eBook - ePub

Patriots Against Fashion

Clothing and Nationalism in Europe's Age of Revolutions

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

During the era of the French revolution, patriots across Europe tried to introduce a national uniform. This book, the first comparative study of national uniform schemes, discusses case studies from Austria, Bulgaria, England, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Turkey the United States, and Wales.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Patriots Against Fashion by A. Maxwell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Fashion as a Social Problem

What makes mankind a pack of fools,

And with a tyrant’s scepter rules

The herd as though they were but mules?

“The Fashion.”

– Charles Hickling (1861).1

Sartorial nationalism emerged from anxieties about fashion. From the seventeenth to the twentieth century, European patriots saw fashion as a threat. Understanding sartorial nationalism therefore requires an introduction to what Anne Hollander has called “Anti-fashion.”2 Throughout this book, we will see that the cultural prejudices expressed in anti-fashion rhetoric correspond to exclusions in national concepts. Though social privilege permeates anti-fashion rhetoric, the main theme is sexism.

Anti-fashion, by definition, is an attitude of rejection. At its simplest level, anti-fashion entailed the rejection of particular fashionable garments. Every new fashion trend produces new styles: something will eventually offend individual taste.

Yet large segments of the European public rejected not only this or that particular fashion, but fashionable clothing as such. Authors across Europe denounced fashion as ugly, immoral, expensive, dangerous, and ridiculous. Even fashion magazines disdained fashion: in 1808, the first issue of the Allgemeine Moden-Zeitung [General Fashion Magazine] declared that “there is nothing so ridiculous that it has not once been in fashion.”3 Some Europeans enjoyed fashion, of course, but sartorial nationalism arose from the critique and denunciation of fashion, not its celebration. What, then, did fashion’s detractors find so objectionable?

Anti-fashion proves diverse and no taxonomy of anti-fashion can be precise. The various sorts of anti-fashion do not form mutually exclusive schools, but rather recurring tropes that often reinforced each other. Two schools of anti-fashion, however, contributed little to sartorial nationalism, and will thus be dispensed with briefly.

Firstly, what might be called “aesthetic anti-fashion” sought more beautiful clothes. Several artists and fashion designers judged existing clothing tasteless and ugly, and wrote aesthetic manifestos “against fashion,” to borrow the title of Radu Stern’s anthology.4 Belgian architect Henry van de Velde’s 1900 essay on “The Artistic Improvement of Women’s Clothing,” for example, confessed that he “wanted solely to dress women in the smartest possible way” and thus rebelled “against fashion and its representatives.”5 Oscar Wilde similarly hoped that “the costume of the future in England, if it is founded on the true laws of freedom, comfort and adaptability to circumstances,” would be “most beautiful … because beauty is the sign always of the rightness of principles.”6 English architect E.W. Godwin sought to replace “the many gross absurdities which mark the conventionalities of our present costume.”7 Artists and craftspeople, in conversation with each other, developed sophisticated critiques of fashion; their sartorial aesthetics reflect broader trends in art history. Aesthetic anti-fashion is so voluminous that, as Elizabeth Wilson observed, “the serious study of fashion has traditionally been a branch of art history.”8

Aesthetic anti-fashion activists, however, had little impact on sartorial nationalism, because they rarely formulated their critique in national terms. Italian futurists, the primary exception to this rule, combined aesthetic sensibilities with intense patriotism, but most aesthetic critiques of fashion made no reference to imagined national communities. Sartorial patriots routinely invoked aesthetic language, attacking fashion as ugly and praising their preferred garments as beautiful, but generally cared little about art for art’s sake. Yet the aesthetic judgments of patriots derived from their political preferences, often with hilarious transparency. Apart from the Italian futurists, therefore, aesthetic critics of fashion contributed little to sartorial nationalism.

Secondly, what might be called “feminist antifashion” attacked fashionable clothing as a constraint on women’s freedom. Feminist or proto-feminist dress reformers wanted to liberate women from inconvenient clothing, which they associated with social oppression. The infamous bloomers, for example, sought to replace bustled skirts with baggy pants to facilitate women’s freedom of movement. Myra Macdonald’s study of feminist attitudes toward fashion concluded that “early feminist reactions to fashion were overtly hostile.”9 Patrica Ober concluded of subsequent reform schemes that “the discourse of reform dress was simultaneously a discourse about the bodily autonomy of women.”10

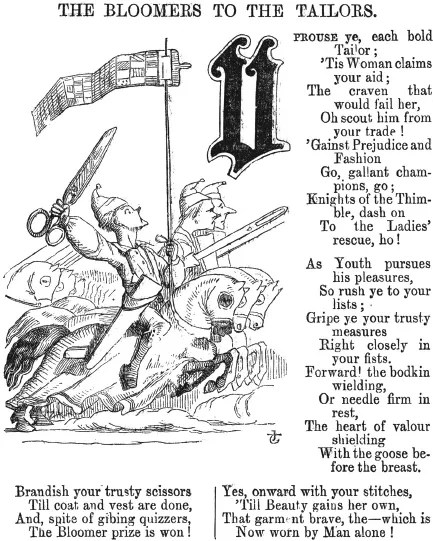

Figure 1.1 Bloomerism as Crusade (1851)11

Feminist anti-fashion emerged from a political agenda, and as such frequently inspired political metaphors. English reformer Ada Ballin compared dress reform to military conflict in her 1885 The Science of Dress in Theory and Practice:

What we want is reform, not revolution … the battle for dress reform is at the present time being very vigorously fought but the soldiers of the rebel camp have unfortunately adopted a mistaken plan of falling upon the enemy just where he, or rather she, is strongest.12

Ballin’s metaphors recall a cartoon from the British satirical magazine Punch that mockingly compared bloomerism to medieval warfare: chivalrous tailor-knights fought against Fashion on behalf of womankind (see Figure 1.1).

Dress reform formed a prolific school of European anti-fashion, and several scholars have discussed feminist or proto-feminist attitudes toward fashion across Europe.13 Feminist anti-fashion, with its political consciousness, resembled sartorial nationalism more than aesthetic anti-fashion. Nevertheless, feminist campaigners often took an internationalist approach. Most importantly, however, hardly any sartorial patriots wrote from feminist motives.

Neither aesthetic anti-fashion nor feminist anti-fashion held much appeal for sartorial nationalists. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, most Europeans were neither aesthetes nor suffragettes. Of course, sartorial patriots as such were hardly a mass movement. Most Europeans were still rural peasants up until the twentieth century, and clothing reform schemes appeal primarily to urban busybodies. Nevertheless, sartorial patriotism rested not on the anti-fashion of aesthetes and suffragettes, but of patriots. How, then, did fashion offend the sensibilities of government officials, lesser nobles, merchants, craftspeople, and other petty bourgeois?

Bourgeois Anti-Fashion

Anti-fashion in the middle classes arose primarily from economic motives. Wealthy aristocrats used expensive and fashionable clothing to show their status; the poor struggled to clothe themselves at all. As members of the middle classes struggled to maintain a respectable appearance however, expensive fashions posed a significant economic burden. Fashion posed the greatest economic threat to those social classes responsible for generating nationalism.

Fear of sartorial expenditure may seem miserly to modern readers, who may not realize how dramatically the relative cost of clothing has declined over recent centuries. Today, for example, Europeans typically discard their old clothes, but before the twentieth century used clothing was sufficiently valuable to pawn, sell, or inherit. One study noted that when the Earl of Leicester purchased various cloaks and doublets in the late sixteenth century, the average individual cost of each garment exceeded the cost of Shakespeare’s Stratford house.14 Another has measured the cost of fine fabrics in fifteenth-century Florence in terms of an annual subsistence income for a family of four.15 Even at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the dark green uniforms of Russian state officials cost half their annual salary, a calculation that omits the cost of a winter coat.16 Mass production made clothes widely available by the mid-twentieth century, but during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, new clothing implied expense.

The fickle caprices of fashion compounded the cost of respectable clothing. Replacing old and threadbare clothing posed a heavy burden on a family, but replacing serviceable clothes simply because they had fallen from style was ruinous. Why should one have to buy a new coat, particularly if a favorite coat still fit and pleased?

Middle-class commentators, in short, hated spending money on new fashions. Consider how Austrian journalist I.F. Castell described the social humiliations resulting from “A New Jacket”:

I go out with a new coat and meet a friend, and he pinches me. When I ask him why he does this, he answers me “so that the tailor will come out!” A second humorous companion ... presses his hands together in admiration and says “Oh! What a beautiful new coat! Has it been paid for?” The third demands that I give him an expense account, how much the cloth cost, and he finds it very pretty and fine, but tells me that he bought one prettier and finer on sale. A fourth finds some fault with the cut and recommends his tailor to me. A fifth tells me that the cloth will lose its color, however nice it is now.17

Castell complained that both beggars and his girlfriend demanded more money, yet found that “the most annoying of these calamities is that people wonder, and even ask me, if I am looking for a new lover.”18 Social annoyances also affected women. English author Leigh Hunt disliked her new hats nearly as much as Castell disliked his new coats. “Maria twitches one this way, and Sophia that, and Caroline that, and Catharine t’other. We have the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Clothing and Nationalism Studies

- 1 Fashion as a Social Problem

- 2 The Tyranny of Queen Fashion

- 3 The Sumptuary Mentality

- 4 The Discovery of the Uniform

- 5 Absolutist National Uniforms

- 6 Democratic National Uniforms

- 7 Minimal National Uniforms

- 8 Folk Costumes as National Uniforms

- 9 National Fashionism: Queen Fashion as Patriot

- 10 Haute Couture and National Textiles

- Notes

- Index