eBook - ePub

Selling Textiles in the Long Eighteenth Century

Comparative Perspectives from Western Europe

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Selling Textiles in the Long Eighteenth Century

Comparative Perspectives from Western Europe

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Textiles are a key component of the industrial and consumer revolutions, yet we lack a coherent picture of how the marketing of textiles varied across the long 18th century and between different regions. This book provides important new insights into the ways in which changes in the supply of textiles related to shifting patterns of demand.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Selling Textiles in the Long Eighteenth Century by J. Stobart, B. Blonde, J. Stobart,B. Blonde,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

An Education in Comfort: Indian Textiles and the Remaking of English Homes over the Long Eighteenth Century

Beverly Lemire

In 1696, an anonymous English merchant ‘J.F.’ produced a small volume, The Merchant’s Warehouse Laid Open: Or, the Plain Dealing Linnen-Draper. He dedicated this book to Princess Ann of Denmark.1 The encomium he offered the princess speaks to J.F.’s political proclivities; he evidently supported the insurgent Protestant Whig dynasty now on England’s throne. Perhaps he was also one of the newly rich that had profited from Whig political connections, as commerce was of high concern to the new regime. J.F. was certainly a seasoned commercial man, well versed in the international traffic in textiles, both goods produced in Europe and those transported from Asia by English fleets. The East India Company specialised in the importation of Indian textiles to Europe after 1660 and J.F. clearly responded to the local retail changes that resulted from this project.2 The volume he wrote was slim but its ambitions were large and reflect the transformational processes under way in England’s markets and English homes, as more varieties and larger quantities of cloth were purchased and employed in studied ways. The transmission of quilts and quilt culture illustrate this material innovation. Indian quilts modelled a new form of comfort, being striking visual and sensual additions that demanded new skills in textile management, such as J.F. aimed to provide. Learning to consume successfully and attending to the new material culture of the home are the focuses of this chapter.

Global trade represented new trials and new opportunities for consumers and retailers; for while many welcomed the enticing bales of Indian cottons, too little was generally known about the qualities of these commodities and no guild guaranteed value. Indeed, the East India Company struggled to enforce standards. In this chapter, I consider the challenge of educating early modern women and men about new textile goods. Ultimately, Indian cottons were widely used to refashion domestic spaces with items like quilts – the spread of product knowledge was indispensable in this transformation. Comfort became a newly achievable goal for a wider range of citizens over the long eighteenth century and the model of middle-class satisfaction so aptly reflected in Low Country culture and practice became the aim of new generations of Europeans including the English.3 How was comfort achieved? Changing architectural styles and household technologies have been studied for their effects.4 But other mechanics of creating comfort must be evaluated. New facets of cleanliness, comfort and display, with its attendant bodily satisfaction, involved an evolving textile technology system. The smell and feel of household linens became a subject of note, including the desired whiteness of what in France was termed gros linge or the ‘great linen’ that dressed beds, windows and tables.5 Consumer education and changing sensibilities combined with the development and deployment of new textile forms to coalesce around the great mission of domestic ease. As John Crowley notes: ‘Comfort, like gentility, was something to be learned and expressed.’6 This was not an exclusively English phenomenon; but this case study is framed by predominantly English examples. Similarly, cotton will be the core commodity addressed.

Instructional manuals became increasingly important in the crafting of households, used directly and indirectly by housewives and their servants, including greater numbers of cookery books and guides to household management aimed at achieving new standards of material life.7 Retailers, household mistresses and domestic servants stood at the heart of this process, sharing and exchanging information, supplying and shaping the new materials of taste and comfort. As there were more domestic textiles to be managed with each generation,8 laundry also proliferated, demanding ever-higher standards of cleanliness as emblematic of respectable family life. New elements of hygiene and domestic order evolved. Likewise, women devised new mediums of expression within this regime through the integration of washable Indian bedding into English homes, with the spreading use of quilts to warm and decorate beds. In sum, the sensory experience of domestic life took new forms and the administration became more laborious as larger quantities of textile embellished the home.

The education of buyers: achieving the technology of comfort

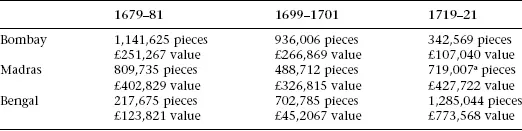

The noted historian of technology, Thomas Parke Hughes, defines the social and physical facets of technology as those that combine the force and talents of a range of occupations aimed at designing and controlling a ‘human-built world’. Hughes emphasises the creative, functional and aesthetic dimensions of technological systems, an analysis that fits well the complex trade, sale and uses of textiles in the eighteenth century: a system of textile technology that helped define domestic life and articulated contentment. Information and its dissemination are critical to a technological system such as this, enabling the modification of domestic spaces through textiles, part of the remaking of the ‘human-built world’ of eighteenth-century England.9 In this context, the scale of overseas imports represented a significant challenge. The East India Company (EIC) strived to enforce product standards, but it faced a dauntingly long supply chain, combined with negotiations in a complex cultural setting where English agents often competed for products.10 Despite the difficulties, the appetite for Indian fabrics grew among Europeans. The EIC became the largest importer of cotton textiles in Europe, and Indian cotton and silk textiles represented from 49 per cent to 60–70 per cent of EIC imports between 1664 and 1678. Over a million and a half pieces of cloth arrived in London from India in 1684 at period of peak importation and, as Table 1.1 illustrates, the demand for these goods ignited sustained market activity.11 Of necessity, consumers underwent a course of education about these commodities, one that took decades.

Jan de Vries observes that new goods must be ‘recognizable’ to be quickly and easily absorbed into existing consumption contexts.12 At first glance Indian cottons did not seem to test shoppers’ understanding – the apparent likeness of cotton to linen allowed this commodity to be eased into the European marketplace. But, despite the seeming similarity, the characteristics of Indian cottons differed from their European comparators, not least in the varieties arriving from several regions of India. Sound judgement as to quality and value could only be secured through experience, by repeated interactions. Cutting, stitching, wearing and washing would reveal the flaws, foibles and functionality of these textiles in their applied uses. Importers faced logistical challenges in bringing goods to market half-way around the world and there were also yawning gaps in this textile technology system in the diffusion of product information.13 Merchants, retailers and consumers all had to master facts about goods from India, making decisions on their best information. The role of shopkeepers in informing clients about their stock demanded at least some knowledge from the buyer – the more informed the buyer, the better the chance of a good deal.14 As Claire Walsh observes:

Certain goods required extensive knowledge that could be gained only through familiarity and actual use (and never more so than in periods without branding and standardization). … Knowledge encompassed suppliers, prices, innovations, styling, and cultural and social inflections related to that object group.15

Preparation for the retail contest was essential when faced with the deluge of fabrics at shop counters or from pedlars’ packs.16 Shopping as a ‘tactile and verbal’ event involved jousting for advantage.17 Friends, family or employers routinely shared knowledge, debating the merits of the goods they saw, felt and weighed in their hands, part of the critical sensory assessments in the selection of goods.18 But looks could deceive; as could the surface feel of a fabric, finished in such a way as to disguise imperfections embedded within the cloth. Tricks and deceits were endemic in early modern products.19 And those offering goods for sale were often prepared to mislead if it was to their advantage, ‘especially those Cloths that are bought and sold by Pedlars’.20 J.F.’s book aimed to distinguish the best from the worst of the dizzying array of fabrics available in virtually all parts of the country, to educate all social classes: ‘How to Buy all sorts of Linnen and Indian Goods: Wherein is perfect and plain Instructions, for all sorts of Persons, that they may not be deceived in any sort of Linnen they want. Useful for Linnen Drapers, and their Country Chapmen, for Semstresses, and in general for all persons whatsoever.’21 Selling textiles was a core commercial activity, a commodity essential for all, for rich, middling and humble folk. J.F. asserted that all could profit from his detailed assessments. The pitfalls were many. The sheer diversity challenged the skills of shopkeepers and housewives to judge wisely, to avoid fabric that looked ‘well to the Eye, but when it comes into Water falls into pieces’.22 This volume distilled years of experience into a few pages, being the first of its kind to publish assessments of such a range of fabrics.

Table 1.1 Imports of Indian textiles by the English East India Company

a 1722 data are used, as there are no data for 1721.

Source: Chaudhuri (1978), pp. 540–545.

I am well assured, it will prove as general an assistance and good in Worldly Affairs, as any yet written, both to Rich and Poor, by reason the Rich and Wealthy do often buy great quantities of Linnen, and so consequently, when they are deceived with bad Linnen, must be deceived of great Sums; and the Poor having but little Moneys to lay out, and that little perhaps, hath been saved out of their Families Bellies, to procure a little clean Linnen to put on their Backs, and if they are deceived of that, can by no means get more to supply themselves withal; but if they take the advice of this little Book, they will not fail of their expectation … of any sort of Linnen, or Indian Goods … [or] be deceived by the most crafty Dealer.23

Advice books, like J.F.’s, were a familiar genre by 1700 and proliferated during the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction. Selling Textiles in the Eighteenth Century: Perspectives on Consumer and Retail Change

- 1 An Education in Comfort: Indian Textiles and the Remaking of English Homes over the Long Eighteenth Century

- 2 Making the Bed in Later Stuart and Georgian England

- 3 Customers and Markets for ‘New’ Textiles in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Sweden

- 4 The International Textile Trade in the Austrian Netherlands, 1750–1791

- 5 Material Marketing: How Lyonnais Silk Manufacturers Sold Silks, 1660–1789

- 6 Rural Retailing of Textiles in Early Nineteenth-Century Sweden

- 7 New Products, New Sellers? Changes in the Dutch Textile Trades, c. 1650–1750

- 8 ‘According to the Latest and Most Elegant Fashion’: Retailing Textiles and Changes in Supply and Demand in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Antwerp

- 9 Taste and Textiles: Selling Fashion in Eighteenth-Century Provincial England

- 10 Luxury and Revolution: Selling High-Status Garments in Revolutionary France

- 11 Second-Hand Trade and Respectability: Mediating Consumer Trust in Old Textiles and Used Clothing (Low Countries, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries)

- 12 Urban Markets for Used Textiles – Examples from eighteenth-Century Central Europe

- Select Bibliography

- Index