On August 24, 2009, on our second day of participant observation at a shelter for migrants in southern Mexico, the administrator told us in a hushed tone that he would be seeking psychological counseling for a new arrival to the shelter, a young woman from El Salvador who had been kidnapped and raped by one of her captors. From the office area where we spoke, he discreetly pointed out a tall, attractive woman in her twenties with a long dark ponytail. She stood outside in the shelter’s central patio, behind a fortyish woman who sat on a folding chair, drying her freshly washed hair in the sun. The administrator explained that the older woman was an elementary school teacher from Honduras, and that the two women had been kidnapped and held hostage together, along with the teacher’s nine-year-old son, a little boy who crouched down on the concrete to play with a toy car while keeping one eye on his mother. In what seemed like a touching display of Central American and intergenerational solidarity, the younger woman gently wielded a plastic comb to detangle the hair of the older woman. On the surface, this was yet another account of the Central American migrant victimization in Mexico that was already being widely documented by journalists, scholars, and human rights advocates. For instance, in 2009, a Mexican National Commission of Human Rights report concluded that more than 10,000 migrants had been kidnapped in a six-month period. Yet as we spent the day at the shelter and spoke with the two women for hours, the categories of victim and victimizer soon became less distinct.

The younger woman told us that she was fleeing violence in El Salvador and wanted to seek asylum in the United States. After her journey was interrupted by the kidnapping, she had been held prisoner for several weeks in a house in the city of Reynosa, Tamaulipas near the U.S. border, across from McAllen, Texas. When we spoke separately and privately to the older woman, however, she told us that the younger woman was an accomplice to the kidnappers, who eventually identified themselves as part of a major drug cartel. The two women had met at a shelter for migrants in the north-central state of San Luis Potosí, where the schoolteacher had stayed the night as she traveled north with her youngest son to try to join her two adult sons in Houston. The young woman lured the older woman onto a bus with the offer of a cheap smuggler, a guide to help cross the Mexico–U.S. border. Yet after a couple of heavily armed men suddenly refused to let anyone off the bus for any reason and later imprisoned the passengers together with dozens of other migrants in the house in Reynosa, it became clear to the schoolteacher that her smugglers were in fact also her kidnappers. As the days went on, it also became obvious that the young woman was given privileges that the other hostages did not receive, such as better food and more freedom of movement. She seemed to be the girlfriend of one of the kidnappers. It was only when the Mexican army suddenly descended on the house and released the migrants that the younger woman began to present herself as a victim, the schoolteacher told us. Still, she acknowledged, to win her own release, the kidnappers had told her that she would also have to visit shelters for migrants to recruit at least ten new victims. If she refused, they said, they would kill both her and her youngest son, even though her adult sons in Houston had already sent five thousand dollars in ransom for her release. She was pondering this dilemma when Mexican soldiers burst into the house and rescued the hostages.

Fearing for her life and for that of her son, the schoolteacher swore us to secrecy. She asked that we not report any of what she had said to the shelter authorities but that instead in our book we tell “the truth” about the real buenos and malos, the good guys and the bad guys. Yet the truth felt slippery. As scholars, not police investigators, we weren’t qualified to determine the degree of complicity or coercion between the kidnappers and the young Salvadoran woman. And might the schoolteacher, had she not been rescued just in time, also have been forced into recruiting new kidnapping victims, thus shifting her from the category of victim to the category of villain? Is anyone essentially a victim, villain, or hero, or do those labels just describe the roles that people play under specific circumstances? As we mulled over these questions, we found ourselves haunted by something else that the schoolteacher had said with a smile: “My story is better than a Mel Gibson movie!” By this she meant that she had experienced a violent ordeal with elements of adventure, yet like the hero of a Hollywood movie, she had survived to tell the story. Her boast also pointed to another truth that we felt more qualified to explore: Her story had a value to us as scholars of performances surrounding migrants, and potentially to others—journalists, artists, activists, humanitarian workers, and other scholars who might take an interest in her life and if not reward her materially, at least show her kindness and pay attention to her suffering. As Sidonie Smith notes in her analysis of the circulation of stories of ethnic suffering , witnesses often know that their stories have a value on a global human rights marketplace. Yet to get their stories out they must turn them over to “journalists, publishers, publicity agents, marketers, and rights activists.” Such intermediaries, including scholars, also frame stories and performances by and about migrants so as to participate in what Smith identifies as “the commodification of suffering , the reification of the universalized subject position of innocent victim, and the displacement of historical complexity by the feel-good opportunities of empathic identification.”1 In other words, when we sell stories of suffering on an international market we reinforce the notion of the innocent victim and entertain consumers of such narratives by encouraging them to identify with victim-heroes.

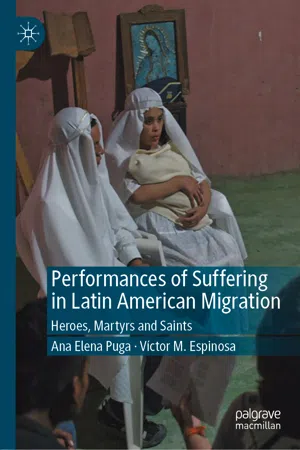

Performances of Suffering in Latin American Migration: Heroes, Martyrs and Saints is intended for scholars and activists who want to better understand how Latin American migrants to the United States grapple with a global market in performances of suffering . We argue that artists, advocates, journalists, and yes, scholars, often tend to highlight migrants’ status as victims, encouraging migrant victims to perform their suffering—not to fake it, but to express it publicly on demand—in return for respect for rights that in fact are often already theirs, at least on paper. As we detail in the chapters to follow, migrants themselves sometimes collaborate in such performances and sometimes resist, to varying degrees. We encourage scholars, activists, humanitarian workers, and other advocates for migrants to reflect on how their practices sometimes resemble those of directors of theater , in that they craft scripts, assign certain roles to certain actors, and supervise the design of mise-en-scène. What are the consequences of casting certain migrants, or helping certain migrants cast and stage themselves (often in response to others casting them as villains) as pitiful victims or triumphant heroes? Strategies that involve casting migrants in what are essentially melodramas, we argue, are often used to try to win respect for the rights of the oppressed. As Jon D. Rossini has noted, however, melodrama is a double-edged sword that runs the risk of perpetuating the stereotyped marking of victims-as-victims.2 While we stress that melodramatic castings can undermine agency, the potential to carve one’s own course through the world, we also acknowledge that performances of suffering sometimes seem like the only way to move the migrant from outsider to insider, from undeserving to deserving of rights, from criminalized “illegal alien” to celebrated model citizen.

Supporters of migrant rights might be surprised or even offended to hear us contend that they are using melodramatic strategies to represent and protest the suffering of migrants. Readers, especially readers who are not scholars of theater , readers who have seen close-up the physical and psychic pain that migrants are forced to undergo, might understandably dismiss the term “melodrama” in its everyday usage as a derogatory expression that questions the truth of migrant hardship and mocks as false exaggeration advocates’ efforts to make it legible. Nothing could be further from our intention. On the contrary, with respect and admiration for migrants and their advocates, in order to further understanding of both performance and of migrant-rights advocacy, we maintain that a scholarly term drawn from theater and film studies, melodrama, accurately describes not only the genre of much contemporary cultural production focused on migrant suffering but also the mindset with which we represent and comprehend such suffering. Melodramatic performances of migrant suffering, we argue, are especially valued and earn rewards on a global market in cultural production, which in turn reinforces how we perceive future suffering. Performances of Suffering in Latin American Migration asks readers to take a step back to reconsider how we think about migrant suffering, how we stage it, and how we circulate it.

Our study explores the following questions: What is gained and what is lost by our reliance on spectacle and melodrama in performances by and about migrants? Can the suffering of migrants serve a redemptive purpose, as much melodramatic performance would have it? Or does migrant melodrama merely construct communities of privileged sentimental audiences who indulge in fantasies of egalitarian participation with the undocumented? Does the tendency to perpetuate an economy in which suffering is exchanged for human rights then ultimately serve a conservative agenda that naturalizes migrant hardship as inevitable and unavoidable, the “price you pay” for belonging? Or are certain ways of deploying melodrama more efficacious than others in repr...