrogen and carbon, for example, can be imagined as Adam and Eve, progenitors of the family of life (and fundamental to a circular economy; more on those two crucial elements in chapter 11, “Policy and Governance”). Or the Big Bang as Vimalakirti’s one small room of emptiness that easily holds tens of thousands of Buddhas and radiant beings, all on resplendent thrones, or the Hindu cycle of yugas, immense cycles of time far, far beyond human comprehension. Or old Coyote—dirty, tricky, stinky Coyote—who grabbed a nice, neat blanket full of stars and shook it, making the Milky Way.

And so on. We note the correlations and invite you to draw your own connections as you like. But don’t think, dear reader, that this is an idle sidebar exercise; it is foundational to this book and to the future of humanity. If you—if we—don’t look at and recognize the beliefs and myths that we hold, that we swim in like a fish in the sea, then we’re running blind, and that can be quite dangerous.

Legends, myths, gods and religions appeared for the first time with the Cognitive Revolution. . . . None of these things exists outside the stories that people invent and tell one another. There are no gods in the universe, no nations, no money, no human rights, no laws, and no justice outside the common imagination of human beings. . . . Fiction has enabled us not merely to imagine things, but to do so collectively. We can weave common myths such as the biblical creation story, the Dreamtime myths of Aboriginal Australians, and the nationalist myths of modern states. Such myths give Sapiens the unprecedented ability to cooperate flexibly in large numbers. . . .

Wolves and chimpanzees cooperate far more flexibly than ants, but they can do so only with small numbers of other individuals that they know intimately. Sapiens can cooperate in extremely flexible ways with countless numbers of strangers. That’s why Sapiens rule the world.

—Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens

When we share the same myth, the same creation stories and world narratives, we thrive and conquer the world. When we don’t, we often fight. Not always, but often enough, and our tendency to be vicious and combative is usually rooted in differing myths. Consider, just for a few examples, the Crusades of the Middle Ages, the rape of Nanjing, the attack on the World Trade Center on 9/11, or the attack on the U.S. Capitol by QAnon adherents on January 6, 2021. All made by fervent believers more than certain that they were doing the Right Thing, usually for “God” in one way or another. We act out our creation stories and cover the land with misery and blood. We started this book with the assertion that human beings can be very cool, but must also solemnly note that all too often we are emphatically not.

Even worse, many of our mythic narratives don’t jibe well with science and amount to an ongoing argument with reality. There is a very old cartoon depicting two South Pacific Islanders standing on a beach and looking out across the ocean at the smoking volcano on the distant horizon. One of them says, “Well, either the fire god Kam’aah’aa is angry because we haven’t sacrificed a virgin after the last eclipse, or else a mass of nonviscous and superheated magma has forced its way through a tectonic fracture in the crustal plate.” A funny joke, yes, but not so funny, if they go with the first theory, for some young village girl and her family. That’s the trouble with arguing with reality: Someone always gets hurt.

We’ve been acting out wacky mythic things for a very long time, of course, but at this particular moment in the Story of Carbon, that tendency is hugely amplified for several reasons.

We Are Many

In a very, very short time we have exploded in population: Just in my lifetime, the global population has more than tripled. We’re driving a mass extinction by our commandeering of territory and consumption of resources, and our presence on Earth is felt by every creature. From the deepest ocean to the highest peaks, from the poles to deep in the Amazon rainforest, we can be felt, even if not seen, smelled, and heard outright.

We Are Connected

Technology links us together, for both better and worse. Jet travel quickly spread the COVID pandemic all over the world, and phone and video connections, just a science fiction dream until a generation ago, are now common.

We Have a New Kind of Problem

COVID appears to have been the first truly global experience, the first global problem. But of course it’s not: Our cumulative effect on each other and the rest of life (tragically externalized as “the environment”), especially as disruption to the climate, has been a visible and growing global problem for decades.

And We Most Definitely Do Not Share the Same Creation Myth

This is much more than subscribing to different religions, problematic as that so often is. My creation myth tells me who I am, who my tribe or community is, and likewise defines my nation and the world. It tells me who are the Good Guys and who are the Bad Guys (you can’t have one without the other). I couldn’t possibly fathom the mindset of my own great, great, great, great grandfather, about whom I know almost nothing, and neither does my worldview much correlate with his, or that of a North Korean farmer, a Nepali government bureaucrat, an Amazon tribeswoman, or plenty of people in my own country. Add a few dozen examples of your own; we all occupy different worlds, almost but not quite literally, with completely different Good Guys and Bad Guys.

What could possibly go wrong?

In today’s politics, I find that a lot of transient and trivial issues of the moment dominate the political imagination through the media, and in doing so, they diminish and marginalize these bigger issues we should be thinking about. . . . Nothing I see today indicates that people are taking these problems as seriously as we need to. We need leaders who, informed by science, adopt a common-sense practicality. Let’s understand our stories, but le...