eBook - ePub

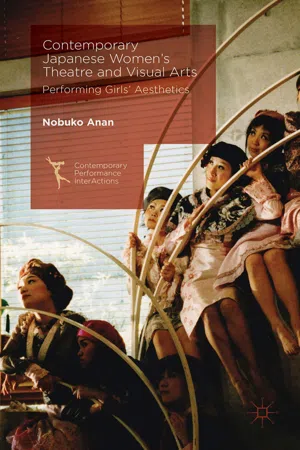

Contemporary Japanese Women's Theatre and Visual Arts

Performing Girls' Aesthetics

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book traces the history of 'girls' aesthetics, ' where adult Japanese women create art works about 'girls' that resist motherhood, from the modern to the contemporary period and their manifestation in Japanese women's theatrical and dance performance and visual arts including manga, film, and installation arts.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Contemporary Japanese Women's Theatre and Visual Arts by Nobuko Anan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Theatre History & Criticism1

Girls’ Time, Girls’ Space

MISHIMA: [I]t’s women who dominate time. It’s not men. Ten months1 during pregnancy is what women possess. …

TERAYAMA: But, women believe in another time according to which they bleed every twenty-eight days. This is why they are indifferent to the time created by SEIKO.2 Women are the watches themselves.

[……………]

MISHIMA: … [Women] exist within time. Men may end up existing outside of time, so they are so scared without watches.

TERAYAMA: So, I think that men need to stroll around searching for outside watches, because they are always accidental beings.

MISHIMA: That may be true. …

(Mishima and Terayama 2012: 36)

The July 1970 issue of the magazine Tide (Ushio) prints a conversation between novelist/playwright Mishima Yukio and theatre/film maker Terayama Shūji. Although titled “Can Eros Be the Basis of Resistance?” (Erosu wa teikō no kyoten to nari uru ka?),3 these two giants of the postwar Japanese arts world jump from one topic to another, from the New Left movement to eroticism, from gambling to Catholicism, from body-building to noh theatre. Towards the end of their conversation, Terayama, out of the blue, asks Mishima what he thinks of women. Terayama’s intention is not clear at all, but anyway, this opens up their brief discussion on women – or women, time, space, and body.

Terayama talks as if there were two different temporalities lived by women: ten months of pregnancy and a menstrual period that comes every 28 days. But they are basically the same thing. Women bleed every 28 days as a proof of missed pregnancy that was supposed to last for ten months. It is all about giving birth. Before discussing the obvious question of the status of “women” who no longer menstruate, I first want to call attention to these men’s association of women with materiality and the materiality with time. Women are watches that tick according to the changes taking place in their wombs. Yet, Mishima soon says, “Women exist within time” (my emphasis). If their bodies are time, how can women exist within time, as though they were separate entities? Mishima seems to unwittingly reveal that he and other men confine women within time. Likewise, in their association of women with the womb, they enclose women within the space/time confines of their womb clock. The little space in their bodies engulfs and traps them.

Mishima and Terayama suggest that, unlike women, men exist outside of time. That is, men exist outside of their bodies. They lack a womb clock, and so they lack a body. They are “accidental beings” as opposed to women as concrete beings, reminiscent of the Platonic model of Man/Ideal and Woman/Matter. Men’s search for outside watches mentioned by Terayama is in one sense (heterosexually) practical, as it seems to allude to copulation of men and women leading to reproduction. Men need women to give materiality to their own copies. But there is also something, maybe something heroic, in Terayama’s idea of men strolling around in search of watches/bodies: men floating around freely without being trapped by time and body/space. Nothing can nail them down. Their search for adventure is never-ending, because the very definition of men depends on their status as “accidental beings.” Once they have obtained watches/bodies, it makes them non-men. So, men are eternally free, while women are dragged down to the earth, probably until they stop ticking. Mishima and Terayama are too intoxicated with the idea of men’s eternal adventure to even think about what happens to women when they as watches stop ticking.4 Are they still women? Do they gain the rights to enjoy floating like men? Or, are they simply broken watches?

This chapter explores the ways in which the artists of girls’ aesthetics reconfigure such masculinist confinement of women into body/space and time. The above conversation between Mishima and Terayama took place in 1970, and this coincided with the time when postwar girls’ aesthetics were consolidated. The aesthetics challenged and continue to challenge the stereotypical view of women typified in these men’s conversation. The works discussed are performance troupe YUBIWA Hotel’s Lear (2004), performance troupe NOISE’s DOLL (1983), and visual artist Yanagi Miwa’s video installation piece Granddaughters (2002 and 2003). These works portray “girls” who reconceptualize the confinement they are forced to enter. They further imagine freezing time to reject becoming future wombs. At the same time, they also de-materialize the womb itself. In the masculinist discourse, women are enclosed in the womb as body/space, but the girls reimagine such a space as the one in which they dwell eternally as images without materiality. They let themselves be impregnated by this womb without temporalities.

Space and time in girls’ aesthetics

Before discussing these artists’ works, we will look at the historical context surrounding girls’ aesthetics, with a special focus on how they perceive space and time. While this monograph focuses on contemporary performance and visual arts that utilize these aesthetics, it is important to realize that they originated over a century ago in the early 1900s. As we will see in this chapter and the ones to follow, the fundamental traits of these aesthetics remain unchanged while there are shifts in the ways they are manifested. Considering that these aesthetics emerged as a resistance to the dominant gender and sexual ideology in the modern period, their continuation suggests that the ideology remains deeply rooted in contemporary society.

The category of “girls” is a modern construct in Japan. In the pre-modern or the pre-Meiji period,5 people were simply divided into children and adults, but the development of capitalism during the modernization process created a new category of adolescence, during which those between childhood and adulthood were trained or invested in to become the future labor force (Treat 1996: 280). The investment in this process took place at school. In 1872, the government issued an ordinance requiring all children to receive four years of education. Although it originally aimed at educating all Japanese citizens, education as a means of investment soon started to reflect the gender divide in the state’s strategies for managing its population. In 1879, the government issued another ordinance to separate women’s and men’s education beyond elementary school (Mackie 2003: 25), and in 1899, each prefecture was mandated to have at least one girls’ higher school (that is, school with three to five years of education for female students after elementary education) (Mackie 2003: 25; Honda 1983: 213). Honda Masuko explains that this process exemplifies the fact that the government assumed that educating female students would not provide as high a return on investment as it would with their male counterparts who after graduation would work in the military and industry. Young women were defined as those who would not appear in the public arena in the future, and it is these women who formed the social category of girls (Honda 1983: 214–15). Girls (shōjo) were thus synonymous with schoolgirls (jogakusei). They were not entitled to receive the same education as boys, but they were able to attend higher schools. What this meant in reality was that the social category of girls was defined as being only those young women whose families were wealthy enough to send their daughters to higher schools. It may be said that, in an expanding capitalist system, “girls” were a commodity that only the wealthy could afford.

Instead of providing future access to the public domain, the government determined that girls should become future guardians of the private sphere. Girls were designated as future “good wives, wise mothers” (ryōsai kenbo) who would represent the moral core of the expanding middle class (Honda 1983: 214–15) and, I would add, as reproducers of loyal Japanese citizens in the process of Japan’s nation-building. Adult women from “good” families were expected to serve their husbands, who were the heads of the households, and these households were considered to be miniature versions of family-state Japan.6 Women were to sustain these smaller versions of Japan and in turn the nation itself by giving birth to and educating (male) Japanese citizens, who would work for the Emperor in his effort to expand Imperial Japan’s national territory. Girls’ schools were established as reservoirs of those who would be the paragons of this state-sanctioned womanhood characterized by qualities such as “grace, elegance, gentleness, and chastity” (Honda 1982: 213). Indeed, the Japanese word for girl is shōjo, which literally means “not-quite-female female” (Robertson 1998: 65). Girls’ schools were the places where these “not-quite-female female[s]” were supposed to learn how to be fully fledged, nationalist females. Until they became such women, they were isolated from the rest of the society to remain “pure.”

Thus, girls were enclosed in schools with their sexuality surveilled under the gendered capitalist logic. Nevertheless, capitalism simultaneously opened up a space for their internal rebellion. Barbara Satō suggests that the consumerism in early-twentieth-century Japan brought empowerment at least to middle-class women; as the decision-making agents, these women actively constructed new images of themselves and demanded that their voices be reflected in a broader social context opened to them by the mass media (2003: 16–19). Likewise, schoolgirls experienced empowerment as consumers. Magazines targeting them started to be published in the 1900s. These magazines contributed to the emergence of an aesthetic category of “girls,” and became the primary site for the development of resistant girls’ aesthetics.

The girls’ magazines did not openly confront state-sanctioned womanhood. Rather, their official policy was in alliance with state policy – to educate future “good wives, wise mothers.” However, the editorial policy of these magazines was (possibly intentionally) ambivalent. While they preached conservative morality, they also functioned as a space for schoolgirls to collectively perform their fictional selves, ignoring the hegemonic gender and sexual ideology. For instance, girls communicated with other girls through the readers’ columns where they often used beautiful pen names such as Harunami (spring wave) or Shin’yō (heart leaf), as if to leave their material reality behind (Honda 1983: 225–7). They also described the images of their everlastingly young and beautiful bourgeois bodies, which would not produce anything, including offspring. In prose pieces that they sent to magazines, they celebrated such bodies in a sensuous and narcissistic way, using romantic and decorative phrases such as “a water drop running down the slightly flushed cheek after the bath” and “touching a sweet and sour stem [of flower] with lovely lips” (Kawamura 1993: 55). Their erotic desire was often directed towards other girls (Kawamura 1993: 61–4). Moreover, they even fantasized death as the ultimate way to freeze time and remain young (Kawamura 1993: 64–6).7 All these desires seeped out in the settings of girls’ schools, which were detached from the rest of the world. In/through girls’ magazines, girls thus reconfigured the closed domain of sexual surveillance at girls’ schools as a resistant space. This imaginative reconfiguration was motivated by the fact that they were exempted from wifehood and motherhood during their studentship, even though their bodies were “mature” enough for these roles. Girls thus indulged themselves in an “ahistorical ‘now’” (Honda 1982: 220) in the closed space open only for them. Therefore, unlike the first-wave feminists, such as the members of the first Japanese feminist group, Seitō (Bluestocking), formed in 1911, girls did not attempt to transgress the boundary between the public and the private spheres. Rather, their rebellion took the form of isolating themselves from the reality they lived in. They twisted the function of the private sphere, or more precisely a liminal sphere between their home and society, in their imagination. This strategy of twisting the function of their surroundings has been the fundamental trait of girls’ aesthetics ever since.

Although girls’ aesthetics primarily advocate the fictionality of girls in a closed space without temporalities, they were also expressed by actions in the “real” world, which blurred the boundary between fiction and reality. For example, there were several cases of double suicides among girls, which became fodder for scandal in the mass media. The first reported case took place in 1911, where two graduates of a girls’ school in Niigata Prefecture killed themselves in despair at not being able to continue their romantic relationship in heteronormative society after graduation (Suzuki 2010: 24; Akaeda 2011: 104). Akaeda Kanako reports that there were also frequent double suicides of this kind around this time, with the peak from the late 1920s to the mid 1930s (2011: 107). These cases suggest that girls’ desire to freeze time and to discard their material bodies is closely linked to their rejection of adulthood-cum-heteronormativity. The incidents further confused the public ideas of “pure” friendships and pathologized romantic relationships between girls (Suzuki 2010: 25; Akaeda 2011: 110–11). This suggests that, while girls’ schools were primarily seen as safe places to protect girls’ virginity, there existed some anxiety over confining them in these institutions.

Girls’ aesthetics during wartime and the immediate postwar period will be discussed in the chapters to follow, and therefore I will briefly consider only a few important points here. The tradition of these aesthetics did not die out even during wartime, despite the increasing pressure from the government to remove girlie images from the girls’ magazines and instead to portray stout and healthy female adolescents who could protect the home front. After the war, “democratic” co-education was instituted by the US Occupation (1945–52); however, while girls faced a new heterosocial environment, many did not let go of these aesthetics. It seems that one of the ways in which they dealt with the change in their everyday reality was to feminize male students and include them in their imaginary girlie sphere. This is demonstrated by girls’ magazines from this time, in which male students were depicted with stereotypically feminine gender and sex markers such as colored lips and long eyelashes (see Chapter 2 for more discussion).

The unprecedented magnitude of the consumer society of the 1970s brought what Ōtsuka Eiji, a subculture and girls’ studies theorist, calls “the big bang of girls’ culture” (1989: 49). So-called kawaii (cute) culture burgeoned in this period, and the industry for cute items such as stuffed animals and frilly dresses rapidly bloomed. After the recovery from the devastation in the war, girls were rediscovered as consumers. Moreover, the category of schoolgirls became more mainstream, as more and more women started to have at least a high-school education. In 1970, the percentage of women who went on to high schools exceeded 80 percent for the first time (Tōkei kyoku [Statistics Bureau] 2005). Prewar girls’ aesthetics were lar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Girls’ Aesthetics

- 1 Girls’ Time, Girls’ Space

- 2 Girlie Sexuality: When Flat Girls Become Three-Dimensional

- 3 Citizen Girls

- 4 “Little Girls” Go West?

- Afterword: Girls’ Aesthetics as Feminist Practices

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index