![]()

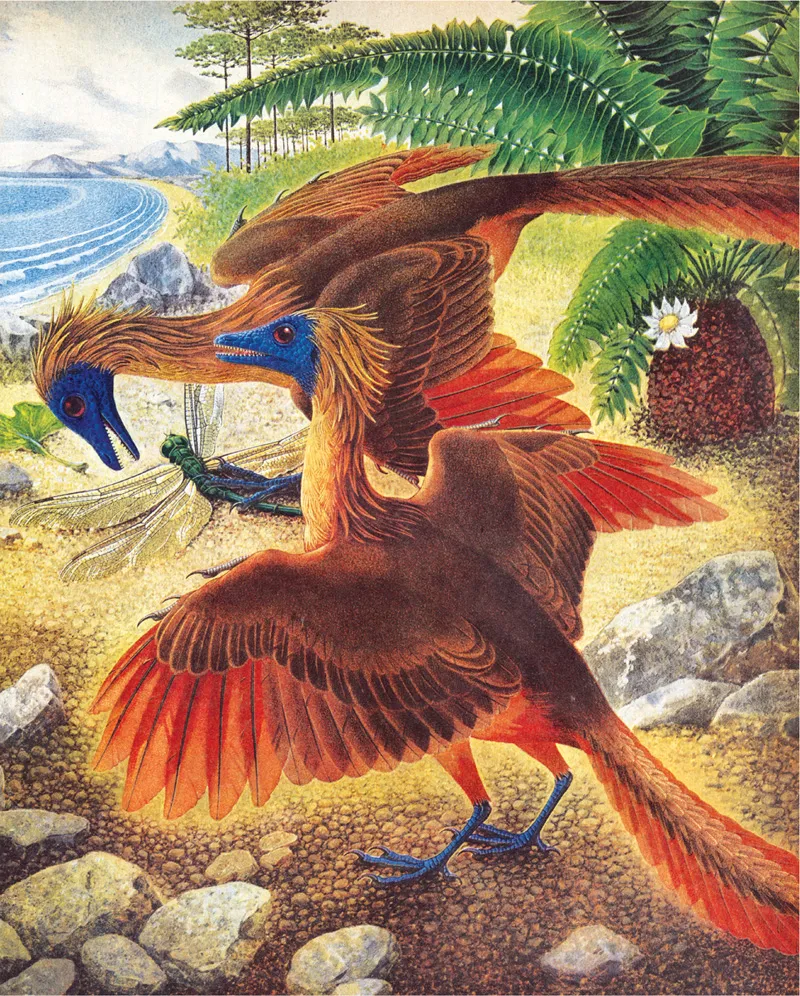

A pair of Archaeopteryx lithographica. Painting by Rudolf Freund for an article in LIFE magazine on evolution (Barnett 1959). In 1959 nothing was known about the colors of plumages and bare parts of fossil birds, so Freund was guessing (probably incorrectly, as it turns out).

CHAPTER 1

Yesterday’s Birds

The road from Reptiles to Birds is by way of Dinosauria to the Ratitae.

—THOMAS HENRY HUXLEY, IN A LETTER TO ERNST HAECKEL ON 21 JANUARY 18681

THE TERRIBLE CLAW

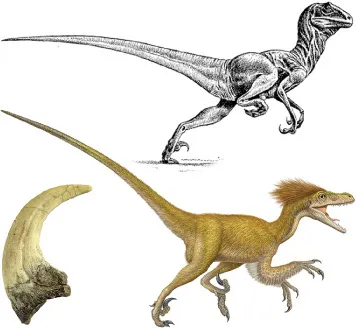

LATE ONE HOT AUGUST EVENING IN 1964, near Bridger, Montana, the paleontologist John Ostrom and his assistant, Greg Meyer, made a discovery that revolutionized the study of ancient birds. Toward the end of a hard day in the field, they spotted, in the slanted light, some claws and bones protruding from the reddish-brown soil. Scrambling to the spot, they began digging with the only tools they had at hand—a jackknife, a small paintbrush, and a whisk broom. Rapidly running out of natural light, they marked the location so they could resume work the next morning. Given the fossil’s sickle-like claws, Ostrom was convinced this was a carnivorous dinosaur: “I was almost certain, although still wary, that we had discovered something totally new.”2 And they had, as the subsequent week of excavation revealed—a specimen considered by some3 to be the most important dinosaur discovery of the mid-twentieth century, an animal Ostrom called Deinonychus, “the terrible claw.” This was a seventy-kilogram bipedal runner with sharp claws on all four feet and an especially out-sized retractable claw on the second toe of each hindlimb. Deinonychus was a killing machine, and its study revolutionized our understanding of how dinosaurs lived and breathed and how birds evolved. Deinonychus was a member of the Dromaeosauridae, a family of theropod dinosaurs—including Velociraptor, made famous by the movie Jurassic Park—that proliferated in the Cretaceous.

Like so many others who influenced ornithology in the early twentieth century, Ostrom started out studying medicine. Growing up in Schenectady, New York, he began his premed studies there at Union College in the late 1940s. Prophetically, one of his course requirements was to study evolution, so—keen student that he was—he started to read the course text, Simpson’s (1949) The Meaning of Evolution, the night before the first lecture. Enthralled, he spent the night reading, then wrote to the author, the eminent paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson, to say how excited he had been by what he had read. Much to Ostrom’s surprise and delight, Simpson answered right away, inviting Ostrom to come and study the paleontology of mammals with him at Columbia University in New York City. To the chagrin of his parents, Ostrom abandoned his medical studies and moved to the big city, in 1951, to begin a PhD on the paleontology of reptilian dinosaurs, in the end working with a leading dinosaur specialist, Edwin H. Colbert, rather than Simpson. Six years after obtaining his PhD, Yale hired Ostrom as their curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Peabody Museum, a post held a century earlier by one of the great American paleontologists, Othniel Charles Marsh.

Marsh held the first chair of paleontology at Yale, a post created especially for him in 1866. Ever the entrepreneur, he persuaded his wealthy uncle, George Peabody, to donate funds4 to establish a museum at Yale so Marsh would have a place to store and display his fossil discoveries. And discover he did—in twenty years of exploration he and his crew found more than a thousand new species of fossil animals, including eighty new dinosaurs,5 the first pterosaurs from North America,6 and a new group of fossil birds, with teeth, which he called the “Odontornithes.” Marsh’s “Odontornithes,” as presented in his 1880 monograph, included Hesperornis regalis (“the royal bird of the west”) and Ichthyornis (“fish bird”), both of which he had described for science.7 These new birds were related to Archaeopteryx—one of the most famous fossils ever found—and all three of these early birds had teeth, suggesting to Marsh that birds had descended from the toothed reptiles, especially the dinosaurs. Charles Darwin was thrilled: “Your work on these old birds, and on the many fossil animals of N. America, has afforded the best support to the theory of evolution, which has appeared within the last 20 years.”8

Deinonychus antirrhopus was discovered by John Ostrom in 1965. This species was originally depicted as naked (top), but recent evidence suggests that it was covered with “dino-fuzz” as shown here (bottom). A fossil of the sharp hind “killing” claw is also shown (bottom left).

It was not until Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope (from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia) began exploring the western United States in the 1870s that the American badlands began to relinquish their biological secrets.9 Cope and Marsh were both brilliant scientists who laid the foundations of modern paleontology. They are probably most famous, though, for their lifelong feud—aptly called the “Bone Wars”—involving intrigue, chicanery, and insanely intense competition to be first, best, and most famous at everything they attempted, and to have the biggest and most significant collections of discovered-in-America fossils at their home institutions. As we shall see, controversy is a hallmark of paleontology, even today, but the scope, intensity, and nature of the Bone Wars belongs among the great tales of the Wild West, albeit in the name of science. John Ostrom also generated considerable controversy, which continues to this day (2013).

Unlike most of his paleontological predecessors and contemporaries, Ostrom thought about dinosaurs, like Deinonychus, as living, breathing animals, not just as a jumble of bonelike rock embedded in a geological stratum. Even his own PhD supervisor, Colbert, considered them to be “sad, slow, stupid creatures that deserved to be extinct.”10 By focusing on how these animals once lived and evolved—including consideration of their behavior, physiology, development, and ecology—Ostrom’s approach revolutionized paleontology. Ostrom reasoned that Deinonychus must have walked on its hind legs—as its forelimbs were built for killing, not walking—and its posture (based on bone and joint reconstruction) was likely upright, bipedal. As a predator, Deinonychus would have pounced on its victims, ripping them open with its razor-sharp claws, possibly using the extra-large claws on its back feet to hold its prey down (Fowler et al. 2011), much in the manner of raptorial birds today. Contrary to the standard (albeit Victorian) image of dinosaurs as enormous, plodding, dim-witted beasts, Deinonychus was a relatively small—3.4 meters (11 feet) long—nimble predator with an active lifestyle, and was almost certainly warm blooded.

Just about everything that Ostrom suggested about Deinonychus was unorthodox: here was a dinosaur more like a small ostrich than the lumbering giants usually depicted in books. Could it be that birds and dinosaurs were more closely related than had previously been thought? To explore this possibility, Ostrom needed to reexamine both the oldest known fossil bird, Archaeopteryx, to learn about the origins of birds, and the pterosaurs, to learn about the origins of flight in the vertebrate animals.

ARCHAEOPTERYX

When Ostrom began his study of Archaeopteryx in 1970, only four specimens were known—a lone feather and three partial skeletons—arguably the most important, valuable, famous, and beautiful fossil animal ever found. Ostrom traveled to Europe to study the original specimens kept in London, Berlin, and Maxburg (Germany), and to visit the vast Solnhofen quarries, where the only Archaeopteryx specimens ever have been found. To put Archaeopteryx into context of the evolution of both reptiles and flight, Ostrom also went to the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, Netherlands, where some of the world’s most complete pterosaur fossils were housed. Pterosaurs—the group that includes the pterodactyls—were flying reptiles, contemporaries of Archaeopteryx but not closely related to birds. However, they had several anatomical adaptations for flight that Ostrom wanted to study in detail. With its neoclassic architecture, the Teylers Museum was (and is) a lovely place to work. At the time Ostrom was working, there was no artificial lighting in the galleries, so the museum had to close earlier in winter when the sun set. It was here in the setting sun that Ostrom made one of his greatest discoveries.

Ostrom was examining the type specimen of a pterodactyl called Pterodactylus crassipes; yet as he looked over the rock he knew that something was not right. As an expert, he could see that this was no pterosaur. He took it to the window for a clearer view, and the slanting, natural light picked out very faint—but very clear—impressions of feathers. It was an Archaeopteryx, mislabeled ever since its discovery in 1855,11 even earlier than the “first” specimen known, and hidden in plain view for more than a century. Ostrom was beside himself, torn between keeping his discovery a secret, lest the museum curator stop his examination, and announcing that the museum actually had this most valuable of specimens. Integrity triumphed, but as Ostrom feared might happen, the curator whisked the specimen away. Ostrom’s immediate reaction—“You blew it, John, you blew it”—was short lived, as the curator soon returned with the specimen in a battered shoebox, saying: “Here, here, Professor Ostrom, you have made the Teylers Museum famous.”12 Even better, he was allowed to borrow the fossil for detailed examination in his own lab. Ostrom was thrilled, but nervous to be carrying such a valuable specimen. He insured the fossil for one million dollars as a precaution, and flew back to Yale with the box on his lap the whole way.

To put Ostrom’s work in perspective, we need to go back more than a century to the first reported discovery of an Archaeopteryx fossil. The year was 1861, only two years after the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species—an amazing coincidence, really, as Darwin had been plagued by the absence of transitional forms, writing: “Why then is not every geological formation and every stratum full of such intermediate links? Geology assuredly does not reveal any such finely graduated organic chain; and this, perhaps, is the most obvious and gravest objection which can be argued against my theory. The explanation lies, as I believe, in the extreme imperfection of the geological record.”13 Darwin noted that many key animal groups were missing from the rather limited fossil record that had been documented by the middle of the nineteenth century. By 1859 a few dinosaur fossils had been found, named, and debated, and there were thousands of fossil invertebrates from around the world, but no obvious intermediates between some of the major, and clearly related, present-day animals, like birds and reptiles. There will always be gaps in the fossil record, but the big ones fuel scientific hypotheses and are grist for the creationist, antievolution mills.

How fortunate, then, that one of the most interesting and useful “transitional forms” ever found should be discovered so soon after Darwin had highlighted the issue of gaps in the fossil record. Here was a fossil with a combination of traits, both reptilian (a long bony tail) and avian (feathers), clearly indicating that it was an intermediate form between birds and reptiles. Here was the best candidate so far for the title of “first bird.”

The British Museum of Natural History (BMNH) in London bought the specimen14 for the then princely sum of £450 in 1862, equivalent to about $55,000 in today’s dollars. The BMNH purchase was especially significant because the leading dinosaur expert of the day—Richard Owen, the man who coined the term “dinosaur”—was curator of paleontology there, and he was keen to make a detailed study15 of what he immediately recognized to be an important specimen. Owen was a brilliant man, but he was also nasty, incredibly ambitious, politically connected, very influential—and very much opposed to Darwin’s new ideas. Here was his chance to show Darwin wrong. His analysis of Archaeopteryx, published in 1863, proclaimed the fossil “unequivocally to be a Bird,”16 and not a transitional form at all. Owen even renamed the species, unnecessarily, as Archaeopteryx macrura, on the (shaky) grounds that it was likely a different species from the fossil feather that had been found in those same beds just a few months earlier, and that lithographica was a poor species name anyway. Or was he trying to snatch some glory as the naming authority17 of this outstanding species?

A cast of the Berlin specimen of Archaeopteryx lithographica, discovered in 1874/75. This is the most complete specimen found so far, and the first with a complete head.

Owen was at odds with many people, one of whom was Darwin’s great friend, Thomas Henry Huxley. In contrast with Owen, whose attempts at public discourse were often both awkward and malicious, Huxley was an articulate, charming raconteur (Desmond and Moore 1991). Huxley had read Owen’s account of Archaeopteryx, and noticing Owen’s errors, may have seen this as an opportunity to embarrass the man who so opposed Darwin’s views. To put the record straight, Huxley embarked on his own careful study of the specimen, completing and publishing his analysis in 1868, “which in part intended to rectify certain errors which appear to me to be contained in the description of the fossil” by Owen.18 Among other things, Owen had mistaken both the left leg for the right and the dorsal for the ventral side, misidentified the right scapula, and had misoriented the furcula (wishbone) and the vertebral column. Huxley’s account made Owen look sloppy and foolish. Even though this first specimen had no head, Huxley (1868a) speculated, correctly as it turns out, that Archaeopteryx would have teeth. Owen, on the other hand, was sure that Archaeopteryx would have a beak so it could...