This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Double Crisis of the Welfare State and What We Can Do About It

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book analyses the immediate challenges from headlong cuts, root-and-branch restructuring and the longer-term pressures from population ageing. It demonstrates that a more humane and generous welfare state that will build social inclusiveness is possible and shows how it can be achieved.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Double Crisis of the Welfare State and What We Can Do About It by P. Taylor-Gooby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Social Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Double Crisis of the Welfare State

Abstract: The British welfare state faces a double crisis: immediate cutbacks in response to the recession bearing most heavily on benefits and services for those on low incomes, especially women and families, and longer-term pressures on health and social care, education and pensions from population ageing and other factors. Government decisions to focus the cuts on the most vulnerable exacerbate the first crisis. Policies which fragment and privatise the main state services in response to the second undermine the tradition of a universal welfare state. The cuts are deeper and more precipitate than any among comparable developed economies or for at least a century in the UK.

Keywords: cuts; double crisis; fragmentation; liberalism; population ageing; privatisation; retrenchment; welfare state; women

Taylor-Gooby, Peter. The Double Crisis of the Welfare State and What We Can Do About It. Basingstoke: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2013. DOI: 10.1057/9781137328113

Macmillan, 2013. DOI: 10.1057/9781137328113

The welfare state, the idea that a successful, competitive, capitalist market economy can be combined with effective services to reduce poverty and meet the needs people experience in their everyday lives, was the great gift of Europe to the world. Now it is under attack and it is a war on two fronts. The conflict is experienced with especial severity in the UK. The response to the 2007–8 banking crisis, repeated recessions and economic stagnation in this country has been to balance budgets by cutting government spending rather than increasing taxes. The harshest cuts are in social provision, with the poorest groups bearing the brunt.

Standing behind the immediate attack on the welfare state is a second crisis, which now attracts rather less attention in policy debate. Projections of the numbers likely to use the main welfare state services (health and social care, education and pensions), of future wage levels and of other factors indicate that the costs of maintaining, let alone improving, provision will rise steadily during the next half-century. Tax-payers will have to pay more or accept lower standards.

This book addresses the double crisis of the welfare state with a particular focus on the UK. It shows how the immediate and longer-run pressures interact. The second, slow-burn crisis sets the mass of the population against more vulnerable minorities. The high-spending expensive services, such as health, education and pensions, are top priorities for most people. Spending on the less popular benefits and services that redistribute to the poor is steadily eroded. The government’s response to the immediate economic crisis builds on this division, cutting the redistributive benefits to maintain the big-spending mass services. The fact that this is happening in a context of growing inequalities and social divisions makes the task of developing a humane and generous, effective and politically feasible response to the double crisis that much harder.

In this chapter we examine the twin crises in more detail. Chapter 2 considers how they interact and analyses their impact on the politics of state welfare. Chapter 3 examines the problems faced in making a case to sustain and improve provision in the current context, focusing on redistributive welfare for the poor. Chapter 4 extends the discussion of feasible, effective and humane policies to health and social care, pensions and education. Chapter 5 brings these arguments together, evaluates the opportunities for more generous and inclusive directions in policy and identifies the political forces that might be harnessed to drive them forward.

The immediate crisis: recession, cuts and restructuring

Britain’s welfare state is unusual in a European context in being financed mainly through taxation rather than social insurance payments from employers, workers and government. Tax finance presents the question of who pays in and who gets the benefits more directly and raises immediate issues of stigma and desert. The system includes high-quality and relatively cheap mass health care, pensions at modest levels, an average education system that achieves good results for those at the top but not for others, relatively extensive (but costly) social housing, and weak provision for those on low incomes, with limited skills or who are vulnerable for other reasons. The main division lies between the universal services that meet the shared needs of the mass of the population (health care, education and old age pensions) and those directed at poor minorities (unemployed, sick and disabled people, lone parents, those who can’t afford rents and families in low-waged work). It is here that questions of desert arise and that entitlement tends to be policed through means-testing and stringent work tests.

Britain’s response to the economic crisis is also unusual.

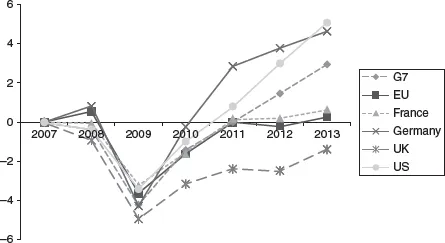

The 2008–9 recession was the deepest since at least the great crash in the 1929–31 and has already lasted longer than any previous recession for at least a century. Figure 1.1 shows the pattern of economic growth across the two major comparable European economies, France and Germany, the EU as a whole, the US and the G7 group since the start of the first recession in 2007. G7 includes the largest established capitalist economies: the US, Canada and Japan as well as the UK and France, Germany and Italy and offers a global comparison. The graph plots the decline in GDP and shows how long it took to return to the pre-recession level. The collapse in 2009 was of between 3.5 and 5 per cent of GDP. All of the countries and groups of countries had recovered to their 2007 level of output or surpassed it by 2011, apart from the UK. Germany, the US and the G7 then continue to grow, while France and the EU as a whole stay at about 2007 levels. At the time of writing, some 60 months after the onset of recession, the UK is still struggling to return to its previous position. It is not expected to do so for at least another year.

Figure 1.1 GDP change as percentage of 2007 GDP, 2007–13

Source: Author’s calculations from IMF (2012), projected from 2012.

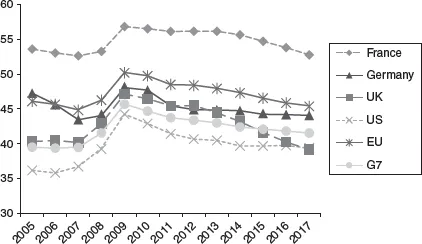

The UK has, effectively, lost the resources that would have been produced over the period since 2007 if output had simply stood still. One outcome has been a real fall in living standards for most people as wages fail to keep pace with price rises, about 7 per cent between 2009 and 2013 for those on median incomes (Joyce 2012, 15). So far as the welfare state goes, the response of the incoming coalition government in 2010 was to cut state spending radically, although as Figure 1.2 shows, spending in the UK was already at the average of the G7 and much lower than in the other major European countries or the EU average in the better times of the early 2000s. The graph shows how spending has already fallen sharply. On current plans it will continue to decline even when the economy recovers. This pattern differs from those elsewhere. Most countries tend to stabilise state spending close to or slightly above pre-recession levels when resources return. In the UK, spending will sink further below European spending levels to fall beneath those in the G7 by 2014–15 and in the US by about 2016–17. This marks a decisive shift in the level of government involvement in society and in the economy. The UK has not spent a smaller proportion of national resources on public services than the traditionally market-centred US during the period of more than a century for which good records are conveniently available.

Figure 1.2 State spending, major economies, 2005–17 (per cent GDP)

Source: IMF (2012), projected from 2012.

The cutbacks are combined with an equally profound programme of structural change. We consider the two aspects of reform, cuts and restructuring, separately.

The cuts

The 2010 government set itself the objective of eliminating the budget deficit by 2014–5, revised to 2017–18 in 2012 as economic growth failed to return (HM Treasury 2010, 2012b). The programme set out in the 2010 Spending Review envisaged massive and rapid cuts in public spending, about £100bn in all, including about one-fifth of the £166bn budgeted for housing and community, environmental protection, law and order, defence, economic affairs and other public services in 2010, and about 18 per cent of the £105bn budgeted for welfare for the poor, housing benefit, unemployment and family benefits and for disabled people (HM Treasury 2010). The target for benefit cuts was raised to 22 per cent in 2012. By contrast, the government chose to protect the mass welfare state services (health, education and pensions) which account for about 60 per cent of state spending. These experienced relatively minor cutbacks in current spending, although capital spending plunged headlong, by three-fifths for education and one-fifth for health services (IFS 2011, 138, Chowdry and Sibieta 2011, 4). The decision to ring-fence current spending on the more popular services resulted in much greater damage to benefits for low-income people and to less popular areas of state provision.

The cuts accounted for some three-fifths of the resources required to balance the budget and tax rises (mainly a legacy from the 2005–10 government) some two-fifths. They included a rise to 50 per cent in the top rate paid by the 2 to 3 per cent of tax-payers with incomes over £150,000 (cut to 45 per cent in 2013), a rise in National Insurance contributions for all employees of 1 per cent, and an increase in the mildly regressive VAT, plus a one-off banking levy, a rise in Capital Gains Tax (later reversed) and increases in alcohol and fuel duty.

The cutbacks coupled with immediate stimuli intended to promote a return to growth, such as the 2009–10 car scrappage subsidy, cuts in corporation tax and other taxes on business, further tightening of public spending, and £375bn of ‘quantitative easing’ (whereby the Treasury encourages private sector lending by increasing the availability of money to banks), failed to prevent a further slide into recession in 2011–12. By 2012, Office for Budgetary Responsibility projections indicated that the budget deficit would not be eliminated until after 2017–18 and that there is little hope of extra buoyancy to compensate for the lost production of the years of recession (OBR 2012a, table 1.2). The government remains committed to further cutbacks focused again on short-term benefits and local government, in an attempt to stimulate private sector led recovery.

This programme failed to achieve its goals of reducing the deficit and stimulating growth. Further cutbacks in benefits were introduced in 2013, with £5bn diverted from public services to investment in infrastructure and a cut in corporation tax to 21 per cent, the lowest rate since the tax was introduced in 1965 (HM Treasury 2012b).

Cutbacks on this scale are exceptional in British policy-making and have been much discussed (for example, Crouch 2011, Gamble 2011, Gough 2011a, Skidelsky 2012). Here we outline the government’s underlying assumptions, examine how the cutbacks are structured to achieve a specific impact and consider the risks run in pursuing these policies.

Assumptions underlying the cuts: In recent years most governments in developed economies have pursued economic policies that balance two underlying approaches. Those inspired by Keynesian counter-cyclical theory see the problems of economic downturn in terms of the resources (factories, people, investment capital) that lie idle. They argue that government must make up for the contraction in private investment. This can be financed by borrowing, which temporarily increases indebtedness but can be paid off out of the proceeds of future growth. An alternative liberal approach argues that the long-term solution must rely on competitiveness in international markets and hence on low public deficits and free markets providing good investment opportunities to attract private capital. The latter view is more appealing to those who believe that there are structural weaknesses (as they see many of the restrictions on market freedoms) in national economies that currently damage competitiveness and that may now be corrected.

Both viewpoints have influenced policy in developed countries, but the balance has shifted more in the liberal direction as stagnation has continued (Skidelsky 2012, Crouch 2011, Davies 2010). Figure 1.2 shows that the response to the second recession of 2011–12 (the slight upswing in state spending in those years) was much weaker than that to the first recession in 2008–9. The UK is the leading exponent of liberal economic remedies, cutting spending harder and faster than any of the major developed economies, indeed than any European economy apart from those compelled to do so as a condition of IMF, ECB and EU loans.

Structure and impact of the cuts: The UK cuts are indeed exceptional. Roughly two-thirds of government spending is directed at welfare state provision, in order of scale: the NHS, pensions, education, other cash benefits including housing benefit and benefits for disabled people, social care and social housing. The remainder is spent on the military, police and prisons, the rest of local government (apart from education, social housing and social care), transport and environmental policies, again in order of spending. This complex interactive mechanism disposes of about a third of GDP, of everything that all economic activity in the country generates in a year. The cuts affect all areas but are not spread evenly. Non-welfare services lose roughly a fifth (IFS 2011, figure 6.3). When it comes to the welfare state, the cuts are targeted away from the most expensive and popular areas which are used by large numbers of voters, such as the NHS, education and pensions. Instead they are concentrated on the rather lower spending but less popular benefits and services for lower-income people of working age: benefits for low-paid, unemployed and disabled people, for families and children, and for housing.

The cuts will save about 27 per cent of planned spending on disabled people of working age (some £16.4bn) through reforms to employment support allowance, the replacement of disability living allowance by the less generous personal independence payments and more stringent work tests (DWP 2012a, 2012b). They will freeze child benefit until 2013 and remove it from the better-off, cut working families tax credit, reduce the social housing budget by three-quarters (IFS 2011, table 6.2) and introduce harsher entitlement rules and a series of cuts to housing benefit that will limit entitlement for single and for younger people, make it difficult to claim outside low-income areas and for many kinds of housing and reduce benefit levels sharply. These cuts impact with particular severity on women, who are the main recipients of child benefit, tax credit and housing benefit, and make up some 90 per cent of single parents, and children.

Changes to the benefit uprating rules will result in further reductions in spending on benefits for people of working age that will continue to drive down costs indefinitely. Uprating for pensions will be set at the highest of the retail price index, rises in earnings or 2.5 per cent, ensuring that this group shares the improvements in living standards of the mass of the population. Rises in benefits for those of working age (child benefit, housing benefit, job seeker’s allowance, income support and tax credits) will be limited to 1 per cent between 2013–14 and 2015–16 and then linked to the Consumer Price Index. This index does not include mortgage interest and calculates below the arithmetic average of prices for the items included on the assumption that purchasers will continually substitute cheaper for more expensive ones. The projected outcome is to reduce the rate at which benefits rise every year by between 1 and 2 per cent indefinitely. Lower-income families of working age will experience harsh immediate cuts in living standards and a continuing downward pressure, which will exacerbate the division between better- and worse-off groups. About two-thirds of the money saved will come from benefits paid to women (WBG 2012b, 3).

The division between welfare for working age poor and for pensioners will be embodied in a re-configuration of the benefit system. All benefits except child benefit and those for pensioners will be combined into a new Universal Credit from 2013. The new system will have the advantages of simplicity and transparency and will mitigate slightly the ‘poverty trap’, whereby people moving off benefit into paid work may experience only a small increase in net income because they risk losing benefits nearly pound for pound against any extra money they earn. Of the 7.1 million people likely to be claiming the benefit, some 2.9 million working-age families will experience a short-term net gain, against some 1.8 million, mainly single people, who will lose out (IFS 2012c). However the cuts in uprating and other restrictions described above will continue to drive down living standards for the poor. The pressures on benefits will be intensified by further cuts in the 2013 budget of about ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 The Double Crisis of the Welfare State

- 2 Why Add Restructuring to Cutbacks? Explaining the New Policy Direction

- 3 Addressing the Double Crisis: The Welfare State Trilemma

- 4 Responding to the Trilemma: Affordable Policies to Make Popular Mass Services More Inclusive

- 5 Making Generous and Inclusive Policies Politically Feasible

- Bibliography

- Index