Which understanding of our postcolonial patrimony is calling us to action now?

At first glance, there appears to be an endless number of possible answers to this momentous question, not least because it presupposes a globally dispersed, heterogeneous “we” in solidarity. A straightforward reply is also confounded because of the polarizing dispute that has arisen in the field between Marxist “revolutionary” thinkers and poststructuralist “revisionary” theorists (Huggan 2013). For these reasons alone, singling out one received legacy on which our rich body of scholarships and their responses to the world might converge seems impossible. And yet, a certain horizon of expectations and aspirations may be discernible after all, one that distinguishes a critical renewal of tradition from a mere contestation of the old on some untrodden territory. Reframing Postcolonial Studies has originated in a collective action to examine this prospect, as we bear the weight of our intellectual inheritance at the onset of another pivotal decade for the future of common humanity.

Except for anthropological investigations and multidirectional intersections between Holocaust memory and decolonization, the matter of patrimony has figured only peripherally in postcolonial studies. However, the time is now to concentrate on this topic because it runs through the latest major rearrangements of the field. Several developments account for this sea change. With the natural progression of time, there is an allegedly self-evident reason in various parts of the world for bringing the process of postcolonial detachment to an end once and for all. With the biological succession of generations, various affective and ideological attachments to the heritage of imperialism are being broken, destabilized, or reformed not necessarily for the better. At the same time, a new generation of postcolonial artists, writers, thinkers, and activists has come of age, contesting such self-centered claims and differentiating itself from formative predecessors—the ones credited with decolonization and, thereafter, with the establishment of postcolonial studies—with a critical consciousness of inheritance and legacy. What is reframing postcolonial studies today stems from the conflict and solidarity in this acute “non-simultaneity” (Ungleichzeitigkeit), as several generations respond similarly, differently, and relationally to colonial fantasies and postcolonial resurrections (Bloch 1962, p. 104).1

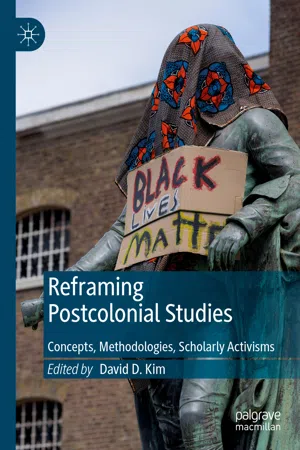

Given the international and multidisciplinary scope of the field, it is essential to understand to what extent this dynamic process mounts a response to the most pressing concerns in the world, including racism, sexism, nationalism, public health, inheritance, war, and sustainability. The main task involves challenging the times, as they are dictated by oppressive cultural, economic, political, and religious forces, and engendering alternative linkages of past, present, and future. Such transformative action is only possible when scholars, teachers, students, activists, artists, writers, and filmmakers recalibrate their vocabularies, which have been important for the field, in light of the latest postcolonial struggles. For this “concept-work” to be effective, they need to be invested in methodological innovation and open up postcolonial criticism to incisive political activism (Stoler 2016, p. 17). Without such critical and creative coordination, postcolonial inheritance would survive mostly as a self-absorbed academic discipline without much worldly impact. That is the reason why this volume seeks to close the loop by taking a fresh look at the three parts of contemporary postcolonial studies: living concepts, cross-disciplinary methodologies, and bold intersections of scholarship and activism. The following investigations examine how they have recently changed through individual and cooperative efforts to decolonize museums and public spaces marked by colonial signposts, to cultivate community organization and transversal affinity in times of political, ecological, and pandemic crises, and to redress questions of reconciliation, reparation, repatriation, or retribution in pursuit of “a truly universal humanism” (Shih 2008, p. 1361).

To be sure, the force of “reconstructive intellectual labor” has been transforming the field since the very beginning (Gilroy 1993, p. 45).2 With gripping references to Négritude intellectuals, other African, African American, Indian, Australian, Canadian, and Caribbean writers, as well as West European thinkers, the first generation of critics gave rise during the 1980s and early 1990s to postcolonial theory, which changed the academic landscape primarily in anglophone countries.3 The impetus behind a second, more global postcolonial wave a decade later was again this indefatigable sense of self-reflexivity, as more and more academics and activists, discontent with “Europe” as “the sovereign, theoretical subject of all histories,” shifted their focus from conceptual dichotomies, political impositions, and literary analyses to ambivalent translations, subversive displacements, and material reconsiderations (Chakrabarty 1992, p. 1).4 After the field had become established first in departments of English, history, and comparative literature at North American, British, Indian, and Australian universities, this subsequent wave reshuffled the field beyond its concentric constellation by applying conceptual, methodological, and historical findings to other cultural, disciplinary, linguistic, and national contexts, and by interrogating theoretical formulations with historical inquiries into different places of alterity. In addition to scrutinizing analytic terms whose “insight” was not deemed to travel “well across adjacent disciplines and scholarly fields,” scholars, students, artists, and activists worked more deliberately on non-Western, Indigenous, early modern, and minor European ways of knowing (Scott 2005, p. 389). Their collective action, enhanced by professional organizations, libraries, and other university-led initiatives, interrogated “canonical knowledge systems”—even those within the relatively young field—and fruitful results came directly from far-reaching exchanges across “disciplinary boundaries and geographical enclosures” between literary scholars, historians, and colleagues in neighboring areas of study such as anthropology, geography, sociology, art history, gender, film, translation, performance and Holocaust studies, and, more recently, international human rights, as well as environmental, digital, and urban humanities (Gandhi 1998, p. 42; Prakash 1995, p. 12).5

Roughly four decades in the making, then, the vibrant character and diversity of postcolonial studies have been energized by a tireless spirit of “reenactment” (Prakash 1995, p. 11). This reconstructive dynamism has been instrumental in posing a strong opposition to skeptics who believe that to live well in postmodernity is to bid farewell to postcolonial remains.6 With incisive investigations of archival conventions, governmental records, photographs, paintings, films, maps, performances, memoires, travelogues, letters, oral traditions, digital databases, and literary narratives, postcolonial critics have kept their original spirit alive by revealing “interrelated histories of violence, domination, inequality, and injustice,” as well as “the hidden rhizomes of colonialism’s historical reach” beyond the transitional period of independence, especially in the lives of women and children, victims of war, racialized ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, and working-class families (Young 2012, p. 20). Alarmed by “the duress” with which imperial formations continue to accrue in postmodernity, they reaffirm arguably the most foundational lesson in postcolonial studies that the post in postcolonial is irreducible to a temporal marker (Stoler 2016, p. 7).7 Having identified earlier blind spots in anglocentric literary and historical approaches to colonialism, contemporary postcolonial projects illuminate how heterogeneous and interconnected illiberal democracies are at an international scale, and why these unequal societal structures are built upon the ruins of past imperial regimes.8

More recently, this work has engaged a new generation of critics, artists, and activists who draw upon the trailblazing oeuvres of anticolonialism, the political imaginaries of the Bandung period, and later postcolonial criticisms to reshape the world in tune with their own anxiety, courage, hope, curiosity, enthusiasm, and grievance. They are exemplifying what Hannah Arendt calls “action.” She argues that this capacity, which comes with the status of being “newcomers and beginners,” is inherent to each generation and connotes both the right and the ability “to take an initiative, to begin (as the Greek word archein, ‘to begin,’ ‘to lead,’ and eventually ‘to rule,’ indicates), to set something into motion (which is the original meaning of the Latin agere)” (Arendt 1958, p. 177).9 Although Arendt falls short of specifying how this beginning owes itself to what precedes it, it is useful here for conceptualizing how the lessons of past colonial, decolonial, and postcolonial activities are being reframed in currently transformative debates and community-based organizations. A combination of old and new action works up and down generational lines to revitalize resilient, forward-looking initiatives in reparative justice.

Reframing Postcolonial Studies consists of carefully selected case studies that shed light on this action. Written by scholars of dif...