This is a book about how we raise our children, or more precisely, it is a book about what we think we are doing when we raise our children. The way we understand this most vital of human tasks is shaped by our fundamental understandings of what kind of creatures human beings are, how we live with one another in society and how, via the movement from one generation to the next, human history is moved along from the present to the future. Shifts in any of these interrelated conceptualisations have ideological and practical repercussions for what we do to bring the next generation to adulthood. Therefore, by looking closely at the discourse through which changes to the culture and practices of child-rearing are argued for in the domain of politics and public policy, we can deepen our understanding of the particular historical conjuncture in which we currently stand.

There is a long history of advice given to parents to guide them in the task of socialising the next generation (Furedi 2001, 2008; Hardyment 1995; Hendrick 1997; Stearn 2003) but we will look at a new addition, ‘neuroparenting’. Neuroparenting is a way of thinking which claims that ‘we now know’ (by implication, once and for all) how children ought to be raised. The basis for this final achievement of certainty regarding childrearing, which we know has changed dramatically from one historical period to the next and which we are aware still varies greatly across diverse human societies, is said to be discoveries made through neuroscience about the development of the human brain, in particular, during infancy. One neuroparenting proponent, Dr Erin Clabough (2016), aims to raise ‘parental awareness about normal brain development’ because ‘every day is a critical period’ (see www.neuroparent.org).

Readers may not have heard of neuroparenting. This is not surprising, as it is a neologism which so far exists primarily in the branding of a handful of such ‘parenting experts’, whose advice, they claim, is informed by the latest brain research. However, new parents are very likely to have heard ‘brain claims’ about the ‘critical’ significance of what they do in pregnancy and the ‘early years’ of their child’s life for his or her long-term prospects. All of us, parents or not, will have heard about studies showing that breast milk or classical music have brain-boosting properties or that child abuse and neglect have brain-shrinking effects. Anyone working in the public sector, in particular in education, the early years, maternal and child health or social services, will have been told of the proven benefits of ‘early intervention’, which works because it takes advantage of the ‘window of opportunity’ represented by the years 0–5, 0–3, 0–2 or minus 9 months to 1.

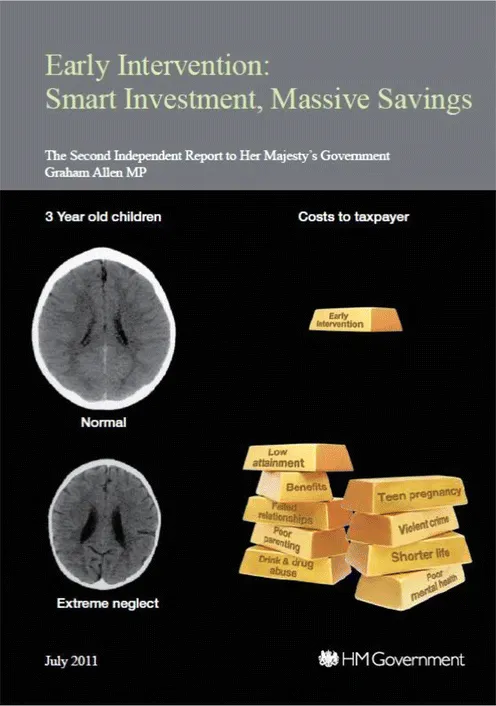

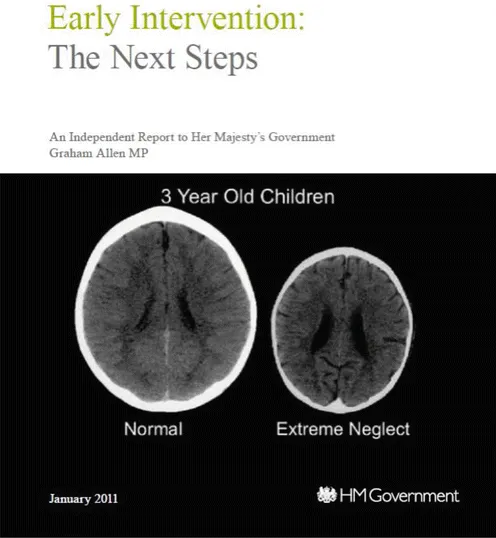

What ‘we now know’ about the infant brain is described using neuro-vocabulary such as neurons, synapses, critical periods, toxic stress and cortisol. The case for urgent action will possibly have been emphasised using an image of two brains, one ‘normal’ the other smaller and containing ‘black holes’, with the explanation given that the normal-sized brain is the product of parental love and the shrivelled one is the product of parental neglect (seen here on the cover of two UK government reports, this image is referred to henceforth as the ‘Perry image’ owing to its source, neuroparenting advocate Professor Bruce D. Perry) (Fig.

1.1).

Babies’ brains are just one element in contemporary parenting discourse, but the underlying message of neuroparenting, that the early years ‘last forever’ and therefore deserve much greater parental and societal attention, is ubiquitous. Concern for babies’ brains has entered the mainstream of British politics over the past decade. As this book was being edited, the British Prime Minister (PM) David Cameron gave a speech entitled ‘Life Chances’, the rhetorical cornerstone of which was brain claiming: ‘Thanks to the advent of functional MRI scanners, neuroscientists and biologists say they have learnt more about how the brain works in the last 10 years than in the rest of human history put together.’ He went on to argue, ‘when neuroscience shows us the pivotal importance of the first few years of life in determining the adults we become, we must think much more radically about improving family life and the early years’. Drawing on the lexicon of neuro-buzzwords, he justified the provision of parenting classes for all UK parents on the basis that ‘one critical finding is that the vast majority of the synapses, the billions of connections that carry information through our brains, develop in the first 2 years. Destinies can be altered for good or ill in this window of opportunity’ (Cameron 2016).

The ‘Life Chances’ speech is the clearest expression yet in mainstream British politics of a ‘brainified’ argument for government action. Many on social media reacted angrily, objecting that David Cameron was in no position to be dishing out parenting advice, that he was just a privileged ‘toff’ who spent much of his own childhood away from his parents at boarding school. Numerous commentators mockingly reminded us that the PM and his wife had once driven off after a pub lunch without their eight year-old daughter. A few took the speech’s references to the importance of marriage and the problem of absent dads as evidence of the ‘same old’ Tory-moralising, while others concluded that Cameron was blaming parents for failing to cope with the cuts to welfare and services that his government was implementing. But what nobody (with the exception of Lee 2016) reflected on was just how remarkable (and absurd) it was to hear the British PM propose that the best solution to the very grown-up problems of economic and social malaise was the project of getting British mothers and fathers to engage in more of ‘the baby talk, the silly faces, the chatter even when we know they can’t answer back’ through which ‘mums and dads literally build babies’ brains’, as though what he called ‘the biological power of love, trust and security’ would then automatically emanate from individual babies to the structures of British society (Cameron 2016).

This book therefore conceptualises neuroparenting as a political argument. The rhetoric of babies’ brains is deployed to challenge the fundamental rights and responsibilities which have shaped British family life for the past 100 years or more, in particular, the general presumption that parents know best when it comes to caring for babies and getting toddlers to school age. The pre-school years have traditionally been a time when parents, and mothers in particular, were entrusted with almost exclusive care of the child and were left to perform this task amongst themselves, making use of wider relationships with family, friends and community. Recourse to medical advice and socialised child care was on the parent’s terms and heavy state intervention to rescue the child occurred only when things went very badly wrong. But the neuroparenting argument reconstructs this period of informal, privatised care as being of national importance and therefore as everybody’s business. Now considered to be precariously full of risks and yet more important than any other period in the life course, the early years are, as David Cameron claimed, said to determine our ‘destinies’ for ‘good or ill’. The neuroparenting argument that ‘the first years last for ever’ has grown in strength in recent years as it has been repeated in many public forums: in parliamentary inquiries and debates, on government committees and in published reports, in think-tank documents and during symposiums, at guest lectures by international neuroparenting ‘celebrities’ and in the pages of national newspapers. In the rest of the book, we refer to the promotion of neuroparenting within the policy domain in a number of ways. We make use of the concept ‘the first three years movement’ (Thornton 2011a, b) to describe its growing influence and will also use, interchangeably, the terms ‘0–3’, the ‘early years’ or the ‘parenting support’ agenda.

Normalising Parent Training

While David Cameron’s speech provides the most explicit evidence yet that the neuroparenting agenda has been adopted by UK policy-makers, it should be understood as the result of a much longer process of political change. The fact that when a Conservative PM confidently called for all parents to offer themselves up for state-provided training there were only a few limp cries of ‘it’s the nanny state gone mad’ in response, indicates the extent to which the argument for ending the presumption of parental competence and the right to a private family life has already been won amongst the political class at least. The argument that the boundaries around the family need to be weakened in the name of children’s welfare has been going on since at least the mid-1990s. As time has gone on, its proponents have become less apologetic and oppositional voices have become almost non-existent. The Liberal-Democrat peer, Baroness Tyler, in the foreword to a parliamentary report on parenting and social mobility, indicates that politicians are very aware that the parenting support agenda requires a reworking of the presupposition that parents know better than the state when it comes to how they raise their children, when she says, ‘For too long, fear of being criticised for interfering in family life has led politicians and policy makers to shy away from this arena.’ Pre-empting David Cameron by almost a year, she states, ‘The early years and particularly what happens in the home are of utmost importance for a child’s future,’ because, ‘it is parents—not teachers or government—who are ultimately responsible for a child’s development in these early years.’ However, we can see that although parents are held totally responsible for raising the next generation, their capacity to perform this vital task is called into question:

The hope has been that all parents would be able to provide the most appropriate social and emotional development for their children in the pre-school years, which we now know is the vital underpinning for educational attainment and emotional wellbeing, without needing any help and support in doing this critically important job…Yet it is time to change our views about parenting: not all parents know how to be a good parent, not because of lack of skills or bad intentions, but often because of poor information, advice and support…In short it is time to end the ‘last great taboo in public policy’. (Tyler 2015)

While many people might share Baroness Tyler’s concerns regarding the ability of

some parents to raise their children well, it is unlikely that they would be happy for this doubt from on high to be applied to themselves. But the parenting support agenda is a universal one, as David Cameron made clear:

getting parenting and the early years right isn’t just about the hardest-to-reach families, frankly it’s about everyone. We all have to work at it…As we know, they don’t come with a manual and that’s obvious, but is it right that all of us get so little guidance?…We all need more help with this – because it is the most important job we’ll ever have. So I believe we now need to think about ho...