This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Violence in Adolescent Romantic Relationships

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Domestic violence in adolescent romantic relationships is an increasingly important and only recently acknowledged social issue. This book provides conceptual frameworks for the design and evaluation of interventions with a focus on developing evidence based practice, as well as a research, practice and policy agenda for consideration.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Psychology of Violence in Adolescent Romantic Relationships by Erica Bowen,K. Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Personality in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Contextualising Violence and Abuse in Adolescent Romantic Relationships

Introduction

Traditionally, when researchers have examined violence and abuse in intimate or romantic relationships, attention has focused on adult relationships. This is of note, considering that the study of adolescent relationship violence was initiated in the early 1980s, merely a decade or so later than the study of violence in adult relationships. The interest in violent and abusive adolescent relationships has grown exponentially since then. A Google Scholar search using the terms adolescent + ‘dating violence’ returned: 71 papers dated between 1980 and 1990; 751 dated between 1991 and 2000; 4,440 dated between 2001 and 2010; and 3,410 dated between 2011 and March 2014. This intervening time period has seen changes in how young people’s relationships are understood and appraised, and also in how policy has acknowledged and responded to such behaviours in adolescent romantic relationships. Alongside advances in our understanding of the nature, antecedents and consequences of violence and abuse in adolescent romantic relationships, has been an increase in the development of primary and secondary interventions and their evaluation. Given the increase in research activity in this field, and more recent policy focus on this issue it seems prudent to consolidate what we know about violence and abuse in adolescent relationships and how to prevent it; this is the ultimate aim of this book.

To start with then, this chapter serves to introduce readers to the main concepts relevant to the volume. Understanding the nature of adolescence and its associated developmental milestones is important for two main reasons: (1) it will enable an understanding of how conflict, control and abuse may occur within romantic relationships during this period; and (2) it can inform the development of interventions aimed at reducing and preventing these behaviours. Christie and Viner (2005) argue that providing interventions of any kind during adolescence is challenging, not least due to the communication difficulties that arise during this developmental period. Consequently, it is important to understand the characteristics of the developmental backdrop against which relationship violence arises, and intervention efforts are conducted. The aim of this first chapter, therefore, is to provide an overview of what is understood about adolescence and the romantic relationships that occur within this developmental frame, as well as characterising the nature and extent of violence and abuse that occurs within these relationships. Issues of definition and measurement are also evaluated critically. A final consideration is then given to how the phenomenon of relationship violence during adolescence specifically is reflected in public and social policy and the case for why researchers, practitioners and policy makers should be interested in this issue is made.

What is adolescence?

At its most basic and ambiguous, the term ‘adolescence’ is typically understood to refer to the period of development between childhood and adulthood (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002). A more precise definition, based on chronological age, is offered by the World Health Organization (2014) as the period between 10 and 19 years of age with the period between 10 and 14 identified as ‘early adolescence’ (WHO, 2014). Most researchers have typically parsed ‘adolescence’ into three distinct developmental phases: early adolescence (ages 10–13), middle adolescence (ages 14–18) and late adolescence (from 18 to the early 20s; Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Mtzger, 2006). Whereas the transition into adolescence is marked by clear and dramatic biological changes, the transition into adulthood is more sociologically defined by achieving milestones such as family formation, completion of education and entrance into the workforce (Smetana et al., 2006). In their review of the literature Smetana et al. (2006) report that most of the research conducted into adolescence focuses on populations aged between 10 and 18 years. Consequently, ‘adolescence’ will be taken to refer to the developmental period that coincides with the chronological age range of between 10 and 18 years. The literature reviewed in this book will therefore also focus on this period.

Although early theorising regarding the nature of adolescence identified it as a period of considerable developmental turmoil, empirical research refutes this characterisation, with on average only between 5 and 15% of young people experiencing considerable turmoil during adolescence (Richter, 2006). Undoubtedly, adolescence is a time of considerable biological, physical, psychological and social change, but it seems that adolescents themselves are better able to negotiate and navigate these changes than society expects and, more fundamentally, acknowledges. The main universal developmental tasks of adolescence include those relating to puberty and sexual maturation, those related to the evolution of personal and social interests and the attainment of hypothetical and deductive reasoning, and those that relate to the construction of identity and self-concept (Christie & Viner, 2005).

The extent to which relationship violence and abuse have their origin in adolescence is unclear. The successful negotiation and attainment of intimate relationships is a key milestone during this period, and provides the interpersonal context for violence and abuse to occur. However, it is likely that for a proportion of young people who engage in relationship violence and abuse during this period, the developmental seeds of these behaviours are rooted in earlier behavioural problems (Moffitt, 1993). Nevertheless, there is some evidence that biological changes during adolescence, particularly the early timing of puberty, may then increase the likelihood of boys and girls engaging in sensation-seeking and risk-taking behaviours. This includes for girls, inappropriate sexual relationships, which then place them at greater risk of encountering violence and abuse in intimate relationships (Ortega & Sánchez, 2011). Consequently, it is possible that for some, violence and abuse in relationships exists in part due to the influence of biologically-driven decision-making. Potential risk factors and their developmental course are examined in more depth in Chapter 3.

Adolescent romantic relationships

The term ‘romantic relationships’ is typically taken to refer to mutually acknowledged ongoing voluntary interactions and is commonly marked by expressions of affection and perhaps current or anticipated sexual behaviour (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009). The definition applies to all relationships regardless of gender and sexuality. This term is differentiated from ‘romantic experiences’, which refers to a greater range of activities and cognitions which may include relationships, but also behavioural, cognitive and emotional phenomena that do not involve direct experiences with a romantic partner (Collins et al., 2009, p. 632).

Research examining the formation, nature and course of romantic relationships during adolescence has only really flourished since the turn of the twenty-first century (Collins et al., 2009; Smetana et al., 2006), despite the attainment of intimate relationships being acknowledged as a key developmental milestone much earlier (Erikson, 1968). Collins et al. (2009) observe that the incidence of romantic relationships during adolescence is higher than had been assumed, with research suggesting that half of adolescents reporting having a ‘special’ romantic relationship in the past 18 months (Carver, Joyner, & Udry, 2003). Such estimates increase when broader criteria, such as ‘dating’ or ‘going out with someone for at least a month’ are used (Furman & Hand, 2006). However, as might be expected, these rates vary across the different developmental stages within adolescence. Carver et al. (2003) reported that 36% of 13-year-olds, 53% of 15-year-olds and 70% of 17-year-olds reported having had ‘special’ romantic relationships in the previous 18 months. These data indicate, therefore, that by the end of adolescence, a clear majority of young people have engaged in at least one such relationship.

What happens in adolescent romantic relationships?

In one of only two studies to examine the behaviours and activities that adolescents engage in during the course of romantic relationships, Carlson and Rose (2012) examined the association between engaging in activities and relationship satisfaction. The most often identified activities (reported by more than 65% of participants) in dating relationships included: talking in school, going to each other’s houses, listening to music, talking on the telephone, talking about personal things and talking about non-personal things. When associations with relationship satisfaction were examined it was found that a positive association existed for 13 dating behaviours, and that in the vast majority of cases there were no significant interactions with gender or grade. This illustrated that the pattern of associations between activities and satisfaction were broadly similar across age and gender. These findings are important as the inclusion of the younger age group, but lack of age-related findings, challenges the historical view that early adolescent romantic relationships are meaningless (Thorne, 1986).

Research has documented that there is a predictable sequence of sexual and intimate behaviours that occur over time towards adulthood. A progression is made from hugging and holding hands to kissing and touching breasts/genitals over and then under clothes, and further towards more intimate and then coital behaviours, including oral sex and sexual intercourse (Hansen, Paskett, & Carter, 1999; Hansen, Wolkenstein, & Hahn, 1992; Waylen, Ness, McGovern, Wolke, & Low, 2010).

The nature of adolescent dating violence (ADV)

Academic definitions

No uniform academic definition of ADV exists. Typically, the term ‘dating violence’ has been used to describe all forms of violent behaviour that may occur in a dating relationship (Teten, Ball, Valle, Noonan, & Rosenbluth, 2009), including: emotional (including psychological/verbal), physical and sexual. However, such behaviours are defined using a range of terms (for example, teen dating violence; relationship abuse; intimate partner violence; dating abuse; domestic abuse and domestic violence) that vary in their comprehensiveness (Glass et al., 2003). Consequently, researchers and policy makers are challenged by the lack of universal definition for ADV. Definitions of ADV are quite broad and do attempt to encapsulate all of the characteristics of ADV and its contemporary technological context. For example, Mulford and Blachman-Demner (2013) define ADV as:

a range of abusive behaviours that preteens, adolescents and young adults experience in the context of a past or present romantic or dating relationship. The behaviours include physical and sexual violence, stalking and psychological abuse, which includes control and coercion. Abuse may be experienced in person or via technology. (p. 756)

That variation in terminology exists means that it is important for clear definitions to be provided by researchers and policy makers so that it is possible to meaningfully synthesise findings.

Definitions in practice

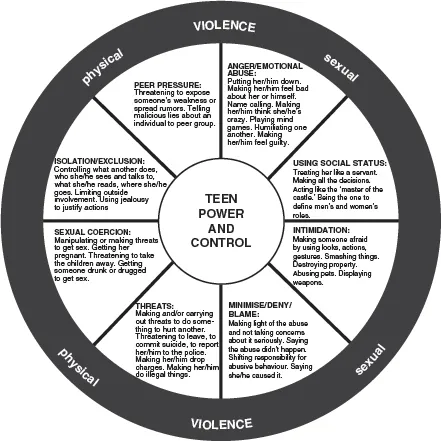

An influential definition of adult domestic abuse, developed by Pence and Paymar (1993), was the Power and Control Wheel. The originating wheel was devised from interviewing female partners of domestically violent men about their experiences of violence and abuse. A recent addition, the Teen Power and Control Wheel (available from the DAIP website), reflects the types of control that adolescents might experience in dating relationships. This has been presented diagrammatically in Figure 1.1 (reproduced with permission from DAIP).

As can be seen, many of the behaviours identified are related to physical, psychological and sexual violence/abuse (an overview of these behaviours follows). This is useful for understanding the extent of different behaviours that could be identified as abusive in adolescent relationships. What is unclear, however, is how the behaviours were identified – whether this was based only on a sample of females, when evidence indicates that males may be just as likely as females to experience them. Consequently, whilst it provides a useful educational tool, its validity is unclear.

Official definitions

On a general level, legal definitions of violence have existed for over 100 years in the UK, having been outlined first in the Offences against the Person Act 1861. A statutory definition of ‘domestic’ was developed in the mid-1970s (Dobash & Dobash, 1979) with the passing of the civil justice Domestic Violence and Matrimonial Proceedings Act 1976, in which ‘domestic’ referred to either spouse or heterosexual cohabitants (Burton, 2008). Legal definitions have subsequently been broadened, to include the diverse array of ‘domestic’ arrangements that exist such as current or former spouses, civil partners, and cohabitants (heterosexual and same-sex), those in a civil partnership, those who are parents or have parental responsibility for a child or those who were or are currently in a long-term relationship (Reece, 2006). What remains unclear is how this would relate to adolescents in a dating relationship. There is no legal definition of ‘dating relationship’ outside of cohabitation. It is likely, therefore, that young people engaging in violent acts towards an intimate would be held to account to the relevant criminal sanctions, given that the age of legal responsibility in most developed countries predates early adolescence with an international median of 12 years, ranging from 6 to 18 (Penal Reform International, 2013). However, currently there is no statutory offence for ‘domestic violence’ in the UK (Bowen, 2011a), and this fact is mirrored within ADV. Therefore, no legal definition exists for either.

Internationally across Europe, and nationally in England and Wales, the relevance of violence in relationships to young people has been formally acknowledged, although not clearly adopted within statute as yet. The Istanbul Convention (Council of Europe, 2011) defines domestic violence as:

all acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence that occur within the family or domestic unit or between former or current spouses or partners, whether or not the perpetrator shares or has shared the same residence with the victim. (p. 8)

This definition acknowledges the potential for non-cohabiting or dating relationship contexts. In addition, it is formally acknowledged in the Convention that violence in relationships can include those aged ‘below 18 years’ and it does not specify a lower age limit for inclusion in the definition. The Convention seeks to unify at a European level a comprehensive and equitable response to domestic violence, support for victims, criminal justice response, intervention and prevention efforts.

The British cross-Government definition of domestic abuse was updated with effect from 31 March 2013 to explicitly include 16- and 17-year-olds and coercive control. It is interesting that the government decided to impose a lower age limit, in contrast to the Convention, and contrary to the clear empirical evidence attesting to this issue in younger adolescent relationships. The new definition has also been adopted by the Crown Prosecution Service, the Home Office, and the Association of Chief Police Office and defines domestic abuse as:

any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive, threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are, or have been, intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality. The abuse can encompass, but is not limited to: psychological; physical; sexual; financial; emotional.

Further specific definitions of controlling behaviour and coercion are also provided. This definition is useful in capturing the breadth of different relationships that partner violence can happen in, and acknowledging all the different types of violence that can be classified as abuse.

What is adolescent dating violence?

The National Centre for Victims of Crime (2012) identifies ADV as including: controlling behaviours (for example, not letting you go out with friends, telling you what to wear), verbal and emotional abuse (name calling, jealousy), physical abuse (shoving, hair pulling, strangling) and sexual abuse (unwanted touching or kissing). Such behaviours are often used in combination. There are numerous examples of different types of behaviours associated with the different categories of ADV, but the list is extensive. Within the literature broadly speaking, there are three subtypes commonly studied and generally identified as being a feature of ADV; these subtypes are physical abuse, psychological/emotional or verbal abuse, and sexual violence/abuse (Wekerle & Wolfe, 1999).

Physical abuse

Physical abuse covers a wide range of behaviours. Foshee and colleagues (Foshee, Linder, MacDougall, & Bangdiwala, 2001; Foshee et al., 2008; Foshee et al., 2014) have studied this extensively and list several examples of physical dating violence that include: scratching, slapping, pushing, slamming or holding someone against a wall, biting, choking, burning, beating someone up, and assault with a weapon. Bonomi et al. (2012) identify similar types of behaviours suggesting physical dating violence includes slapping, hitting, scratching, pushing, kicking, and punching. Likewise, physical violence has been referred to as any actions that cause pain and injury with reference to different behaviours such as spanking, shoving, punching with hands, feet and objects, throwing objects at partner, hair pulling and biting (Halpern, Oslak, Young, Martin, & Kupper, 2001; Sesar, Pavela, Simic, Barisic & Banai, 2012).

Figure 1.1 Teen Power and Control Wheel

Psychological/emotional or verbal abuse

Like physical abuse, psychological/emotional or verbal abuse encapsulates a broad array of beha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Contextualising Violence and Abuse in Adolescent Romantic Relationships

- 2 The Impact of Adolescent Dating Violence

- 3 Risk and Protective Factors for Adolescent Dating Violence

- 4 Issues in Adolescent Dating Violence Risk Assessment

- 5 What Works When Intervening in Adolescent Relationship Violence?

- 6 A Framework for Intervention Development

- 7 A Framework for Evaluating Interventions for Adolescent Dating Violence

- 8 Drawing It All Together: A Research and Practice Agenda

- References

- Index