eBook - ePub

Consumption, Informal Markets, and the Underground Economy

Hispanic Consumption in South Texas

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Consumption, Informal Markets, and the Underground Economy

Hispanic Consumption in South Texas

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Using original qualitative ethnographic field interviews and quantitative field survey results, Consumption, Informal Markets, and the Underground Economy explores the rationale for and model of 'off the books' consumption in a borderlands environment.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Consumption, Informal Markets, and the Underground Economy by M. Pisani in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economía & Política económica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EconomíaSubtopic

Política económica1

Introduction

Abstract: This chapter introduces the concepts of informal and underground consumption or “off the books” consumption within the South Texas (US) economic landscape. The literature supporting the study of “off the books” consumption is reviewed and contextualized.

Keywords: Informal Consumption, Underground Consumption, “Off the Books” Consumption, South Texas Borderlands, Consumption Risk

JEL codes: D11, D12, K42, O17

Pisani, Michael J. Consumption, Informal Markets, and the Underground Economy: Hispanic Consumption in South Texas. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. DOI: 10.1057/9781137333124.

Minerva Castillo1, a 20-year-old Latina and math tutor, believes that purchasing products outside of the normal retail environment saves money and helps others. Minerva’s most recent “off the books” or informal purchase was jewelry at a local South Texas flea market. Minerva recalled, “It is not wrong if both people [seller and buyer] have a mutual agreement. The economy is suffering, so [acquiring goods and] services ‘off the books’ is a great way to save money and help others.” Within Minerva’s brief story appears a need to save money, a weak economy, moral acceptance of alternative consumption channels, and mutual benefits accruing to buyer and seller. Minerva is a typical consumer of extralegal goods.

The informal and underground economy is a common feature in the life of South Texans.2 Nearly every resident (98.9%) of the region participates, at one time or another, as a consumer in this economy. Rich and poor, old and young, Hispanic and non-Hispanic participate. More than half of the population reports consuming the following informal goods or services: food plates (70.3%), tamales (67.0%), auto repair services (66.3%), fruits and vegetables (64.1%), ice cream and paletas or snow cones (60.5%), tire repair services (53.8%), and flowers (52.1%). Informal consumption is ubiquitous and is the subject of Chapter 3.

While not as prevalent, consumption of underground goods is widespread in South Texas particularly for those goods with little risk of penalty or imprisonment. Low risk goods such as pirated music, software, movies, cable and internet service are consumed by nearly two-thirds (64.6%) of the population. During a recent shopping trip to a local flea market or pulga, Enrique Treviño said that he “bought pirated movies . . . for $2” apiece. When asked about the legality of his purchase, Enrique bluntly stated: “Risk is not a factor when saving money is a concern.” Dina Sanchez, however, looks both ways before engaging in the public purchase of pirated goods. She noted, “I was at the flea market buying unauthorized movies and there was a raid. Good thing word gets around fast; we just walked away and pretended to see something else in another stand.” Unlike low risk underground goods, higher risk underground goods consumption is less pervasive. This follows a risk consumption pattern whereby increased consumption risk reduces the consumption rate of underground goods (the topic of Chapter 4).

This book explores the household consumption of informal and underground goods and services in South Texas on the basis of a 2010 survey of local households. This introductory chapter sets the stage for the exploration of “off the books” consumption of informal and underground goods at the household level. Applicable literature of “off the books” consumption from around the world is presented. Particular attention emphasizes recent research undertaken in developed and emerging/developing market contexts. From this wider perspective, the focus narrows to South Texas, where the unique geographical context of the South Texas borderlands is discussed. The scholarly literature for both informal and underground consumption are introduced, developed, and contextualized. A selection of brief qualitative vignettes that personalize the dimension and decisions associated with “off the books” consumption in the region enrich the narrative throughout the book. A model of consumption of these informal and underground goods is introduced in Chapter 2.

Literature review

Consumption of “off the books” informal goods and services has received scant scholarly attention, particularly in developed market contexts where informality comprises a relatively small part of overall economic activity. In developed economies, informality in the public sphere is often viewed, if recognized or understood at all, as a fringe economic oddity, mostly to be ignored. However, informality is a major public policy concern in developing contexts where often a majority of all economic activity falls within this economic sector. The South Texas economy regularly bridges both developed and developing contexts.

Informal goods and services are part of the informal (or “off the books”) economy where sellers and buyers meet. The informal economy consists of market transactions that avoid government regulation, oversight, and/or taxation, though these same transactions could have been conducted legally under the auspices of government monitoring (Portes et al., 1989). Much of the literature on informal markets focuses on the producers of informal goods rather than the consumers of such goods.

The underground economy, in contrast, involves economic activities that are not only evasive of governmental oversight, but criminal in nature (Richardson & Pisani, 2012). Because of its explicit criminality and longstanding public policy concern, the literature within this domain is much more robust.

Informality

The distinction between the informal and formal economy is primarily a twentieth-century division. As the power and enforcement capabilities of the state have increased, so too has the state’s ability to regulate commerce and dictate its legal framework. Where states and their institutions are weak, the informal economy flourishes. Where states and their institutions are strong, the formal economy dominates. Nevertheless, the informal economy exists in both strong and weak states—the size and scope of informality adapts to the local social, political, cultural, and economic environment.

The term “informal” as related to economic activities first originated with Keith Hart, an economic anthropologist with research ties to West Africa. Hart (1970, 1973) argued that economic circumstance and lack of employment alternatives pushed many in West Africa to seek available, albeit informal, income earning opportunities to survive regardless of work protections or government oversight. This lack of worker protection or government oversight was termed informal. Astutely, Hart (1973) discussed the heterogeneous nature of informality as: a continuum between formal and informal work; different for the self-employed and wage workers within the informal sector; and the legitimacy of informal work itself, otherwise potentially legal (if reported) work versus criminal activities which by definition is illegal in all respects. Hence a duality of sorts was constructed between informal and formal and between informal and criminal.

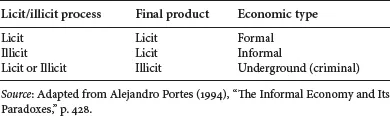

Others have expanded upon Hart’s seminal work; most notable among them is sociologist Alejandro Portes. Portes’ typology of informal and formal derives from the processes involved in the production and distribution of goods. Accordingly, informal goods are by definition goods which society has accepted as legal, yet their manufacture and/or distribution were undertaken outside of government regulation and oversight (see Table 1.1). Goods which are illegal regardless of their manufacture or distribution fall within the underground economy.

For example, Irma Mendoza from rural Hidalgo County is motivated to engage in the informal economy if “1) it is a good deal, and 2) it is at the right time and the right place.” As a local business owner, Irma buys informally “for both personal and business” reasons. Irma noted that her most recent informal purchase was a 50lb bag of onions for $10, stating “we bought them [onions] because we had run out and if we had not bought them from the man [roadside vendor], we would have to go outside of town to purchase them.” In this case, the onions are a licit good; however the transaction occurred outside of government purview (unreported income and sales). To minimize risks, Irma buys nothing “more than $10” and tries to deal with only those “we trust and know”.

TABLE 1.1 A typology of formal, informal, and underground goods

Consumption informality

The acquisition of informal goods sometimes occurs in plain sight without much interference from government authorities. In Slovakia, cigarettes and clothing are often purchased openly and informally, raising little attention from the government (Karjanen, 2011). In the United States, food purchases, particularly those found along roadsides, have a long history and tradition of informal exchange (McCrohan & Smith, n.d.). At the national level with a large extralegal sector as in Italy, economic researchers have found buyer participation in the extralegal sector may smooth the unevenness of income throughout the business cycle (Busato et al., 2008). However, the negative spillover of “off the books” consumption in Italy produces negative national wealth effects because private and underground consumption are complementary and deleterious to economic growth (Chiarini & Marzano, 2006).

Consumption informality predominately stretches income (Pisani & Sepulveda, 2012; Staudt, 1998; Williams, 2008). Within urban England, Williams (2006) and Williams and Paddock (2003) surveyed household consumers’ purchasing behavior in regard to 17 informal household services. According to Williams (2006), these alternative consumption practices and purchases comprised 2 percent (e.g., home equipment repair) and 10 percent (e.g., home improvement services) of common household services. While these ranges are relatively quite small, they are subject to income constraints—or to stretch income—and perhaps consumer choice. Williams and Windebank (2005) identify differing levels of informal consumption of household goods by income, with poor households informally consuming 78 percent of selected household purchases, 22 percent of middling income households, and less than 1 percent of affluent households, suggesting an inverse relationship between income and informal consumption. Williams (2006) also reports that cash transactions facilitate the consumption of informal goods.

In addition to cash and economic necessity, some investigators note the attitude of consumers toward extralegal purchasing may enable “off the books” consumption. In their study of the “gray-market” for smart phones in Taiwan, Liao and Hsieh (2013, p. 420) found that “consumers’ attitude toward counterfeit goods has the strongest impacts on consumers’ willingness to purchase gray-market smartphones”. That is, consumers who were predisposed toward buying extralegally with little moral inhibitions were more likely to engage in gray-market smartphone purchases. For some Taiwanese, the novelty of possessing a smartphone mattered, but not as much as the acceptance of purchasing extralegally in the consumption of gray-market smartphones.

Another enabling factor of consumption informality is trust, oftentimes attributed to embeddedness and social capital accrued through familial and friendship networks (Richardson & Pisani, 2012; Williams, 2008; Pisani & Yoskowitz, 2001, 2005). Additionally, the mutual benefits derived from the market exchange to both buyer and seller, usually enumerated by the buyer as altruism, supports an informal consumption rationale (Pisani & Sepulveda, 2012; Williams, 2008). Williams (2008) furthermore notes that in Europe that informal consumption may also be the result of obtaining faster service and a good that is no longer available in the formal marketplace. International borders may also both facilitate and deter informal consumption. In a previous study, I found that the US-Mexico border may act as a lever permitting informal consumption by utilizing uneven national regulations, bureaucratic pliancy, and enforcement differentials (Pisani, 2013).

For example, Mario Gonzalez of Mission, Texas hired undocumented labor to build his home. Mario explained, “I hire them because it is cheaper and saves a lot more when I do not have to report it.” Mario believes “he is just trying to help them [the undocumented workers] by giving them jobs so they can provide for their families. It is a win-win situation.” The sense of helping others through informal consumption as a form of altruism is a persistent theme in South Texas.

Consumption of underground goods

There is a growing academic literature on pirated (Husted, 2000), counterfeit (Eisend & Schucher-Güler, 2006; Naim, 2006), and smuggled goods (Andreas, 2013). The underground production and consumption of underground goods in North America long predates the birth of the United States and the trade in underground goods is a centuries’ long tradition which is as dynamic as the history of the United States (Andreas, 2013).

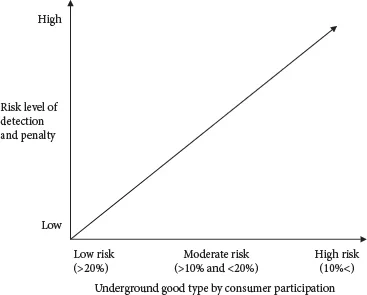

Underground goods are criminal by law and cannot be exchanged in a legal environment.3 Contemporary examples are illegal drugs (e.g., crack, heroin) and stolen goods. Underground goods make up the underground economy which has been described as “economic activities that are not only evasive of governmental oversight, but are also criminal in nature” (Richardson & Pisani, 2012, p. 20). However, not all underground goods are “made” and consumed equally. That is, some underground goods are subject to more government scrutiny and consumer acceptance than others. Hence a consumption risk platform or tradeoff exists between the type of underground good and potential penalty. This risk trade-off for pirated CDs/DVDs is supported by the work of Wang4 (2005) and also by Chiou et al. (2005) for music piracy.

FIGURE 1.1 Risk levels of detection and penalty of underground consumption

In this book, underground goods are grouped by detection and penalty risk: low, medium, and high. I have organized these groups by consumer participation rates. Low risk underground goods have consumer participation rates of over 20%, medium risk goods have consumer participation rates between 10% and 20%, and high risk goods have the lowest consumer participation rates under 10%. Many times, consumers of underground goods bundle similar risk related goods. This relationship is depicted in Figure 1.1.

Low risk underground goods: pirated and stolen goods

Low risk goods include pirated music, software, movies, cable/internet service, and the purchase of stolen merchandise and counterfeit goods. A review of the literature in these areas follows. In the US, the penalties for knowingly and willfully participating in the unlawful consumption of pirated copyr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Modeling Off the Books Consumption

- 3 Informal Consumption

- 4 Underground Consumption

- 5 Conclusion

- Statistical Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index