![]()

1

The Silent Era

The neighborhood at Western Avenue and Irving Park Road, bordered by Byron Street and Claremont Avenue, is as typical as any stretch of Chicago. A gas station on the corner of Western and Irving Park. Houses, apartment buildings, and condo blocks. It’s a quiet, residential area, with only the sounds of people and traffic in the air.

There is one oddity to the neighborhood: a building at the northeast corner of Byron and Claremont with a mysterious letter S emblazoned in concrete above the doorway of a condominium building called St. Ben’s Lofts. Imprinted in a diamond shape, that S is the only hint that this neighborhood was once a thriving hub for moviemaking.

The building is the last remnant of one of Chicago’s major silent film factories. At its peak, this lot was teeming with movie people, equipment, and a menagerie of exotic animals. The cacophony of those lions, monkeys, wolves, and actors has long been replaced by the more innocuous sound of traffic. The distinguishing S was the trademark emblem of the Selig Polyscope Company, where “Colonel” William Selig presided over his personal moviemaking workshop.

Though now condos, the former Selig Polyscope Co. building at Claremont and Byron still bears the trademark S. (Photo by Kate Corcoran)

A few miles north and east of Colonel Selig’s former film studio is St. Augustine College, a bilingual facility for Chicago’s Hispanic community. Located at 1333–1345 W. Argyle Street, St. Augustine is another link to Chicago’s great silent movie past. The entrance at 1345 W. Argyle features an Indian-head logo set in colored terra cotta. This doorway marks the former entrance to the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, Chicago’s most important silent film studio. Today, students walk through the same buildings once used by Charlie Chaplin, Gloria Swanson, Wallace Beery, Ben Turpin, and Essanay’s leading heartthrob, Francis X. Bushman. One of popular cinema’s first matinee idols, Bushman spent his off-hours tooling around Chicago in a lavender sedan. Fans were known to follow him in packs whenever he went shopping in the Loop. Eventually one store’s proprietors were forced to ask Bushman to no longer frequent their place of business—they couldn’t keep up with the herd that always followed the handsome actor!

In the first two decades of the 20th century, the impact of motion pictures was felt at every level of society. “The time is not far in the distant future when the moving picture apparatus will be in the equipment of every schoolhouse,” wrote one Chicago Daily News columnist in 1911. “The attempt to teach without it will be absurd.” Replace the words “moving picture apparatus” with “computer technology” and you have a better understanding of how revolutionary motion pictures were to everyday culture. In a much-criticized move, social reformer Jane Addams exhibited films at her Hull-House location at 800 S. Halsted Street. Charging five cents admission, the same as local theaters, Addams’s in-house motion picture venue became a neighborhood staple. An audience was an audience in Addams’s mind. She realized the power of motion pictures as an important tool for both entertainment and enlightenment.

Today, Chicago is a well-known world-class center for film production; major Hollywood productions like The Dark Knight (2008) showcase the city in ways the men behind Selig and Essanay studios could only dream of. Yet while the technologies have undergone radical change, the basic techniques of telling a story on-screen remain virtually unchanged. Another factor is unequivocal: Chicagoans have a creative spirit coupled with a dynamic city that puts a unique stamp on moviemaking. We have been an important factor in the film world, from the dawn of cinema and its rudimentary technology to today’s computer-enhanced blockbusters.

The Movies Come to Chicago

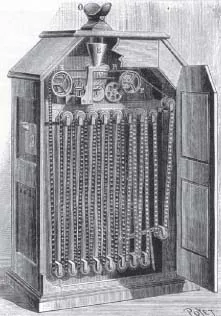

Chicagoans were first introduced to moving pictures at the Columbian Exposition of 1893 with a special pavilion devoted to Kinetoscopes, a viewing machine created by Thomas Edison’s labs in West Orange, New Jersey. Developed under Edison’s supervision by Edison assistant William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, the Kinetoscope was the forerunner to the modern motion picture. Basically, the Kinetoscope was a large box that contained several spools and a 50-foot loop of exposed moving picture film. By looking into the eyepiece at the top, viewers could watch such entertainments as Edison worker Fred Ott sneezing, dancers performing, and other simple motion attractions.

However, due to production delays, the Kinetoscopes never arrived in time, and the fair closed before the machines could be installed. Though many Chicagoans claim to have viewed Kinetoscope films at the Columbian Exposition, these early moving picture devices would have to wait a bit longer before arriving in Chicago.

Despite this inauspicious beginning, the movies eventually took their hold on Chicago in a big way. By the first decade of the new century, Chicago was a thriving center for moving picture production, while nickelodeon theaters opened throughout the city. As advancing technology brought moving pictures out of the Kinetoscope and projected them onto screens, nickelodeons became the new standard for film exhibitors. Charging five cents for admission (hence the name “nickelodeon”), these theaters operated out of storefronts and other handy locations. Musical accompaniment was usually provided by a piano player improvising popular tunes to fit the on-screen action.

With the proliferation of movies and exhibition spaces came the need for many moving picture-related jobs. Chicagoans eager to get in on the many aspects of the film industry began advertising in the Chicago Daily News, Chicago Tribune, and other newspapers, offering a wide variety of film-related services. “Moving picture music especially arranged is taught by Chas. Quinn, 59 E. Van Buren, Room 206” and “Experienced lady pianist desires position in first class picture theater. Drexel 6051” were typical classified ads, focusing on the unique musical needs of nickelodeons.

Schematic drawing of W. K. L. Dickson’s Kinetoscope, mid-1890s. (Wikimedia Commons)

Other advertisements attracted would-be movie stars with such enticing copy as “Motion picture instruction. Gilbert Shorter has new department under direction of competent director who has been connected with several feature productions. Exceptional opportunity for competent students. Day and evening classes. 50 Auditorium Building.” Another ad read, “The College Film Company, Peoples Gas building, Suite 928. Lessons: will teach limited number of students and place them in big feature films which will be exhibited all over the world. Visitors welcome. Classes for children. Terms reasonable.” A classified for screenwriters read, “Write moving picture plays. $25 weekly, sparetime: literary ability unnecessary. Free particulars. Atlas Publication Company, Cincinnati, Ohio.”

While fans flocked to the nickelodeons, studios and entrepreneurs worked throughout the city to provide moving picture entertainments. The movies became an important aspect of Chicago’s artistic and business world. At their height in the late 1910s, one out of every five movies in the world was produced in Chicago.

Selig Polyscope Company (1896–1919)

43 Peck Court (now E. 8th Street)

3945 N. Western Avenue (southeast corner of Western Avenue and Irving Park Road)

45 E. Randolph Street

William Nicholas Selig, a product of the Chicago streets, brought a good sense for show business, along with his personal style of savvy and bluster, to the fledgling movie industry. Selig was born in Chicago on March 14, 1864. As a young man ill health forced him to relocate to a more hospitable climate. He first moved to Colorado and then to California, where his well-being improved. Selig became manager of a West Coast health spa ironically named “Chicago Park.”

Eventually Selig found his calling in the world of vaudeville and sideshows. He took up magic and achieved some success as a parlor performer. Eager to expand in the world of show business, Selig adopted the sobriquet “Colonel” and put together a traveling minstrel show. One member of the troupe was a young performer named Bert Williams, who would later achieve great success as a comedian in the Ziegfeld Follies.

While traveling through Texas in 1895, Selig saw his first Kinetoscope parlor. With his show business sensibilities, the Colonel perceived the enormous financial potential of further developing moving picture technology. Selig returned to his hometown and rented office space at 43 Peck Court (now E. 8th Street), in the heart of what was then Chicago’s brothel-filled “Levee” district. Selig had no interest in opening his own string of Kinetoscope parlors. Understanding that the real money was to be in filling theaters, Selig turned his attention to developing technology that would project filmstrips onto a wall or screen.

To keep his cash flow going, Selig operated a photography studio out of his Peck Court office. His major source of income was providing carbon prints for Chicago portrait studios and working on landscape photography for the railway industry. Simultaneously, Selig looked at attempts of other early film projection pioneers. He was particularly interested in the efforts of Major Woodville Latham, a retired Confederate soldier, and Louis Lumière of France. In 1895, after seeing an exhibit of Latham and Lumière’s machines at Chicago’s Schiller Theater at 103 E. Randolph Street, Selig knew what he was up against.

Major Latham had developed a successful motion picture projection system while working on expanding the Edison Kinetoscope. Latham’s so-called “Latham Loop,” a basic setup for threading motion picture film through a projector, has essentially remained the same since its invention in 1895. Lumière, who had seen an exhibition of the Kinetoscope in Paris, coupled moving picture technology with his own ideas. His invention, dubbed the “Cinématographe,” was capable of both recording movement on film and projecting the exposed film onto a screen.

Through his talent as a conniver, Selig got his hands on Latham’s and Lumière’s devices and began experimenting with projection machines in his Peck Court office. His trial runs were successful ventures. Often Selig’s offices would be teeming with friends interested in seeing the Colonel’s moving picture exhibitions. Yet Selig still was frustrated by his inability to create his own technology.

In desperation, he turned to the Union Model Works, a local Chicago machine shop located at 193 N. Clark Street. Hoping to find a mechanic that could help develop his ideas, Selig met Andrew Schustek, the leading machinist and model-maker for the shop.

Serendipity ensued.

It seemed that Schustek had been deeply involved in creating machine parts for a mysterious foreign-born customer. This gentleman had been coming to the shop week by week, asking Schustek to reproduce specific items for some sort of mechanical device. Though the enigmatic stranger never revealed what he was developing, Schustek had taken an interest in the project and carefully sketched out plans for each piece.

Finally, Schustek learned his customer was French and had been involved with the Lumière demonstration at the Schiller Theater. Essentially, the tight-lipped client was having Schustek reproduce a Lumière Cinématographe piece by piece. Who this customer was and why he had Schustek create the device is a great unknown. The Frenchman paid Schustek $210 cash for his work (350 hours of labor at the sum of 60 cents an hour) and never left a name. What he did leave was a perfect set of plans, created by Schustek, for building a motion picture recording and projection machine.

When Selig met Schustek to explain his own interest in motion pictures, the Colonel looked on Schustek’s workspace and was surprised to see a blueprint for the Lumière Cinématographe. The two men quickly hatched a deal. Schustek left Union Model Works for employment with Selig.

Needing a larger workspace, Selig opened a second office at 3945 N. Western Avenue, located in the far reaches of Chicago. Settling into the southeast corner of the intersection of Western Avenue and Irving Park Road, Selig and Schustek devised a plan to recreate the Lumière Cinématographe, make slight changes, and give the contraption a new name to avoid any claims of patent infringement. Essentially, they created a front by which Schustek would build cameras and projectors for a sole customer—who was of course Selig. The Lumière Cinématographe, as reproduced by the two men, became the Selig Standard Camera for recording film and the Selig Polyscope, which was the projection system.

Christening his business Mutoscope & Film Company, then W. N. Selig Company, and finally the Selig Polyscope Company, Selig opened up one of the world’s first film studios at his Western and Irving Park office. Using this North Side setting as a headquarters, Selig made his first narrative, The Tramp and the Dog, in 1896. Shot in a wooded area in what is today the Rogers Park neighborhood, this simple film involves a hobo going door to door, looking for a meal. At one house he is met by an ill-tempered bulldog that chases him over a fence. Since such movie conventions as stuntmen and trained animals were years away, Selig’s comedy took an unexpected turn when the dog sank his teeth into the actor’s pants while the camera continued rolling. It was said that the look on the hobo’s face was genuine fear—here was the original method actor. Audiences, slowly warming up to this new medium, enjoyed The Tramp and the Dog as filler in between acts at Chicago vaudeville houses.

Selig Polyscope projector and logo, from the collection of Michael and Kate Corcoran. (Photo by Kate Corcoran)

Selig’s ventures into the fledgling film industry continued with smaller (and safer) productions, essentially 50-foot reels documenting the city on film. Selig Polyscope produced such turn-of-the-century titles as Chicago Police Parade, Gans-McGovern Fight, Chicago Fire Run, View of State Street, and Chicago Fireboats on Parade. Realizing that audiences wanted to see other locales besides their own neighborhoods, Selig sent camera crews out t...