eBook - ePub

Women, Rank, and Marriage in the British Aristocracy, 1485-2000

An Open Elite?

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Through an analysis of the marriage patterns of thousands of aristocratic women as well as an examination of diaries, letters, and memoirs, this book demonstrates that the sense of rank identity as manifested in these women's marriages remained remarkably stable for centuries, until it was finally shattered by the First World War.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Women, Rank, and Marriage in the British Aristocracy, 1485-2000 by K. Schutte in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de la Grande-Bretagne. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireSubtopic

Histoire de la Grande-BretagnePart I

The Statistical Side of the Story

At the heart of this project is the data set of the marriages of thousands of the daughters of aristocratic families over the extended period from 1485 to 2000. It is remarkable what a relatively simple collection and analysis of that much data can reveal. The chapters in Part I of this book have at their center the statistical analysis of that data. Using those numbers, the following chapters will examine the tendency toward endogamy, exogamy, hypogamy, and unmarriedness as well as the rate of British (that is, cross-national) marriage, and the openness of the British aristocracy.

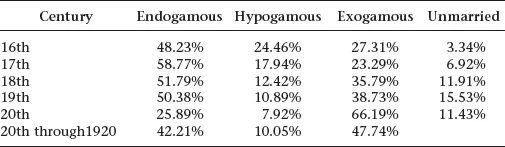

The basic numbers reflecting these patterns are to be found in Tables I.1 and I.2:

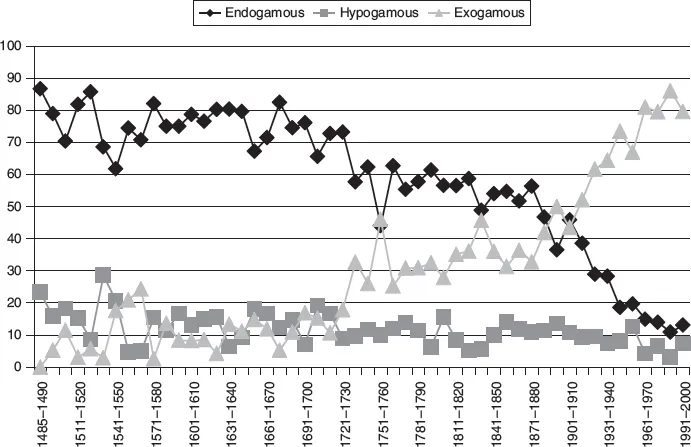

These Tables show the remarkable stability in the patterns in the period from 1485 to the period between 1880 and1920 reflecting a parallel stability in the self-perception of aristocratic rank identity in that period.

Table I.1 Basic British Marriage Patterns

Statistical information, unless otherwise indicated, is based on the data collected and analyzed by the author. These figures are generated by dividing the number of each type of marriage by the total number of marriages in the century. The figures for the Unmarried column are generated by dividing the number of women who remained unmarried by the total number of women who attained marriageable age (at least 22) in the century.

Table I.2 Marriage Patterns by Decade

In his important study, The Family, Sex, and Marriage in England, Lawrence Stone points out that all strata of early modern English society married within a very limited social range. The custom of the dowry, together with the great sensitivity to status and rank, meant that the aristocracy tended to marry their social and economic peers.1 David Cannadine in The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy argues that the last two decades of the nineteenth century witnessed a reduction in endogamous marriages; he contends that “at the very time that society was becoming more plutocratic, the peerage was becoming more plebeian.”2 Cannadine states that the number of endogamous marriages undertaken by the nineteenth-century aristocracy declined sharply and he gives several examples of marriages between plutocratic and aristocratic families. His study focuses on the marriages of aristocratic males and finds a rather sharp break in the pattern of their behavior. When the marriages of aristocratic females are examined one does find somewhat the same pattern; though it is more complicated than that described by Cannadine. In the period between 1880 and 1920, the number of elite women marrying endogamously began to drop while the number marrying exogamously increased.3 Despite this change, which is in line with the Cannadine findings, the overall pattern of constancy remained essentially intact until the end of the First World War.4 This project does not undermine the findings of Stone and Cannadine, but rather it shows that the question of aristocratic rank identity is more complex when the factors of gender and extended time period are considered.

1

The Basic Marriage Patterns

This chapter sets out and interrogates the basic marriage patterns of British aristocratic women from 1485 to 2000. At its most fundamental it looks at the rates of endogamy, hypogamy, exogamy, and unmarriedness. The primary argument here is that the constancy in the rates of endogamous and exogamous marriages between 1485 and 1880–1920 indicates that there was a constancy in the self-understanding of noble rank identity during that period as well; a constancy that was shattered by the First World War. The hypogamy rate dropped sharply with the introduction of the baronet and remained extraordinarily low from the seventeenth century through the end of the twentieth, a rate that is so low as to indicate a distinct prejudice among the titled ranks against grooms from that level. The level of unmarriedness also provides an window into understandings of rank identity and the means of preserving such identity; beginning in the eighteenth century the percentage of elite women remaining unmarried sharply increased (a trend that continued through the end of the nineteenth century) indicating a belief that it was better for a woman of this rank to remain unmarried rather than marry below her rank, a belief that points to the idea that rank identity was essentially personified in the women.

Endogamy

For much of the period under consideration here the natal families of aristocratic women often treated them as little more than cogs in their prestige-enhancing plans, resulting in a consistent push toward endogamy. The letters and journals of the women themselves repeatedly underscore the perceived need to marry well in conformity with the expectations of their families.1 Very frequently, they indicated that membership in the titled rank was among the most important attributes for a potential spouse. Following the dictates of duty, most elite women married husbands chosen by their families. The endogamy rate of the daughters of the British aristocracy remained remarkably stable from 1485 to 1880–1920.2 As is shown in Table I.1 above, the rate of shift in that period, when examined by century, remained within about 10 per cent.3 The pattern that emerges when examining the marriage rates decade-by-decade, as shown in Table I.2, is far more stable, with nearly none of the shifts rising to the level of statistical significance. This consistency is all the more remarkable when considering the social, economic, and political transformations of the period. Despite the great changes that affected Britain, the importance of maintaining rank identity among the nobility remained quite static. That social group maintained a strong sense of cohesion and stable identity for a period of nearly 450 years.

Statistics demonstrate a strong, though not overwhelming, tendency of aristocratic women to marry within rank, as just over 50 per cent of the marriages of these women were endogamous. The written evidence nearly always presents endogamous marriage as being of far greater importance than the actual marriage patterns demonstrate; the evidence found in the letters and memoirs of aristocratic women from 1485 to 2000 reveals the consistently high value they placed upon rank and its role in the marriages of women of their rank. The commentary found in their written remains indicates a social attitude that nearly always made endogamy a goal.

Though the drive toward endogamy was remarkably stable for nearly five centuries, the statistics compiled for this study indicate that the seventeenth century was the most rank-conscious century as indicated by the endogamous marriages of its noble women. The daughters of seventeenth-century aristocrats married inside titled ranks 58.77 per cent of the time as compared to the next highest rate of 51.79 per cent for the eighteenth century.4 They also had the lowest rate of exogamous marriage: 23.29 per cent as compared to the next lowest rate of 27.31 per cent for the sixteenth century.5 An analysis of those seventeenth-century marriages for which a specific date is available shows little fluctuation in the rates of endogamy over the century, so the pattern does not appear to have any relationship to the political turbulence of civil war, interregnum, and restoration.6 The rate of endogamous marriage fell off in the eighteenth century to 51.79 per cent, a level that still remained well higher than the 48.23 per cent of the sixteenth century. In the very upper strata of society, the strong inclination was still to marry endogamously.

That inclination increased the higher a woman was in the titular hierarchy. In all of the centuries, except the sixteenth, the daughters of marquesses and dukes were significantly more likely to marry a man from the titled aristocracy than were the daughters of barons, viscounts, and earls. In the sixteenth century the daughters of the upper two levels of the hierarchy married endogamously 53.48 per cent of the time while those of the lower levels did so 50.32 per cent of the time. In the seventeenth century, not surprisingly, both of those rates increased, to 84.25 per cent for the higher ranks and 52 per cent for the lower. The in-marriage rates of both tiers slipped back a bit in the eighteenth century to 43.61 per cent for the daughters of the lesser nobility and 69.49 per cent for those born to marquesses and dukes. In the nineteenth century the percentage of marriages from the lower tier that were endogamous increased slightly to 45.5 per cent while those of the upper tier dropped significantly to 57.18 per cent. In the first two decades of the twentieth century the upper tier married endogamously 62.43 per cent of the time while only 38.66 per cent of the lower tier marriages were to titled grooms; it appears that the precipitous drop in endogamy that characterized the twentieth century as a whole began somewhat earlier in the lower levels of the nobility.7

The higher levels of endogamy among the daughters of marquesses and dukes is not surprising as those families at the upper levels in the aristocracy generally would have had the means and the prestige to make their daughters attractive mates to others of noble rank at all levels in the hierarchy. A duke’s daughter was a good catch for any family, while a baron’s daughter would need a substantial dowry to make her appealing to a marquess. These higher titles likely would also have a stronger sense of rank identity that would also prompt them to seek titled husbands for their daughters.

From at least the late eighteenth century, aristocratic women functioned as the personification of their rank; families could safely consider themselves aristocratic if at least one of their daughters married within rank (or failing that did not marry at all) no matter whom their sons might marry. When the emphasis is on the marriage patterns of the women, it becomes evident that social rank identification among aristocratic women remained vital throughout the long nineteenth century. The motivations toward marriage can be seen as essentially gendered. Aristocratic men married for reasons that differed from those of aristocratic women. It became the role of the women of this rank to maintain the sense of rank identity. One of the primary ways by which they did so was through their marriage choices and the marriages that they arranged for members of their families. The changing mores of society and the unchanging expectations of the aristocracy in the nineteenth century placed these women in a difficult position. They were very much a group under pressure in the latter centuries of this study.

National Trends

The picture concerning the ongoing trend toward endogamy is somewhat altered when the data is separated by nation rather than by time frame. The marital patterns of the British nations over the period from 1485 to 2000 differed from one another.8 These differences indicate that the attitudes toward rank in England, Ireland, and Scotland were perhaps somewhat variable as compared to one another. England had a relatively low rate of endogamous marriage in the sixteenth century and then it rose and held quite steady from the seventeenth through the nineteenth century,9 with a significant drop (though still not back down to sixteenth-century levels) in the first two decades of the twentieth century.10 English levels of exogamy steadily increased, except for a drop in the seventeenth century, through the twentieth century. The Scottish pattern was essentially the same as the English. The Irish followed a path of their own, likely due to their experiences with English domination and the imposition of a largely foreign aristocracy. Unlike the other nations, the Irish were far more prone to marry endogamously in the sixteenth century than at any other time. This is likely due to the fact that it was in the latter part of the sixteenth century that the English began to replace the native aristocracy with their own appointees. All statistics, except the specifically Irish data set, show that the seventeenth century was the most rank conscious as evidenced by the higher endogamy rate. In Ireland, the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries show a proportionally lower rate of endogamy and higher rate of exogamy. It seems most likely that this anomalous downward trend in the Irish patterns had a great deal to do with the heavy depredations suffered by that country during the War of the Three Kingdoms. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Ireland was subject to English rule and this situation had a profound impact on the make-up of the Irish aristocracy. The crown gave Irish titles to many English that, while certainly noble, were not seen as the equivalent of English or Scottish peerages. It was, then, more difficult for the Irish peerage to marry within rank. The fact that the Irish peerage was smaller than e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Marriages of Aristocratic British Women and Stability of Rank Identity, 1485–2000

- Prologue: Identity and Rank

- Part I The Statistical Side of the Story

- Part II The Less Statistical Aspects of the Story

- Conclusion

- Biographical Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index