What makes us laugh and why? Is comedy transformative, reparative, or rather restorative? What kinds of mechanisms are at play when it comes to comedy? And what is at stake in comic performances? This book aims at investigating the object of comedy—its core and invariances—as well as its objectives—that is, its goals, targets, and (side) effects.

It seems evident, almost too evident, to claim that comedy objectifies; that is to say, that it produces objects. When we consider an individual or group as being the butt of a joke, we are thinking about them as objects, reduced to a single trait that is associated with them. Accordingly, “the object of comedy” is understood as the target against which the complicity between the joke teller and the joke listener, or the cast and the audience of a play, is oriented. The tendency to objectify, in this specific sense, is a tendency which comedy shares with humor in general and which we could call, by way of a synecdoche, the tool of the caricature. When such a device is used by the dominant party against an underdog, for instance against sexual or ethnic minorities, we see it as foul play, no different from bullying. When the weapon of humor is used by the oppressed against their oppressor, instead, it is perceived as a legitimate means in the political arena.

In his Epistle to Augustus, the satirical poet Alexander Pope wrote that satire “heals with morals what it hurts with wit.” Like classical satire—from Horatius to Swift and from Juvenal to Voltaire—comedy may operate as a moral whip—castigat ridendo mores—aiming at criticizing both human vices and social injustices. In such cases, comedy employs humor as an ideological instrument to guide us morally to the path of the righteous.

Yet, comicality cannot be easily reduced to humor or to satire. In the classical Freudian interpretation, humor is understood as a subversive psychic device: as Freud argues, “humor is not resigned; it is rebellious” (Freud 2001, 163). Regarded as a social practice, comedy, on the contrary, reveals a much deeper ambivalence. Umberto Eco points out that, at first sight, comedy seems to be intrinsically liberating, since it allows us to break rules (Eco 1998). Indeed, comedy allows the uncanny to appear while allowing us to speak about the unspeakable, to laugh at misfortune, to turn reality upside-down. This is why, to a certain extent, in Eco’s account comedy may be considered as exerting a transformative function on the existing reality. But precisely insofar as it only involves a temporary transgression, the comical relies on and strongly reaffirms the same rules it is supposed to break. In this respect, instead of representing a way of rebelling against norms and subverting the social order, comedy may operate as a normative tool that can be used to impose codified roles and social behaviors, discriminate, dominate, and eventually oppress.

Comedy, in fact, can be extremely conciliatory, and laughter—as Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer remark—can be extremely “wrong” when it becomes a sign of surrender to the coercion of the status quo (Adorno and Horkheimer 2002). What the carnivalesque theory of comedy—historically perhaps most vocally argued for by Mikhail Bakhtin (Rabelais and His World 1984), and more recently to some extent by Simon Critchley (On Humor 2002)—does not take into account is the fact that laughter is not in itself opposed to the dominant discourse. Quite to the contrary, laughter and comedy can just as well serve as ideological weapons for reinforcing the existing order of things.

This book, however, does not concern itself with the question of the legitimacy of comedy as a political, ideological, or moral device, nor does it ask to what extent humor can be acceptable or improper. It rather addresses the question of what exactly it is in the nature of comedy that makes it appropriate for ideology in the first place. The book primarily engages with the very structure of comedy, the structure that, entre autres, allows it to be recognized by politics as a formidable instrument for exercising power. What is it that makes comedy so useful and powerful on the ideological battlefield? What does comedy have in common with power?

One could argue that comedy is power, and that the power of comedy lies precisely in its ability to produce objects, in its ability to subsume the multitude of the particular details and to round it up in a single marker, to produce the totality with one single stroke. This may be the reason why Hegel revered comedy and even considered it, as the only philosopher in the entire European tradition, as above tragedy and as a quintessentially dialectic form.

In her seminal book The Odd One In, Alenka Zupančič proposes the formula that comedy “puts the universal at work” and thus consists in the becoming concrete of the universal, or in the concrete work of the universal (Zupančič 2008, 11–22). Placing the understanding and analysis of comedy back on the agenda for contemporary critical theory, Zupančič separates what she calls “conservative comedy” from “subversive comedy.” While the predominant discussion about comedy praises its capacity to “heal”—that is, its power of delivering us from everyday routines and from the seriousness of real concerns and real obstacles—Zupančič argues for a comedy that does not offer merely comic relief from the tragedy of the real world, but rather presents us with a demand for our (more) active role in it. What she calls conservative comedy is the type of comedy that defines itself in binary opposition with the seriousness of official language and habits. Historical examples for this kind of comedy abound in the culture of carnivals, where the official rules are suspended within a clearly defined temporal and spatial framework.

Developing Hegel’s concept of comedy, a proper comic procedure, argues Zupančič, aims at grasping the symbolic, universal function itself as something concrete; and, we might add, as a kind of object. Jacques Lacan famously stated that “a madman who believes he is a king is no madder than a king that believes he is a king.” Paraphrasing Lacan, Zupančič claims that what is truly comical is not a madman who believes he is a king—which is the formula of conservative comedy—but precisely the king that believes he is a king. Her point is that real comedy does not merely result from the difference between the symbolic function of the king (or the judge, the bishop, etc.) and the flawed human being carrying out that function. In other words, comedy does not inhabit the gap between a pure ideal and its necessarily failed realization, but rather the gap or the failure within the pure ideal itself. If comedy relies on incongruity, such a discrepancy does not originate when the ideal encounters reality; it is rather an intrinsic character of the ideal itself.

Another of Zupančič’s striking examples is the baron who keeps falling in the mud: what is truly comic in this routine is not the baron’s all-too-human failure at performing the dignified symbolic function, but rather his rising up again and again, his indestructible belief that he truly is the baron. “This ‘baronness’ is the real comic object, produced by comedy as the quintessence of the universal itself,” she writes (Zupančič 2008, 32). Zupančič also draws on the concept of the object small a from Lacanian psychoanalysis, where the term designates a certain surplus involved in the pursuit of a subject’s goal: the immediate object of the pursuit—a lover, for instance—is to be strictly separated from the object that emerges in the detours of the pursuit and concerns the enjoyment brought about by the ritual of seduction itself. In fact, what Lacan calls the “object” is an inadvertent by-product of the subject’s purposeful pursuit of his or her goal. Object small a clearly has a characteristic germane to comedy. This allows Zupančič to locate the object of comedy not outside of the subject, but also not exactly within the subject itself. In a dense formula, she declares that the comic object is “a surplus of a given subject or situation which is the very embodiment of its fundamental antagonism” (Zupančič 2008, 101). We can unpack this phrase by recalling Zupančič’s own example of the baron who keeps falling in the mud: the comic object as the surplus of the subject—the indestructible “baronness” of the baron—is the embodiment of the subject’s fundamental antagonism—of the baron’s inextinguishable belief that he is the baron. In Zupančič’s account, by placing the object of comedy in the excess of subjectivity, as the by-product of the subject’s own activity, the pleasure of comedy is not explained as a pleasure that arises at the expense of an external target; paradoxically, comedy reveals that a certain kind of pleasure is to be gained at the subject’s own expense.

Through its excesses and lacks, comedy once again brings us back to Hegel. In Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel takes on the task of explaining the historical necessity of the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror, and writes:

The sole work and deed of universal freedom is therefore death, a death too which has no inner significance or filling, for what is negated is the empty point of the absolutely free self. It is thus the coldest and meanest of all deaths, with no more significance than cutting off a head of cabbage or swallowing a mouthful of water. (Hegel 1977, 360)

Even though he is evoking cabbage heads, Hegel is clearly discussing the guillotine and its terrifying efficiency in delivering instantaneous death. Hegel seems to understands this terrible device as a metaphor for, or, better, as the very image that encapsulates, the French Revolution as such. The guillotine and what it immediately stands for—the abrupt death and the absolute terror—is not understood as a necessary evil that accompanied the historical project of emancipation, as a kind of an unfortunate side effect of bringing about the idea of universal freedom, but precisely as its “sole work and deed.” In a short formula, we could say that the guillotine is the concrete work of the idea of universal freedom. If the image of monarchy is the image of Louis XIV in his majestic pose, identifying his own body with the body politic of the monarchy, then the image of universal freedom is the image of the guillotine, negating “the empty point of the absolutely free self.” What seems to be so interesting about the image of the guillotine is that it strikes us with an almost palpable sense that something is missing, that something essential is absent from the picture—something like the head. In fact, the guillotine is nothing but this absence of the head made palpable, this void made visible. And it is precisely the idea of the embodiment of the absence (of the head) that allows us to apprehend this image—as strange as it may appear at first glance—as structurally equivalent to the idea of the comic object as discussed above. It is not the head (of the king) itself that is the proper comic object, but rather the palpable absence of the head—the absence, the void, the nothingness that has itself become a thing. In his brilliant new study Liquidation World, Alexi Kukuljevic formulates this peculiar comic procedure from the perspective of the comic subject: “To make comedy requires standing in the place of one’s own absence” (2017, 6). To come back to the powerful image that Hegel gives us with his understanding of the French Revolution: is the guillotine not precisely the king himself, standing in the place of his own absence?

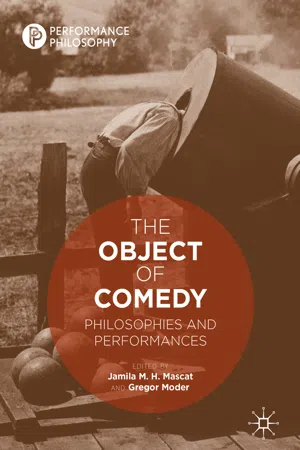

A publicity shot that was circulated to promote Buster Keaton’s silent film The General (1926) shows Keaton sticking his head into the mouth of a cannon (take a look at the cover of this book). In the large armed conflicts of the early stages of modernized warfare—The General takes place during the American Civil War—regular conscripts were often reduced to “cannon fodder.” There is nothing heroic about the lot of a conscript: he marches onto the battlefield; he dies; the end. Keaton’s publicity shot seems to take the idea of cannon fodder quite literally: Why even bother with marching to the battlefield, when you can just directly feed the cannon?

The current of comedy in this visual gag runs deeper, though. There is something strange about this publicity shot, showing us Keaton minus the head, given that the face is an actor’s most recognizable feature and his or her single most essential instrument, the very mask they...