- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching and Christian Imagination

About this book

This book offers an energizing Christian vision for the art of teaching. The authors — experienced teachers themselves — encourage teacher-readers to reanimate their work by imagining it differently. David Smith and Susan Felch, along with Barbara Carvill, Kurt Schaefer, Timothy Steele, and John Witvliet, creatively use three metaphors — journeys and pilgrimages, gardens and wilderness, buildings and walls — to illuminate a fresh vision of teaching and learning. Stretching beyond familiar clichés, they infuse these metaphors with rich biblical echoes and theological resonances that will inform and inspire Christian teachers everywhere.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

Journeys and Pilgrimages

Setting Our Feet on the Road

THE FIRST OF OUR THREE chosen metaphors involves journeying, and more specifically pilgrimage. The notion that life is a journey is regular fodder for sentimental greeting cards; in classrooms we too get stuck, press forward, are left behind, and reach finish lines. Clichés these may be, but they offer tracks for our thoughts. Sometimes it is not the fresh and striking metaphors, but the images that have become our contact lenses — images habitually looked through rather than looked at — that guide our thinking and doing.

Journeys are all about movement, departures, and arrivals. Thinking of learning in terms of journeys encourages us to imagine learning as taking us away from our origins into new lands, requiring us to let go of some cherished attachments and embrace the new experiences and the new sense of self that arise along the way. Travel images conjure up questions about pace (forced march? mad dash? refreshing stroll?), and about how long to linger in a given spot. Plans for learning become maps and progress reports; we find ourselves looking forward to crossing thresholds and reaching milestones and destinations. Journey-talk raises questions of where we begin, what direction we choose, which maps we will trust, and what wonders, dangers, and distractions might lie along the way. It may also nudge us to think in terms of traveling companions and needed encouragement.

In this part of the book we will explore what happens when we start to think about our educational journeys in a less clichéd manner as pilgrimages. How might it change our approach to teaching if instead of planning learning as though each week were an identical container to be filled with content, we began to think about the rhythms of a journey together? We begin where every journey begins: with the challenge of taking the first step. Pilgrimage is not automatic. In fact, we begin with an image of learning as a prevention of travel, as an enterprise that pins the learner firmly to the ground and makes sure that things stay put.

PINNED TO THE GROUND

In your dream you are walking along a country path near the edge of a forest, the late afternoon sun warming one side of your face. All is quiet; no cars, no planes, no farm machinery in the distant fields. Just the unpaved path, the creak of trees, the stirring of grass, the low buzzing of insects.

Then something else reaches your ear, faint, just around a bend where the path turns behind a hillock. A muttering, then a strangled gurgling, retching sound, like an incompetent hangman’s handiwork in full swing. It sounds like need and almost involuntarily you break into a run.

What first strikes your senses are the clothes of the three men standing huddled under a dead tree by the side of the way. They are clearly not of your day, not even of your century. Lacking the familiar reference points that speed recognition, all you can take in at first is a jumbled mix of pointed beards, waxed moustaches, felt boots and gauntlets, elaborate embroidered capes, feathered hats, ribbons, and pantaloons.

As the details resolve into the figures of three stern men, you realize that there is also a fourth, the source of the pained gurgles, lying at their feet, hands raised in what might be abject surrender or feeble efforts to ward off their attack. It seems that a fellow traveler has been waylaid, pinned to the ground. You call out in protest. One of the men standing looks over his shoulder and notes your presence, but the three show little intention of desisting.

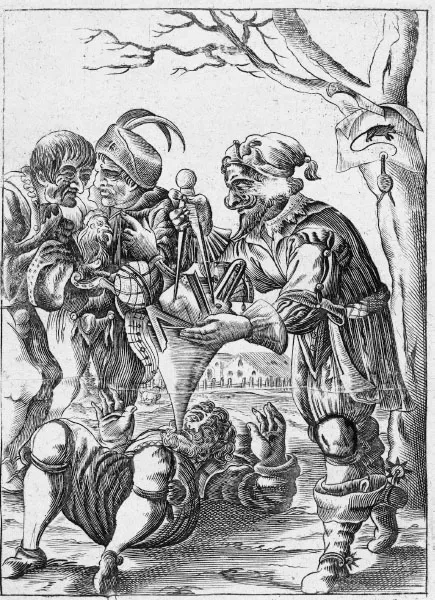

Caught between the impulse to defend the victim and your awareness of being outnumbered, you take a hesitant step closer. It is only now that you realize that although they look sharp and dangerous, the objects being used to pin the unfortunate to the ground are not weapons. At the center of the huddle is a large funnel, its narrow end inserted into the throat of the recumbent wretch. It is this that causes his helpless immobility and his inarticulate noises. Aside from this funnel, no hand is being laid on him. The three standing over him are instead engaged in a comically laborious attempt to stuff a large tangle of awkwardly shaped objects down the broad end of the funnel and into his digestive system. You catch sight of the various paraphernalia of the learned: musical scores, calipers and rulers and other tools of geometry, a globe and some related astronomical artifacts, books of grammar rules, philosophical tomes. Items crush against one another and catch on the edges. Apparently, these are teachers.

The Nuremberg Funnel, engraving by David Mannasser, ca. 1650

Most of these objects could not possibly fit through the narrow aperture at the bottom. The attempt to stuff them in seems hopeless. But the trio continue undeterred, exerting a steady downward pressure, ignoring the feeble cries from below. As they labor on, their student is motionless, going nowhere. His assigned role is to lie still and be filled up with things, not to venture forth for a destination beyond his teachers’ designs.

Filled with pity, you reach to help, to say something, but you can’t find the words. You find yourself frozen with the familiar immobility of the moments before waking. Soon you are back in the present, back in the more familiar world where you and your students engage in education together. What thoughts do you carry with you?

IS THERE A DESTINATION?

The unsettling vision of teachers stuffing things into the head of the helpless learner haunted the European imagination for a long enough period to be given a name: the Nuremberg Funnel. Teaching here means forcing a mass of dense material through a narrow tube, all the while making sure that your students stay submissive and don’t cause trouble. The student becomes a passive sufferer, an inanimate object at the teacher’s feet, contributing nothing to the process, not even chewing and swallowing, yet expected to trust that the strangulation of his voice and subjugation of his body will be for his benefit someday. This student has been made into a receptacle, not a pilgrim.

The picture is, of course, satirical. Like all memorable satire it both offers a grotesque caricature of reality (but that’s not how we teach!) and cuts close enough to give us pause (could that be how we teach?). Both the teachers and the learner are immobile; it is only the knowledge that travels from one place to another. The student has been interrupted on his journey through life, as if by a group of roadside bandits. Pinned to the ground beside the path, he is required to stop moving so that the funnel can be inserted accurately. The comically abject posture provokes imagination of other possibilities. What if the learner were standing too? Where was he going before he was knocked to the ground? What if he were walking down the path alongside his teachers, deep in conversation?

Education is traditionally associated with sitting still; an early modern satirist of education noted that one would not get far in school without “buttocks of lead”. Yet we also have a long history of talking about learning in terms of journeys. Students follow a “curriculum,” a Latin word that literally refers to the act of running or to a race track. More colloquially, we refer to a “course” of study, to “covering a lot of ground,” and to learners “falling behind,” “staying on track,” or “making good headway.” We might get “stuck in a rut,” fail to “get to” some particular piece of knowledge by the end of class, or we may “not get very far” with mastering a new skill. We “go into” some things in more detail, explaining them “step by step,” while we quickly “run through” (or even “skip past”) other things. We may “go back” to something that we need to “revisit” or add some illustrations “along the way,” and this might help us “get closer” to understanding or “reach a conclusion.” We think that education can provide a “head start” in life, perhaps enabling some students to “go far”; some learners might even be on the “fast track.” In a great deal of our talk as we teach and learn, it is apparent that we are thinking about the changes that happen during education as a form of journeying.

The journey metaphor offers us a different picture of the learner than the passive receptacle. And yet it still leaves the nature and purpose of the journey open for debate. As educational history has walked hand in hand with cultural history, imagery associated with educational journeys has shifted from travel on foot to riding in a coach and then to driving along a highway. In older Christian appropriations of the image, the path was given by God and led (at a more deliberate and deliberative pace) towards God as its destination. In the Enlightenment, the sense of destination remained, but the goal was reframed in terms of movement towards the virtuous life of the useful citizen. As travel became more widely available, the idea of education opening up new horizons took hold. The image of the 19th century explorer offered a version of travel as deliberately leaving the well-trodden path and collecting new experiences in exotic, uncharted territories. Later still, the rise of mass tourism tilted the image of travel towards comfort, efficiency, and consumption, evoking anxieties concerning educational tourists whose shallow gaze skims the main sights but does not linger for long enough to be changed. The educational path is now giving way to talk of an educational superhighway with a powerful emphasis on speed of information. Alongside these shifts came a gradual yet momentous reversal in which the experience of journeying itself overtook the pursuit of a hallowed destination as the central emphasis; simply being in motion at increasing speed and with increasing range became an end in itself. Eventually, with the fading of a shared destination, any self-chosen destination became equally valid.

The role of the teacher in all of this journeying also remains open to interpretation. Is the teacher a guide, walking the road with the students, or a signpost standing authoritatively at the crossroads, or the proprietor of a roadside strip mall hawking wares? Is the teacher to set or point towards the destination, or is the teacher’s role simply to keep students in motion, to ease their journey, and perhaps provide guard rails to keep them from straying too far from the road? Is the teacher providing students with a route — a set of steps to be followed that will successfully lead to a destination — or a map — a bigger picture of a connected whole across which various journeys can be creatively plotted? How would a pilgrim answer these questions?

THE FIRST STEP

It was quite a few years ago, while reading aloud from a Bible story book written for young children that Abram’s departure from Ur of the Chaldees suddenly became more human for me. I had grown used to thinking of Abram, the “father of all who believe,” as a model of faith, a figure challenging us to step out and follow God wherever he leads us. The biblical account is sparse — God told Abram to “Go from your country, your people and your father’s household to the land I will show you,” and in response “Abram went, as the Lord had told him; and Lot went with him” (Genesis 12:1-4). There is more than enough space around this terse summary to launch heroic tales of the man of faith sallying boldly forth and providing a glowing model of courage to the rest of us who sit mired in our comfortable apathy. I have heard that sermon more than once. And there is something to those tales. God’s plans for the world are at stake and when called away from his homeland, Abram indeed “obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going” (Hebrews 11:8).

But as I sat one evening reading the story of “Abraham’s Big Family” from a small picture book to my small son, I was moved by a simple picture of a very worried-looking Abram sitting up in bed in the middle of the night, worry lines creasing his features, his knees hugged tensely to his chest, his wife asleep beside him. The picture brought his world-changing departure down to size. The text read:

Abram trusted in God.

But he was puzzled and afraid.

He lay awake all night,

worrying,

asking himself

all sorts of questions

— which way shall I go?

— what sort of place will it be?

— will I have a nice house?

At the time I was preparing for a precarious move to another country with my family, following our conviction that God was leading us to graduate study there. Learning commonly involves leaving home to some degree, and sometimes literally and radically. It felt like a risky journey to undertake, full of unknowns, and full of very concrete, anxious, human questions that stuck to me more closely than any incipient sense of heroics. How should we travel? When can we get the best deal on flights? What sort of place will it be? Will the visa come in time? Will the studying go well? Will I be good at this? Will I have a nice house? While the children’s book account employed some poetic license, its description of Abram’s sleepless night rang true.

Abram is not alone; the Bible is filled with accounts of fraught departures and fateful travels. Adam and Eve are sent east of Eden. Abraham continues his journeys, as do his descendants. Joseph travels to Egypt, eventually followed by his family. The people of Israel are led out of Egypt and journey to Canaan, and later into distant exile, and then back again. The people of Israel journey as pilgrims, year after year, to the Jerusalem temple for the major festivals. Elijah is one of many wandering prophets. Mary and Joseph journey to Bethlehem, as do magi from a distant country. Jesus and his disciples undertake three years of itinerancy, and ultimately Jesus sets his face toward Jerusalem. Encountering the risen Christ, the disciples are told that they will be witnesses to the ends of the earth; soon after, they are scattered far and wide. Paul, among others, embarks on great missionary journeys. To read Scripture is to encounter on a regular basis people leaving the security of home and setting out into the unknown.

Sometimes the journeys begin in hope, sometimes in shame, and sometimes amid suffering. There is always a first step to be dared. The travelers are opened up to the risks of the road — but also to the faithfulness of God. The learning that takes place along the way varies: the sudden, blinding transformation of the Damascus road, the patient, systematic dialogue of the Emmaus road, and the hard life lessons of the Jerusalem road, where one might learn not to travel alone after being beaten and stripped by robbers. But always, there is the vulnerability of the road.

The Bible not only narrates a panoply of journeys, but also frequently speaks of journeying in such a way that it becomes a pattern for faithful life before God’s face, a life offered up to the risks of obedience. Psalms describing the journey to worship in Jerusalem have become patterns for prayer for believers who never literally travel more than a few blocks to attend church. 1 Peter 1:17-2:11 calls on Christians to live “as foreigners and exiles,” while Hebrews 11 connects this sojourner status with journey to a heavenly city. The pilgrimage to Jerusalem thus becomes an enduring image for the Christian life. For medieval Christians it was a commonplace that life was lived as a pilgrim journey through an uncertain world — we face life as homo viator, “pilgrim humanity.” John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress is nowadays perhaps the most famous and influential depiction of the Christian life as a pilgrimage, but it was far from the first. Gregory the Great, for instance, wrote in the 6th century:

To the just man, temporal comfort is like a bed at an inn to a traveler: he stops and he endeavors to retire, he rests himself bodily, but his mind is inclined elsewhere. Truly, sometimes he even desires to endure difficulties, refusing the prosperity of transitory things lest he be delayed from reaching his homeland by the pleasures of the road, and lest he fix his heart on the way of the pilgrim and come to the heavenly homeland without reward when it eventually comes into view. The just man, therefore, does not accumulate wealth in this world, for he knows himself to be a pilgrim and a guest in it.

Little wonder that Abram’s departure recurs in sermons. Throughout the history of the church, “journey” and “pilgrimage” have been recurring master metaphors for the life of faith before God’s face.

But does biblical wayfaring have anything to do with educational journeys? We have so far dipped in a general way first into education and then into biblical talk of journeying. What would happen if we let these two strands mingle a little, if we let images crafted to articulate the Christian journey through life, images of paths and pilgrimages, walk for a while alongside the way that we think about teaching and learnin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: Journeys and Pilgrimages

- Part Two: Gardens and Wilderness

- Part Three: Buildings and Walls

- An Ending, An Invitation

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Teaching and Christian Imagination by David I. Smith,Susan M. Felch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.