eBook - ePub

The Politics of Extreme Austerity

Greece in the Eurozone Crisis

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Politics of Extreme Austerity

Greece in the Eurozone Crisis

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume investigates the policies and politics of extreme austerity, setting the crisis in Greece in its global context. Featuring multidisciplinary contributions and an exclusive interview with former Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou, this is the first comprehensive account of the economic crisis at the heart of Europe.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Politics of Extreme Austerity by G. Karyotis, R. Gerodimos, G. Karyotis,R. Gerodimos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Framing Contests and Crisis Management

1

The Contradictions and Battlegrounds of Crisis Management

Andrew Hindmoor and Allan McConnell

All societies face periodic and extreme challenges. In the past decade and more, many episodes have become ingrained in collective memories, such as the global financial crisis, sovereign debt crises, volcanic ash clouds, SARS, Japanese tsunami and nuclear meltdown, as well as terrorist attacks ranging from 9/11 to the mass shooting on the Norwegian island of Utøya and the bombing of the Boston Marathon. A common-sense view of the world might assume that when terrible events happen, all corners of society pull together to help cope with, manage and rebuild in the aftermath. Yet the realpolitik of crises is far removed from such ideals. This is not to suggest that good and noble intentions are absent during crises episodes. Indeed, periods of turbulence typically produce passions, heroism, moral and ethical courage, but they also produce fears, anxieties and often anger. The way in which leaders, parties, groups, media and citizens respond is typically a product of good intentions, interspersed with blame games, battles, recriminations and above all fundamental disagreement – occasionally violent – over what should be done to address the crisis.

This chapter does not seek to address the economic turbulence and the politics of austerity in Greece per se, although it does provide occasional linkage on a few key issues. What in essence it aims to do is map out and discuss a series of generic issues pertaining to the politics of crisis management. Doing so provides a broader context for others to draw on (in this volume’s chapters and elsewhere), allowing us to see the ‘Greek tragedy’ as not purely a unique episode never to be repeated in precisely the same way, but also as a period epitomising classic symptoms of the way in which societies contend with terrible events. The chapter is structured as follows. First, it unpacks the complex and contested nature of what constitutes a ‘crisis’. Second, it sets out an original framework, which allows us to examine the challenges for governing and opposition parties in times of crisis (fundamentally to work together, or maintain degrees of adversarial behaviour). This framework also provides us with a window into the broader battlegrounds and contradictions of managing crisis episodes. Third, it refines this framework and produces multiple fine-grained frames through which different governing and opposition parties may dispute all key aspects of a crisis, from its causes to what measures should be put in place. Fourth and finally, it builds on the foregoing analysis to identify broader battlegrounds and contradictions of managing crisis episodes. These focus on tensions in relation to whether societies should ‘get behind’ government in difficult times, political priorities influencing policy decisions, the influence of global pressures on national crisis decision-making, the extent to which the ‘old order’ should be protected, and the magnitude of reforms needed. Such issues perhaps exemplify the near ‘mission impossible’ (Boin and ‘t Hart, 2003) challenges of crisis management and crisis politics, as well as helping contextualise the Greek case and avoid the pitfalls of exceptionalism.

Unpacking the nature of crisis

When events happen such as 9/11 or a rogue individual embarks on a school shooting, a natural instinct is to move beyond the language of ‘normality’ to find words – such as ‘crises’ or ‘disaster’ – to help articulate the serious and exceptional circumstances which prevail. Yet the word crisis is by no means confined to such extreme events. The word crisis is everywhere in new and old media, from a label used to refer to the declining fortunes of celebrity marriages and football teams, to economic meltdowns and political regimes on the verge of collapse. There tends to be a view, especially when it appears as headline news, to assume that what constitutes a crisis is self-evident (see, e.g., Cottle 2009). But the pervasive feature of ‘crisis’ helps provide a clue that what one individual or group perceives as a crisis, another may not. As will become apparent, such contestation is one of the key themes in the Greek crisis (see especially Chapters 2, 3, 7 and 9, this volume).

Differing perceptions may be heartfelt and/or expedient. The term ‘crisis’ may be used for a host of different reasons, such as to attack political opponents, sell newspapers, seek attention for political causes, and inflate the series of events to push through policy reforms (Drennan and McConnell, 2007). One might be tempted, therefore, to see the term crisis as nothing more than a matter of perception, yet to do so creates the danger of forgetting that abnormal and threatening events can happen, which pose real challenges for public/private/non-governmental institutions and citizens, who are thrust outside their normal rhythms and assumptions of security, stability and their role/status/place in society.

A view of the world which assumes that crisis is a matter of objectivity and a matter of perception, are perfectly compatible, in the same way we might recognise that some individuals have greater income and wealth than others; still, there can exist vastly divergent views on whether such state of affairs are desirable. Crisis management literature often attempts to distil crisis conditions to ‘hard criteria’ such as severe threat, high uncertainty and limited time for decision-making (Rosenthal et al., 2001), but it also recognises that it can ‘shatter’ our understanding of the world (‘t Hart, 1993) (producing) complex, contested and contradictory views (Bovens and ‘t Hart, 1996; Brändström and Kuipers, 2003). We would argue that only by recognising such a nuanced assumption of crisis can we properly recognise that crises bring ‘real’, harsh challenges and widely differing views on what went wrong and what should be done.

The challenges for governing and opposition parties in times of crisis

Crisis pressures and party positioning

Crises typically pose two interrelated sets of challenges for crisis managers and policy makers (and by default, political parties) (Boin, 2004; Drennan and McConnell, 2007). The first is operationally related, in terms of identifying the appropriate policy tools and decisions needed to control and eventually eradicate the threat. These might include exclusion zones, curfews, bio security measures, troop deployment, emergency financial measures and even the activation of emergency state powers. The second challenge is a political symbolic one (see ‘t Hart, 1993). Governing and opposition parties need to make sense of rapidly evolving events under conditions of high uncertainty and often ambiguous and conflicting information/signals, and attempt to dominate political discourse with an authoritative ‘account’ of the crisis (typically in the face of media scrutiny, criticism and multiple demands from victims and families). If those in positions of power and authority are not able to convince citizens, media, stakeholders and others through public communication strategies that they are in control, they become vulnerable to impressions of crisis mismanagement, including neglect, delay, misjudgement and insensitivity.

If crisis management presents major challenges for crisis policy makers to respond appropriately, understanding the role played by political parties adds an additional degree of difficulty, even in the most elementary capturing of their positions. The closest to an exploration of this issue is Chowanietz (2010) in his study of political party reactions to 181 terrorist attacks in Germany, France, Spain, UK and the US, which identifies and measures opposition ‘criticism’ of government by leading party figures or spokespersons. Yet, identifying only instances of opposition critique fails to capture commitments or at least publicly articulated appeals for consensus. Also, not only do areas of consensus need to be factored in if we are to capture government-opposition relations, but consensus and conflict are not crude binary issues. In a speech to his party’s conference on 30 September 2008 at a time when the repercussions of the sub-prime crisis and the collapse of key US financial institutions was being felt keenly across the Atlantic, the (then) UK Conservative Opposition leader David Cameron (2008) stated:

We should always be ready ... . to put aside party differences to help bring stability and help bring reassurance ... . But this should never be a blank cheque. We should not, we will not suspend our critical faculties.

We need, therefore, an aggregate sense of where parties stand in relation to each other, with particular reference to degrees of consensus and conflict, rather than either/or. Here we use four simple categories as an initial heuristic reference point (in the latter part of this chapter we will populate them with fine-grained detail). We have labelled them in such a way as to symbolise the broader extent to which governing and opposition parties articulate common messages and/or conflicting ones.

The most consensual is Rally Around the Flag, where there is strong and unqualified cross-party agreement that it is in the national interest for party politics to be put aside in order to tackle the crisis. This was particularly evident in the US, France and Spain in the wake of the 9/11 attacks (Chowanietz, 2011). Such party positioning may be driven by genuine support for a consensual approach, but there may also be partisan benefits, simply by virtue of the fact that a party can portray itself as fit for office, precisely because it is prepared to put the interests of nation above the interests of party. Of course, such a strategy can bring with it the risk of one party failing to differentiate itself from its opponents.

One step removed from Rally Around the Flag is what we term Strained Consensus. Here, there is cross-party agreement in principle that a bipartisan approach is needed, but that criticism of the opposing party can be legitimate. An example which epitomises this is the UK Labour and Conservative attitudes to the war in Afghanistan for the period from 2001 onwards (see Honeyman, 2009). The Conservative opposition remained a staunch supporter of the Labour government’s commitment to British involvement in the invasion of Afghanistan, albeit with strain over issues such as levels of equipment, troop reductions, as well as the speed and ‘sofa’ style of decision-making which took the UK to war in the first place.

A further shift towards conflict but one step removed from Classic Adversary Politics is a set of relationships we describe as On the Brink of Inter-Party Warfare. Here, inter-party conflict is dominant, but small aspects of cross-party agreement remain, as has been the case over the period 2011–14 with the Labour opposition in the UK and its attack on the coalition government’s austerity measures in response to the economic fallout from the global financial crisis. Small areas of consensus remain, such as the need for cuts, with disagreements on issues, such as the extent and ‘fairness’ of cuts.

Furthest removed from Rally Around the Flag is Classic Adversary Politics where inter-party conflict is rife and there are no apparent areas of consensus in terms of the nature of the crisis and how it should be tackled. The US debt-ceiling crisis exemplifies. Over a period of some two months in mid-2011, an extraordinary level of bitter adversarial behaviour emerged across the often pragmatic Democrat-Republic divide, with no common ground of any significance, no concessions to political opponents, and a mutual willingness to risk default on debt rather than concede to the other’s deficit reduction proposals.

We do not suggest that party positions will always fit neatly into one of these four categories and indeed this issue will be examined later. In order to prepare the ground for doing so, we need to develop our understanding of party positioning during times of crisis.

Drivers for party positioning

Why do governing and opposition parties lean towards adversarial or consensual relations with each other in crisis situations? An entire industry has built up within political science, attempting to explain party behaviour in terms of spatial positioning in relation to voters, coalition formation, party ideals and much more. There is no single, universally agreed theory of party behaviour (despite some attempts, e.g., Strøm, 1990) and almost nothing with regard to party behaviour in times of crisis. In such contexts it is certainly not possible to offer a definitive explanation for party positioning in times of crisis, but it is possible – as a first step – to map out a range of possible explanations, depending on our assumptions of what drives party behaviour.

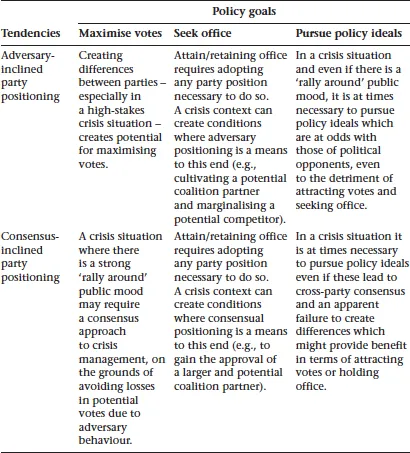

Table 1.1 identifies how three different models would conceive of a party’s behaviour (in relations to its opponents) in times of crisis. These models, based on differing driving forces of party behaviour, are neatly summarised by Müller and Strøm (1999) as vote maximisation, the quest to hold office, or the pursuit of policy ideals. Party strategies often involving juggling these competing priorities, and pursuing public positions and policies which reflect the complex relationship between them. These three models are necessarily simplified, not mutually exclusive and there have been many refinements over the years (e.g., on valence issues and the vagaries of electoral systems), but they do provide a framework to help explain how a party may be driven by a particular goal during a crisis episode but face very different strategic options in terms of how to achieve that goal.

Vote-maximisation is the classic Downsian perspective. One can see why adversary behaviour in a crisis might be considered a means to this end, because it differentiates parties for the purposes of maximising electoral appeal. When the UK was beset by a major foot-and-mouth crisis in the first few months of 2001, severe damage was being done to both the farming and tourist industries. Yet in the context of a looming general election a few months later, there were virtually no areas of agreement between the main Labour government and the Conservative opposition on how best to resolve the crisis. Nevertheless, crisis episodes, especially in the initial days, hours and even weeks, can produce a ‘rally around’ public mood, where there is intolerance of parties appearing to put partisanship above the national interest. In Norway after the mass shooting by Anders Breivik in 2011 which killed 69 people, mostly teenagers, all seven parties in Parliament coalesced on many issues, including a commitment to cancel forthcoming local elections. The vote-maximisation model would assume, however, that electoral calculation would still lie behind such consensual manoeuvres, on the grounds that overt partisanship would alienate voters and lead to a diminishing of electoral support.

Seeking office may be another goal of parties, as indicated particularly by the literature on coalition building and bargaining. There may be, depending on the context, a certain appeal for a political party in adopting an adversary-inclined position, because it can help cultivate conditions to marginalise potential competitors also seeking coalition. Again, however, there may also be an inclination towards adopting a more consensual approach with political opponents. A smaller party, in particular, may seek to ally itself with the crisis position of a major party, simply to seek (or maintain) its membership of a coalition government. Such issues are particularly relevant to Greece in the period post-November 2011. It has produced a series of coalition governments (Papademos: November 2011 to May 2012; Pikrammenos: May to June 2012; Samaras: since July 2012), which have proved to be the longest, and perhaps only meaningful, period of coalition government in a country characterised by a very adversarial and polarised political culture. The hitherto norm has been that collaborating with ‘the enemy’ equates to electoral suicide. Given the gravity of the crisis, therefore, not participating in the coalition government may have been perceived as potentially harmful to the electoral prospects for several parties. This shift also illustrates that vote-maximisation and coalition building are not mutually exclusive. As is arguably the case with Greece, in times of crisis the ‘least worst’ strategy for a party seeking electoral appeal, at least in the short-term, and avoiding electoral suicide may in fact be entering into a coalition.

The pursuit of policy ideals is another potential goal of parties. Parties may, regardless of contexts such as public moods or election timing, adhere to ideological principles in terms of their willingness (or not) to work with their political opponents to resolve a crisis. Depending on the specific beliefs, adherence to a particular stance may put a party in confrontation with its main political opponents. In Belgium during 2010–11, a stalemate between Dutch-speaking Flemish parties and French parties, reflecting deep-rooted social, cultural and political fault lines in Belgian society, led to a period of 541 days of political crisis without a government being formed. Yet the pursuit of party ideals can (often eventually) result in cross-party agreement, especially when doing so is articulated in terms of constructing a narrative of party tradition which places national interest above party interest.

Table 1.1 Models of party behaviour and explanations for party positioning in crisis situations

In sum: parties may be driven by different goals. Crisis episodes may muddy the waters of party strategy because adversarial or consensus-oriented approaches have propen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Dissecting the Greek Debt Crisis

- Part I Framing Contests and Crisis Management

- Part II The Policies of Extreme Austerity

- Part III The Politics of Extreme Austerity

- Part IV The Crisis Beyond Greece

- Appendix: A Timeline of the Greek and Eurozone Crises

- Bibliography

- Index