eBook - ePub

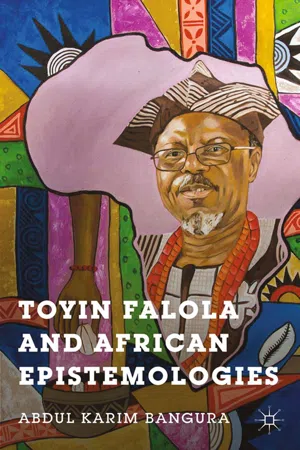

Toyin Falola and African Epistemologies

A. Bangura

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Toyin Falola and African Epistemologies

A. Bangura

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

While there are five important festschriften on Toyin Falola and his work, this book fulfills the need for a single-authored volume that can be useful as a textbook. I develop clearly articulated rubrics and overarching concepts as the foundational basis for analyzing Falola's work.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Toyin Falola and African Epistemologies an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Toyin Falola and African Epistemologies by A. Bangura in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Sociologia delle religioni. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Scienze socialiSubtopic

Sociologia delle religioniP A R T I

Africa in the Configurations of Knowledge

C H A P T E R T W O

African-Centered Conceptualization

Introduction

The African-centered conceptualizations in Toyin Falola’s work are important because most of the concepts used in works dealing with Africa or African issues, as I have argued elsewhere, employ Eurocentric concepts that often do not capture the essence of the phenomena discussed. Calling a thing by its precise name is the beginning of understanding because it is the key to the procedure that allows the mind to grasp reality and its many relationships. It makes a great deal of difference whether one believes an illness is caused by an evil spirit or by bacteria on a binge. The concept of bacteria is part of a system of concepts connected to a powerful repertory of treatments, such as antibiotics. Naming is a process that gives the namer great power.1

As I also have stated, old movies about Africans often have an episode featuring a confrontation between the local “medicine man” or “witchdoctor” and the Western “doctor” who triumphs for modern science by saving the chief or his child. The cultural agreements supporting the “medicine man” are shattered by the scientist with a microscope. Sadly, for the children of modern medicine, it turns out that there were a few tricks in the medicine man’s bag that were ignored or lost in the euphoria of such a “victory” for science. Also, one notes the arrogance with which many of the cultural arrangements expressed in African languages were undermined through the supposition of superiority by conquering powers. Capturing meaning in a language is a profound and subtle process, indeed.2 I must add here that the theoretical discussions in the two sections that follow appear in the two works cited above.3

The General Import of Concepts

Thinking involves the use of language. Language itself is a system of communication composed of symbols and a set of rules permitting various combinations of these symbols. One of the most significant symbols in a language is the concept. Social scientists Chava Frankfort-Nachmias and David Nachmias define a concept as “an abstraction—a symbol—a representation of an object or one of its properties, or of a behavioral phenomenon.”4 Concepts are generally defined as abstract ideas or mental symbols that are typically associated with corresponding representations in languages or symbologies that denote all of the objects in given categories or classes of entities, events, phenomena, or relationships among them. Concepts are said to be abstract because they omit the differences of the things in their extensions, treating them as if they are identical; they are said to be universal because they apply to everything in their extensions. Concepts are also characterized as the basic elements of propositions, much the same way words are the basic semantic elements of sentences.

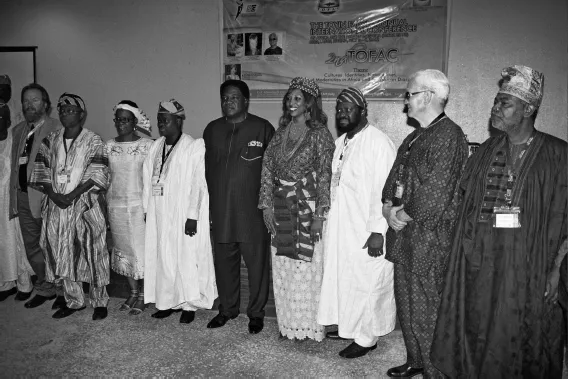

Image 2.1 Speakers and dignitaries at the 2012 Second International Toyin Falola Annual Conference (TOFAC) in Lagos, July 23, 2012. In the middle is Chief Duke, Nigeria’s federal minister for culture. Photograph from Toyin Falola’s collection.

Rather than agents of meaning, concepts are bearers of meaning. Consequently, concepts are arbitrary. For example, the concept of “tree” can be expressed as tree in English, shajar in Arabic, mti in Kiswahili, kənt in Temne, àrbol in Spanish, albero in Italian, arbre in French, árvore in Portuguese, дерево in Russian, and baum in German. The fact that concepts are arbitrary, that is, independent of language, makes translation possible; words in various languages have identical meaning because they express one and the same concept.

For scientific purposes, social scientists Kenneth Hoover and Todd Donovan posit that concepts are “(1) tentative, (2) based on agreement, and (3) useful only to the degree that they capture or isolate some significant and definable item in reality.”5 Thought and theory develop through the linking of concepts, and science is a way of checking on the formulation of concepts and testing the possible linkages between them through references to observable phenomena.

The scientific function of concepts, according to Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, is fourfold. First, concepts are the foundation of communication. Without a set of agreed-upon concepts, scientists could not communicate their findings or replicate one another’s studies. Second, concepts introduce perspective, that is, a way of looking at empirical phenomena. Concepts enable scientists to relate to some aspect of reality and identify it as a quality common to different examples of the phenomena in the real world. Third, concepts allow scientists to classify: to structure, characterize, order, and generalize their experiences and observations. Finally, scientists use concepts to serve as components of theories and, therefore, of explanations and predictions. Consequently, concepts are the most critical elements in any theory because they define its content and attributes.6

The Essence of Concepts in Communication

The correct or objective use of concepts is essential for successful communication because it involves two or more participants in an interaction who must share similar meanings of various concepts.7 For linguists, the essence of concepts in communication rests on the notion of conceptual dependency, defined by Gillian Brown and George Yule as the relationship between attitudes and behavior; however, when applied to understanding discourse, it incorporates a particular analysis of language.8 Roger Schank sets out to represent the meanings of sentences in conceptual terms by providing a conceptual dependency network he terms a C-diagram, a network that contains concepts that enter into relations he describes as dependencies. He also provides a very elaborate, but manageable, system of semantic primitives for concepts, and he labels arrows for dependencies, a process that I will not describe in this chapter, as it is too big a topic for the study at hand.9 Instead, I will simply consider one of Schank’s sentences and his nondiagrammatic version of the conceptualization underlying that sentence in the same manner as Brown and Yule do.

1.John ate the ice cream with a spoon.

2.John ingested the ice cream by transing the ice cream on a spoon to his mouth.

(The term “transing” is used here to mean “physically transferring.”)10

One benefit of Schank’s approach is quite obvious. In his conceptual version (2) of the sentence (1), he represents a part of our comprehension of the sentence that is not explicit in the first sentence (1), that the action described in (1) was made possible by getting the ice cream and his mouth in contact with each other. In this way, Schank incorporates an aspect of our knowledge of the world in his conceptual version of our understanding of sentence (1) that would not be possible if his analysis operated with only the syntactic and lexical elements in the sentence.

In a development of the conceptual analysis of sentences, Chris Riesbeck and Roger Schank describe how our comprehension of what we read or hear is very much based on expectations. Stated differently, when we read example (3), we have very strong expectations about what, conceptually, will be in the x position in sentence (4).

3.John’s car crashed into a guardrail.

4.When the ambulance came, it took John to the x.11

Riesbeck and Schank point out that our expectations are conceptual rather than lexical and that different lexical realizations in the x position (e.g., hospital, doctor, medical center, and the like) will all fit our expectations. Brown and Yule add that evidence that people are “expectation-based parsers” of texts hinges on the fact that we can make mistakes in our predictions of what will come next.12

John Lyons introduces the notion of conceptual fields by relying on Jost Trier’s general definition of “fields”: “fields are living realities that intermediate between individual words and the totality of the vocabulary; as parts of a whole they share with words the property of being integrated in a larger structure (sich ergleiden) and with the vocabulary the property of being structured in terms of smaller units (sich ausgliedern).”13 Lyons illustrates the notion of the conceptual field by employing the continuum of color, prior to its determination by particular languages. According to him, color terminology provides a particularly good illustration of differences in the lexical structure of different language systems. He notes that there are problems in recognizing a conceptual area; in this case, a psycho-physical definable field of color is neutral with respect to different systems of categorization. He also notes that if we are to accept the proposition that it is reasonable to think of the continuum, or substance, of color in this manner, then different languages and different synchronic states of what may be regarded diachronically as the same language evolving through time can be compared with respect to the way they give structure to, or articulate (gliedern), the continuum by lexicalizing certain conceptual (or psycho-physical) distinctions. This continuum can then give lexical recognition to greater or less areas within it. In considering color as a continuum, the substance of color is—distinct from “area” and “field”—a conceptual area; it becomes a conceptual field by virtue of its structural organization, or articulation, by particular language systems. He then concludes that the set of lexemes in any one language system that cover the conceptual area and, by means of the relations of sense that operate between them, gives structure to the language system as a lexical field. Each lexeme will cover a certain conceptual area, which may in turn be structured as a field by another set of lexemes (as the area covered by “red” in English is structured by “scarlet,” “crimson,” “vermillion,” etc.). Thus, the sense of a lexeme is a conceptual area within a conceptual field, and any conceptual area that is associated with a lexeme, as its sense, is a concept.14

Meanings of Major African-Centered Concepts in Falola’s Work

The following are concise and precise descriptions of major African-centered concepts in Falola’s work. They are presented in alphabetical order. As noted earlier, no attempt is made to discuss those writers who have misrepresented African phenomena by their uses of Eurocentric concepts.

Ajele refers to a consul of the governor placed by an oba (king) in a conquered place.15 Ajo, Esusu, and Iranlowo refer to interrelated money-lending or credit schemes. Ajo and Esusu provided credit on generous terms to members of rotating savings and credit associations; they were so generous that neither collateral nor interest was required. The esusu involved a number of people who agreed to save money for a limited time period. In certain arrangements, one participant served as a “banker” for the duration of the savings. At the end of the period, the “banker” would return each participant’s savings. In other arrangements, participants agreed to contribute the same amount of money at the end of a week or a month. The total sum collected was given to each person on a rotational basis. In esusu, participants did not pay interest nor were fees deducted. Participants were morally obligated to complete the contributions to which they agreed. Should a participant die, his or her savings were given to a relative.16

The ajo was similar to the esusu in that participants had to know one another well. The organization of ajo varied. Sometimes, participants decided on the amount and the duration of savings to be collected by a chosen leader. At the end of the designated time, each participant’s contributions were returned. In other arrangements, each member contributed what he or she could afford and could collect his or her savings at any time when the money was needed. Participants in an ajo did not receive interest for their contributions.17

Both esusu and ajo had to be substantially reformed to meet the demands of the con...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- One An Emerging Biography

- Part I Africa in the Configurations of Knowledge

- Part II The Yoruba in the Configurations of Knowledge

- Part III The Value of Knowledge: Policies and Politics

- Appendix: Notation Conventions

- List of Works by Toyin Falola

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Citation styles for Toyin Falola and African Epistemologies

APA 6 Citation

Bangura, A. (2015). Toyin Falola and African Epistemologies ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan US. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3482322/toyin-falola-and-african-epistemologies-pdf (Original work published 2015)

Chicago Citation

Bangura, A. (2015) 2015. Toyin Falola and African Epistemologies. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan US. https://www.perlego.com/book/3482322/toyin-falola-and-african-epistemologies-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Bangura, A. (2015) Toyin Falola and African Epistemologies. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan US. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3482322/toyin-falola-and-african-epistemologies-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Bangura, A. Toyin Falola and African Epistemologies. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan US, 2015. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.