eBook - ePub

Managing Towards Supply Chain Maturity

Business Process Outsourcing and Offshoring

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Towards Supply Chain Maturity

Business Process Outsourcing and Offshoring

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This text takes a view of the crucial issues involved in supply chain management. The discussion introduces the concept of risk, information and social capital management that will ensure supply chain excellence and maturity according to the Poirier's model.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Managing Towards Supply Chain Maturity by M. Szymczak, M. Szymczak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Supply Chain Management

Maciej Szymczak, Mariusz Szuster, Grażyna Wieteska and Anna Baraniecka

1.1 The essence, structure and objectives of the supply chain (Maciej Szymczak)

In the face of the growing rate of globalisation processes, stronger competition and increased flexibility of business lines, companies have ceased to focus exclusively on what is happening within their own organisation. They have abandoned an egocentric approach, which was based on purely market-related, transactional relationships with their environment. One may conclude that thinking in categories of a network of dependence and relationships has unquestionably become one of modern management’s key paradigms – justified in the context of the global economy. As K. Obłój states (2002, p. 64), the time of the ‘lone gunslinger’ is drawing to an end, the future is not in aligning with single companies as much as with networks of companies that collectively influence the standards of market operations. Therefore, the supply chain should be understood as a network1 of entities delivering the product (or service) to the market, end-customer or consumer. A variety of entities are involved in delivering the product to the market; they, either individually or in cooperation, carry out diverse processes; many flows are recorded within the supply chain structure itself. A detailed description of the supply chain requires application of the following approaches (Witkowski 2010, p. 13):

–subjective,

–objective,

–process-based.

The subjective structure of the supply chain covers companies which obtain certain resources from nature, companies which process resources, trading companies, service providers and waste treatment and storage plants. These last facilities do not actually ‘deliver a product to the market’, a process usually referred to as ‘from field to table’, but recover used or damaged goods or reusable packaging from the market, referred to as ‘from dust to dust’. Due to the ecological and social importance of waste treatment, storage and reuse processes, these links in the supply chain cannot be ignored. The end-customer is also frequently included in the subjective structure of the supply chain. In other words, it is end-customers who trigger the flow of resources and the entire mechanism of the supply chain by making market choices, satisfying needs and having specific financial means at their disposal. The purpose of the supply chain is to achieve customer satisfaction (adding value), which translates into the purchasing and profits of companies operating within the supply chain (Bovet and Martha 2000, pp. 2–5). Nowadays, the end-customer often has a much larger influence on what he or she is offered and provided with by the supply chain.

In the light of the above, the essential object of supply chain management is product flow2. However, the term ‘product’ is rather more appropriately used in the context of a finished product to be marketed, i.e. in reference to the final stage of the supply chain, which focuses on distribution. At earlier stages, we deal with modules, semi-finished products, subcomponents, parts, production materials and work-in-progress (unfinished products). Therefore, we can generalise and say that material flows are the basic object of supply chain management. These are not, however, the only flows in the supply chain. Flow management requires information that helps plan, organise and control the flow of resources, so as to provide the end-customer with the finished product in the desired place, at the right time, in the right quantity, in proper condition at a pace that avoids downtimes, bottlenecks and excessive inventory in individual links of the supply chain. Information must be fed along the supply chain, between individual links and, occasionally, some links must be skipped, e.g. between the manufacturer and the retailer. Therefore, information flow should be included in the supply chain. Moreover, financial flows occur in the supply chain as a result of purchase and sales transactions concluded between supply chain links. These also reflect the value-adding processes that occur in consecutive links. We may conclude that these flows basically occur in another chain made up of financial institutions providing services to the supply chain links, such as banks and factoring and insurance companies, which should be marginalised3. Hence, three major flows may be distinguished in the supply chain: material, information and financial flows.

Putting a product onto the market involves many actions: research and development (a concept must be created, a product developed and designed), market and potential customer research (the manufacturing of the product and commercialisation of the idea must be justified), purchase (any necessary resources must be purchased), manufacturing (the product must be made), marketing (the potential customers must be informed about the new product), logistics (the product must be delivered and made available) and sales. Moreover, the processes of waste collection, segregation, treatment and management should be taken into account. In addition, all these processes require funding actions. The literature on the topic specifies various types of supply chain process, and the different processes have been distinguished. An analysis of the approaches helps pinpoint eight basic supply chain processes (Cooper, Lambert and Pagh 1997; Croxton et al. 2001):

–customer relationship management,

–customer service level management,

–demand management,4

–order fulfilment,

–manufacturing flow management,

–procurement management,

–product development and commercialisation

–returns management.

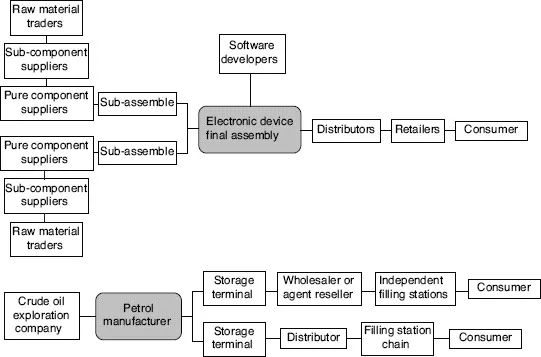

From the perspective of these three complementary approaches, a supply chain may be defined as mining, manufacturing, trading, service providing companies and their customers, between which products, information and funds flow (Witkowski 2010, p. 19). The supply chain means the integration of key business processes carried out by all consecutive suppliers of products and providers of services and information that add value for customers and stakeholders5 (Lambert, Cooper and Pagh 1998, p. 1). The supply chain may be understood as an extended enterprise in which the importance of the boundaries to-date of companies carrying out its processes is decreasing. The flow of products, information and funds in an extended enterprise is strictly coordinated (Langley et al. 2009, p. 20). Examples of supply chains are presented in Figure 1.1. Today we often speak about the demand for flexible (Gow, Oliver and Gow 2002), agile (Christopher 2000), proactive (Smeltzer and Siferd 1998), responsive (Gunasekaran, Lai and Cheng 2008) and resilient (Christopher and Peck 2004) supply chains; in other words, without going into an explanation of the differences between them, supply chains that can dynamically adapt to changes in their environments and to market trends. Supply chain flexibility is required in five dimensions (Vickery, Calantone and Droge 1999):

Figure 1.1 Examples of supply chains

Source: Own study.

–product flexibility (customisation),

–volume flexibility,

–launch flexibility,

–access flexibility,

–responsiveness to target markets.

The success of the supply chain depends on the integration of the management systems used by its links, collaboration in the supply chain, the establishment of long-term relationships, the coordination of flows, the compatibility of information systems, and mutual commitment, responsibility and trust (Moberg, Speh and Freese 2003).

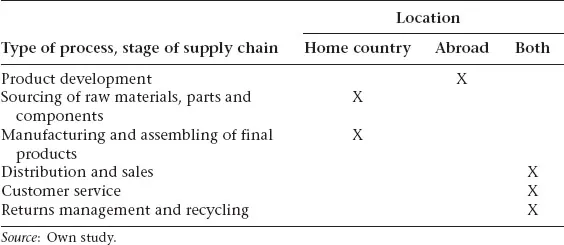

Procurement, manufacturing and distribution in a supply chain may be carried out in various countries. Some of these processes may be carried out in the home country, others abroad. This applies also to measures related to waste recycling – Table 1.1. These processes are handled by units of the company or by third parties located in the respective countries. A company either places its own operation abroad or looks for a contractor (international sourcing). This does not apply to processes that do not require a commercial presence in the specific country. The scope of international collaboration among companies and its intensity depend most of all on the form of internationalisation (export, licence transfer, franchise, foreign branch, manufacturing plant abroad) and on the scale of business (number of export, licence or franchise contracts, number of branches and manufacturing plants). The scope of international collaboration in a supply chain depends also on the functional strategies of the company, the sector it operates in and many other factors that make a varied impact on the company’s presence in foreign markets.

Table 1.1 Establishment of an international supply chain

The measures undertaken by companies to deliver products to market in the complex international environment of a supply chain require not only the efficient execution of the temporal and spatial transformation of goods, but also the decomposition of value chains, the isolation of specific measures, and the transfer of their execution to own units abroad or foreign partners, so as to make the best use of resources, competences, experience and economies of scale. Supply chain development leads to new forms of collaboration. One of these forms is co-manufacturing (contract manufacturing, co-makership), which consists in assigning some operations, which have to date been an integral part of the manufacturing process, to suppliers or purchasers. It usually pertains to certain pre-manufacturing activities related to the preparation of production, or post-manufacturing activities in order to configure the product to the specific market. Another form of collaboration that is becoming increasingly popular is to involve a third party in the preparation of products for distribution and sales (co-packing, contract packing). This usually comes down to repacking products from bulk into unit packages (or vice versa); preparing merchandising, promotional and seasonal sets; adding product samples; packing in blister packs; or labelling. Very often, logistics service providers are involved in co-manufacturing and co-packing.

These forms of international collaboration in supply chains increase the distance between the product and manufacturer and between the manufacturer and the point of manufacture. This results in the emergence of own labels, regional labels (e.g. ‘made in the EU’) or no-name products. The development of this type of collaboration and the growing specialisation of individual supply chain links cause a division of tasks based on the objective approach, apart from the division of tasks between the supplier, manufacturer, distributor, exporter, haulier, seller, etc. In this case, each entity performs the tasks by contracting complementary services from partners. Multilateral collaboration results in the operation of supply chains increasingly often extending beyond the vertical structure. Horizontal relationships, which are often extended, are being established at all levels. Supply chains evolve into supply networks. The dynamic of these processes has attracted the attention of many analysts and scientists to supply networks; there are also many studies researching supply networks (Nassimbeni 2004). The hierarchical coordination of operations in supply chains is being replaced by network coordination. These transformations are best shown by M. Govil and J-M. Proth (2002, p. 7), who defined a supply chain as a global network of organisations that cooperate to improve the flows of material and information between consecutive entities in order to provide customer satisfaction.

One should realise, however, that aside from the collaboration required by the increasing demand for recourse to third parties, especially unique ones, processes of competition also occur. Entities performing the same functions compete with one another in raising the quality of service and reducing cycles or costs. The intertwining collaboration and competition processes, at the level of both individual links and groups, induce brand new systems in the classical strategic triangle: corporation – customer – competitor (Ohmae 1982, pp. 91–98). Compared with classical supply chains, this enriches the inter-organisational relationships that occur in these systems. A. Sulejewicz (1997, p. 68) suggests that they be considered under the control – cooperation – competition paradigm (3C paradigm) that allows him to pinpoint three types of collaborative relationships typical of entities in a network:

–pure cooperation,

–co-optrol,

–co-opetition.

Pure cooperation is based on a collective strategy with a negotiated agreement. Co-optrol occurs in integrated asymmetrical systems, which are dominated by one or more partners over the others. It occurs in the case of co-making and co-packing and anywhere an integrator operates, determining the strategy and profile of operation, distributing tasks and supervising the division of benefits. The role of the integrator does not have to be concentrated within one entity (hierarchical networks); there may be a number of integrators (polycentric networks). Co-opetition means a situation in which two market competitors start cooperating. The relationship that is established between the entities has the elements of both cooperation and competition. This makes it possible to discuss the relationship in terms of a strategic alliance. In supply networks, co-opetition most often occurs in the area of manufacturing and distribution. The cooperation of competitive manufacturers is aimed at the development of new, innovative products and then, after star...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Supply Chain Management

- 2 Supply Chain Development Process

- 3 Supply Chain Risk

- 4 Outsourcing and Offshoring as Factors Increasing Risk in Supply Chains

- 5 Supply Chain Risk Management

- 6 Information Management in the Supply Chain

- 7 Social Capital Management in the Supply Chain

- Summary

- Index