eBook - ePub

Foreign Direct Investment, Governance, and the Environment in China

Regional Dimensions

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book links the environment and corruption with China's large inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI). It investigates the effects of economic development and foreign investment on pollution in China; the effects of corruption and governance quality on FDI location choice in China.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Foreign Direct Investment, Governance, and the Environment in China by J. Zhang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Environment & Energy Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

Environmental pollution and corruption have been inseparable twin evils in modern day China. The immediate motivation for this book is to link the environment and corruption with large inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) to China. It investigates the effects of economic development and foreign investment on pollution in China; the effects of corruption and governance quality on FDI location choice in China; and the relationship between environmental regulation stringency and FDI, as well as the role corruption plays in this relationship.

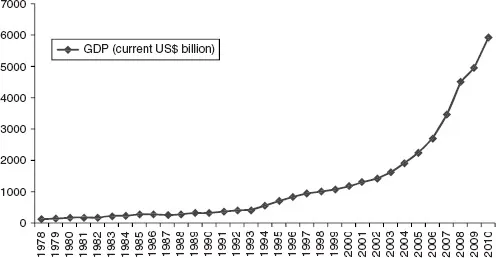

Since 1978 the Chinese government has been reforming its economy from a centrally planned to a market oriented economy, known as socialism with Chinese characteristics. The result of this dramatic transformation has been the generation of wealth on a previously unimagined scale and the removal of millions from absolute poverty, bringing the poverty rate down from 84 per cent in 1981 to 13 per cent in 2008 (World Bank).1 China is the fastest growing country with a consistent annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate above 8 per cent. By the end of 2010, China had overtaken Japan as the second largest economy in the world when measured by nominal GDP (RMB 40.12 trillion, or $5.93 trillion, see Figure 1.1 for the nominal GDP growth of China from 1978 to 2010).2 Removing the impact of inflation, China’s real GDP in 2010 was 20 times as much as that in 1978. The nominal per capita GDP has also increased from RMB 381 to RMB 29,992 (about $4,430), which means a growth of 14.7 times in real terms. This rapid growth has been drawing worldwide attention to China, including from academics in a number of research areas.

Figure 1.1 China’s nominal GDP 1978–2010

Source: World Development Indicators database, The World Bank.

Much of China’s success has been driven by a tremendous growth in exports coupled with equally impressive increases in FDI. According to statistics from China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the value of China’s exports grew by an average of 14.7 per cent a year between 1980 and 2000 and by 27.3 per cent a year between joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 and the world financial crisis in 2008. At the end of 2010 China’s global trade exceeded $2.97 trillion, with exports of $1.58 trillion. After 2010 China surpassed Germany as the world’s largest exporting nation and was the second largest importer after the United States (US). In addition, China’s trade surplus was stable at around $30 billion between 1999 and 2004 but surged rapidly afterwards (varying between $102 billion and $298 billion). In terms of FDI, by 2010 China’s inward FDI flows had reached $105.7 billion, up from an average of $30.10 billion between 1990 and 2000. FDI stock has increased similarly, rising from $20.69 billion in 1990 to $1048.38 billion in 2010.

The Chinese government launched a range of policies to encourage FDI inflows. In 1979, the government introduced legislation and regulations designed to encourage foreigners to invest in high priority sectors and regions. The government eliminated restrictions and implemented permissive policies in the early 1980s. It established Special Economic Zones in 1980 and then opened up coastal cities and development regions in coastal provinces in the mid-1980s. More favourable regulations and treatment have been used to encourage FDI inflows to these regions. In the 1990s, the policies began to promote high-tech and capital intensive FDI projects in accordance with domestic industrial objectives. Preferential tax treatments were granted for investment in selected economic zones or in projects encouraged by the government, such as energy, communications and transport. These preferential policies have resulted in an overwhelming concentration of FDI and rapid economic development in the east. Spillover effects from coastal to inland provinces are limited and therefore the gap in regional development has widened.

Rapid export driven economic growth enhanced by large investment inflows from abroad has come at a cost. A harmful by-product of globalization has been increased pollution. The State Environmental Protection Administration (predecessor to the Ministry of Environmental Protection) reported that two-thirds of Chinese cities are considered polluted according to the air quality data. Respiratory and heart diseases related to air pollution are the leading causes of death in China. Almost all the nation’s rivers are polluted to some degree and half the population lacks access to clean water. Water scarcity occurs most in northern China and acid rain falls on 30 per cent of the country. The World Bank estimated that pollution costs about 8–12 per cent of China’s GDP each year. Environmental degradation and the increase in poor health are all signs that China’s current growth path is unsustainable.3

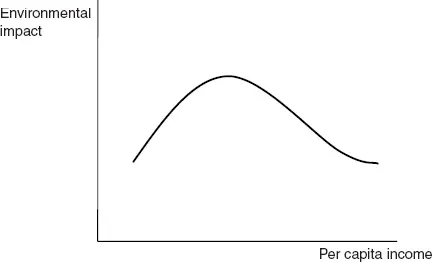

There have been numerous theoretical and empirical studies that examined the relationship between economic growth and various indicators of environmental degradation. The aim of this research is to examine the existence of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC), initially developed by Grossman and Krueger (1991). The hypothesis of EKC indicates that the environmental impact of economic growth initially increases, reaches a peak and then falls, as illustrated in Figure 1.2. In addition, some researchers have started to use empirical methods to examine the effects of FDI on environmental quality, especially in developing countries. However, the majority of studies on both the environmental effects of economic growth and FDI, are cross-country analyses and the results are often inconsistent.

Therefore, in the case of China, the following questions are worthy of consideration. Does the EKC hold for particular pollutants? If it does, what is the threshold income level and how many regions have passed it? As an important driving force for economic growth in China, does FDI benefit or harm environmental quality? These questions have attracted relatively little research; what research there has been has used different datasets and methodologies, with mixed results.

Figure 1.2 Environmental kuznets curve

The huge amount of FDI inflow and its unbalanced geographical distribution has attracted several studies investigating the determinants of FDI location choice in China (see for example Wei et al., 1999; Coughlin and Segev, 2000; Cheng and Kwan, 2000; Amiti and Smarzynska-Javorcik, 2008). In addition to preferential policies, many factors may have affected where foreign investors located their production facilities within China, such as labour costs, potential market size, market access, supplier access, infrastructure, productivity, education level, location, and spatial dependence. However, these studies all omitted certain structural determinants of FDI, including environmental regulation stringency and government quality.

Some environmental economists and environmentalists claim that firms in developed countries may relocate their ‘dirty’ industries to developing countries to take advantage of less stringent environmental regulations (see for example Pearson, 1987; Dean, 1992; Copeland and Taylor, 1994). Such a point of view is known as the pollution haven hypothesis (PHH).

In China, the legal system has lagged far behind overall economic development. Although it has established a comprehensive environmental regulatory framework with a range of laws, regulations and standards, the strength and enforcement of the regulations are much weaker than in developed countries. An important issue in the enforcement of environmental regulations is that of the government itself violating the law. Some local governments protect polluting enterprises in the name of local interest. Situations like land appropriation, excessive mining and the failure to carry out environmental impact assessments continue due to the lack of the environmental awareness among local government officials. Environmental enforcement also suffers from a lack of public participation and social supervision, as well as low awareness amongst citizens (Ma, 2007). The differences in performance between local governments and the behaviour of the public means that environmental stringency varies among the regions.

Multinational corporations (MNCs) could be attracted by the weak environmental regulations in China. Ma Jun, director of the non-governmental Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), announced in August 2007 that since 2004 over a hundred multinational corporations had been punished by the government for their violation of the environmental laws and regulations on water pollution (People.com.cn, 2007; 21cbh.com, 2008). In January 2008 this figure increased to 260 corporations for water pollution and more than fifty corporations for air pollution (Xinhuanet, 2008). The exposed companies included subsidiaries of world renowned corporations such as American Standard, Panasonic, Pepsi, Nestlé, 3M, Whirlpool, Bosch, Carlsberg, Samsung, Nissin Foods and Kao. These corporations are mostly from Japan, US and Europe. One third of their polluting subsidiaries are located in Shanghai, and others scattered over the country. Liu (2006) reported that according to Lo Sze Ping, campaign director of Greenpeace China, the words of multinationals are often better than their deeds. Multinationals are more willing to invest in public relations than in actually cleaning up the manufacturing process. Local governments seek to attract more FDI and hence do not take strict measures to address the pollution from multinational corporations. Lo also observes that since multinational corporations typically perform better environmentally than domestic enterprises, their activities do not attract the attention of the environmental authorities, and hence avoid the supervision.

Therefore, the regional differences in environmental stringency may have a significant impact on the choice of FDI location in China, that is to say, an intra-country pollution haven effect may exist. Previous empirical studies have adopted different approaches to investigating the PHH (see for example Levinson, 1996a, 1996b; List and Co, 2000; Keller and Levinson, 2002; Xing and Kolstad, 2002; Eskeland and Harrison, 2003; Fredriksson et al., 2003; Dean et al., 2005; Smarzynska-Javorcik and Wei, 2005). The results are mixed and do not provide robust evidence to support the existence of PHH. However, these studies have several methodological weaknesses and are mostly centred on US data, a few studies look at developing countries and only Dean et al. (2005) look at China. Therefore, by addressing the weaknesses of previous studies, this book makes some contribution to the literature on PHH.

Rapid economic growth combine with the slow development of the legal system has resulted in a serious social problem in China, corruption. The transition to a market-based economy has resulted in considerable changes in how firms operate within the new commercial environment. The huge increase in opportunities in the private sector, combined with the traditional power of local and national officials, led to a proliferation of corruption at all levels of the Chinese economy. Corruption has been recognized as an emerging challenge to China’s economic and social reforms.

Corruption is widely recognized as a deterrent to foreign investment but is only considered in a few empirical studies on a cross-country basis (see for example Wheeler and Mody, 1992; Hines, 1995; Wei, 2000; Smarzynska-Javorcik and Wei, 2000). Although China has received a high volume of foreign capital, corruption has deterred FDI inflows, especially those from Europe and the US. Wei (1997) notes that FDI from the ten largest s ce countries in the world, all of them members of Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), accounts for a relatively small portion of the total FDI going to China, because investors from the major source countries prefer to go to less corrupt countries. Similarly, the corruptibility of local government in China may affect the location of FDI. Moreover, corruption should not be considered in isolation and is strongly correlated with the quality of government (see Globerman and Shapiro, 2002, 2003; Globerman et al., 2006; Fan et al., 2007), which makes government quality another important determinant of FDI inflows. Therefore, this book is the first to examine the effects of inter-regional differences in corruption and government quality on FDI location choice within a large developing country.

Corruption is also associated with environmental regulations. A common limitation in pollution haven studies is that they only consider the impact of environmental regulations on FDI, few have considered the endogeneity of environmental regulations. This book is the first to consider that environmental stringency may be influenced by both corruption and the level of FDI.

1.2 Structure of the book

Combining various aspects within the broad area of FDI, governance and the environment, this book is structured as follows. Chapter 1 is the introduction, which outlines the background in China, research questions and a brief analytical framework of this book. Part I of the book includes four substantial chapters looking at the effects of economic development and FDI on the environment in China. Chapter 2 examines China’s economic growth and the nature and development of inward FDI from its opening up in 1978. Chapter 3 examines China’s natural environment and its environmental pollution. Particular attention is paid to the pollution of water, air and solid waste pollution, and the cost of pollution. Chapter 4 reviews the theoretical and empirical research on EKC and the impact of FDI on the environment, particularly the research using Chinese data. Chapter 5 examines the relationship between economic growth and a range of industrial pollution emissions in China using data on 112 major cities between 2001 and 2004. After separating out investment from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan from the investment of other foreign economies, we also observe the environmental effects of different ownership groups of investment. The results provide some evidence that economic growth induces more pollution at current income levels in China, and that the environmental effects vary across investment groups.

Part II of this book contains three chapters that consider environmental regulatory stringency as a structural determinant of FDI. Chapter 6 introduces China’s environmental protection legal framework and its implementation. It shows regional differences in terms of investment in environmental protection and analyses the reas...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- Part I The Effects of Growth and FDI on the Environment in China

- Part II The Effect of Environmental Regulations on FDI in China

- Part III Corruption, Government, FDI, and the Environment in China

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index