This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The book investigates the substance of the European Union's (EU) democracy promotion policy. It focuses on elections, civil and political rights, horizontal accountability, effective power to govern, stateness, state administrative capacity, civil society, and socio-economic context as components of embedded liberal democracy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Substance of EU Democracy Promotion by A. Wetzel, J. Orbie, A. Wetzel,J. Orbie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Trade & Tariffs. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Substance of EU Democracy Promotion: Introduction and Conceptual Framework

Anne Wetzel

When, in October 2009, the European Parliament adopted its resolution on democracy building in the European Union’s (EU) external relations, it urged the EU ‘to publicly endorse the UN General Assembly’s 2005 definition of democracy as the reference point for its own democratisation work’ (European Parliament 2009: Art. 7). This call is remarkable because it exemplifies the thin conceptual basis of EU democracy promotion. At that time, it represented a further step in ongoing attempts to define the meaning of ‘democracy’ in EU external actions. Eventually, however, the call went unheard. To this day, the EU has not (yet) accepted a single definition of democracy that guides its democracy promotion activities. Scholars have recently come to the conclusion that the conceptual basis of EU democracy promotion can be summarized as ‘fuzzy liberalism’ (see the chapter by Milja Kurki in this edited volume).

Against this background, the question that guides this edited volume is what the EU promotes in the absence of a clear conceptual basis for its democracy promotion policy and how we can explain the content of EU democracy promotion. This is relevant for several reasons. The EU is one of the world’s major democracy promoters.1 As Michael Meyer-Resende, Director of Democracy Reporting International, and Dick Toornstra, Director of the Office for Promotion of Parliamentary Democracy (OPPD) at the European Parliament, state, ‘[c]larity on what Europe means by “democracy” would be in the interest of transparency and fairness towards foreign partners’ (2009). Mapping the substance of EU democracy promotion contributes to such transparency. At the same time, knowing what the EU aims to promote is fundamental when it comes to the assessment of its success as a democracy promoter. Finally, the study of the substance of EU democracy promotion and the factors that shape this substance contributes to our understanding of the EU as an international actor more generally. Given the unique nature of the EU’s internal system of governance (Laffan 1998), the question emerges: which values does the EU further outside its territory and which factors contribute to shaping this substance?

The book contributes to a new research agenda on the substance of democracy promotion by systematically mapping the substance of EU democracy promotion and explaining it. It deals with the substantive, democracy-related content that is being promoted by the EU towards third countries through various activities. In doing so, it partly builds on the results of earlier exploratory works on the substance of EU democracy promotion (Wetzel and Orbie 2011a).

The analysis starts from a puzzling finding of the existing literature. While the EU is found to promote liberal democracy in general, it is at the same time often accused of neglecting liberal democracy’s core values in its concrete democracy promotion activities. Taking this dual finding as a point of departure, the book employs an adapted model of embedded liberal democracy for mapping the substance of EU democracy promotion. This model is employed in relation to 22 country case studies. In addition, the volume advances hypotheses about the factors that determine this substance. It elaborates on the expectations that the substance may be shaped by (a) the differences in power between the EU and a target country; (b) EU internal institutional factors; (c) differences in the target countries’ domestic contexts; and (d) differences in the interorganizational field in the third country. These hypotheses are addressed in all of the country case chapters. Finally, since democracy is a contested concept and the focus on embedded liberal democracy implies a neglect of other forms of democracy (Schimmelfennig 2011), the book includes four contributions to the discussion from the angles of law, critical theory, political economy and governance that put the framework into perspective by offering alternative takes on the substance of democracy promotion. While these elaborations cannot be exhaustive, they do indicate avenues for further research on the topic.

This introductory chapter presents a short review of the literature that guided the choice of the adapted model of embedded democracy. This model is presented in the subsequent section of the chapter. In the third part of the chapter, hypotheses on the substance of democracy promotion are developed and concepts are operationalized. Finally, the chapter provides an outline of the structure of the book and of our case selection.

The substance of EU democracy promotion: Some puzzling evidence

Despite the abundant literature on EU democracy promotion (for example Jünemann and Knodt 2007, Magen et al. 2009, Youngs 2010a), its substance has received little systematic attention. When scholars address substance, they come to different conclusions about its nature. On a general level, the EU is found to promote liberal democracy (Carothers 1997, Ayers 2008: 3, Risse 2009: 249, Kurki 2010). In a remarkable number of cases, however, the EU seems to neglect the classical elements of liberal democracy (such as civil and political freedoms, checks and balances; see for example Held 2006: 56–95). Youngs and Pishchikova, for instance, characterize EU democracy promotion as tending towards ‘a technocratic, rules-export, governance focus’ (2013: 25). Similarly, Hout summarizes that the governance-related strategies of EU development policy ‘display a technocratic orientation and are instrumental to deepening market-based reform in aid receiving countries’ (2010: 3). Holden analyses the EU’s democracy promotion policy in the Middle East and comes to the conclusion that the EU promotes hegemonic polyarchy, the major thrust of which consists of ‘neo-liberal reform, the opening of markets, and legal and economic integration’ (2010: 608). Huber, in turn, sees a clear dominance of state-capacity building measures in the EU’s democracy assistance in the Middle East and North Africa (2008: 53). These findings are also supported by Reynaert’s study on the EU’s policy towards the Southern Mediterranean countries, which concludes that ‘the promotion of the civil society, the functioning of the state, and the core elements of democracy are oriented to the promotion of a market-based economy’ (2011a: 623). As a result, the EU is found to focus on the promotion of a good governance agenda (Reynaert 2011a: 637). Carothers sees European democracy promotion as following a ‘developmental approach’, which gives emphasis to socio-economic concerns, state capacity and good governance (2009). Börzel’s work, which compares a wide range of target countries, suggests that the question of substance is not one of ‘either/or’, but of gradation. She finds remarkable variation in the EU’s activities, ranging from the promotion of reforms related to input legitimacy and supporting democratic government or governance to reforms related to output legitimacy and thus more to effectiveness (2009).

In order to take these findings into account, we adopt an adapted model of embedded liberal democracy comprising both the core elements of liberal democracy and elements such as state capacity, governance and civil society that have been highlighted by some researchers.

Mapping the substance of EU democracy promotion

Against the background of the above-mentioned dual finding regarding the content of EU democracy promotion activities, we take the democracy models developed by Linz and Stepan (1996a) and Merkel (2004) as a point of departure for the mapping exercise.2 These works are particularly suitable because they offer a broad conceptualization of liberal democracy.3 They encompass interlocking core institutions of democracy and supporting external conditions, both of which have been found to be important elements of EU democracy promotion. At the same time, these models allow us to keep core conditions and enhancing external conditions conceptually separate.

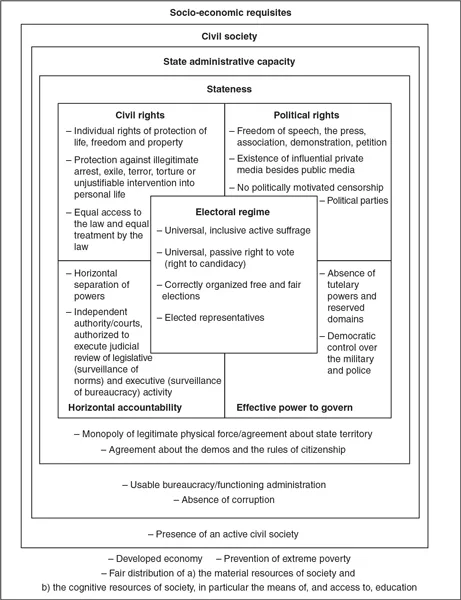

Although the two conceptualizations overlap, they also differ, in particular with regard to the question of whether some issues belong to the definitional core or the context of democracy, and the fine-graining of categories. For Linz and Stepan, the five conditions for a democracy are civil society, political society, rule of law, state apparatus and economic society. Democracy, in turn, is dependent on the existence of a state (Linz and Stepan 1996a: ch. 1). Merkel’s model of embedded democracy maintains that ‘liberal democracy consists of five partial regimes: a democratic electoral regime, political rights of participation, civil rights, horizontal accountability, and the guarantee that the effective power to govern lies in the hands of democratically elected representatives’ (Merkel 2004: 37). Furthermore, it accounts for requisites that have an influence on the quality of democracy but ‘are not defining components of the democratic regime itself’ (Merkel 2004: 44). Figure 1.1 illustrates the concept.

With a view to our aim of mapping the substance of EU democracy promotion, we have decided to mainly follow Merkel’s model, but adapt it with a view to aspects of Linz and Stepan’s conceptualization of the five areas. This was done for several reasons. First, Merkel’s model is more accurate for our purposes here. For instance, it allows us to distinguish more clearly between civil rights and civil society and to disaggregate complex issues such as the rule of law. Also, a major advantage in view of the domestic context hypothesis is that the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI 2012a, 2012b) follows this model and can thus be applied in almost all country chapters. Secondly, we do not follow Linz and Stepan’s suggestion of including an institutionalized market in the definition of democracy but rather see them as distinct issues (cf. Beetham 1997; for a discussion of the relationship between democracy and economy see also Kurki’s contribution to this edited volume). Thirdly, Merkel’s model helps to clarify the distinction between core aspects of liberal democracy and some related elements that emerge from the literature review and thus may eventually help to account for the diverse findings in the literature. We have modified Merkel’s original model in that we have explicitly added the element of stateness and have included state bureaucracy from Linz and Stepan’s conceptualization. In the following paragraphs, we briefly summarize the five partial regimes and four context conditions along which we will structure our analysis of the substance of EU democracy promotion (for the next paragraphs, see Merkel 2004: 38–9).

Figure 1.1 The concept of embedded democracy

Source: Adapted, based on Merkel (2004: 37).

The electoral regime has the central position of the five partial regimes since it is necessary, but not sufficient, for democratic governing. Following Dahl, Merkel outlines four supporting elements of this regime: universal, active suffrage; universal, passive right to vote; free and fair elections; and elected representatives. The most closely connected partial regime is constituted by the political liberties that go beyond the right to vote. Most basically, they include the right to political communication and organization, that is, press freedom and the right to association. These define how meaningful the process of preference formation is in the public arena. The third partial regime consists of civil rights that are central to the rule of law, that is, the ‘containment and limitation of the exercise of state power’ (Merkel 2004: 39). Most fundamentally, this includes that individual liberties are not violated by the state, and equality before the law. Related to this is the existence of independent courts. The fourth connected partial regime consists of divisions of power and horizontal accountability. This implies that ‘elected authorities are surveyed by a network of relatively autonomous institutions and may be pinned down to constitutionally defined lawful action’ (Merkel 2004: 40; see also Morlino 2004: 18). The horizontal separation of powers thus amends the vertical control mechanisms of elections and the public sphere. Particular emphasis is put on the limitations to executive power. Central to this partial regime is the existence of an independent and functional judiciary to review executive and legislative acts. The last partial regime is the effective power to govern. This means that it is the elected representatives that actually govern and that actors not subject to democratic accountability should not hold decision-making power. In particular, there should be no tutelary powers or reserved policy domains (Merkel 2004: 41–2; see also Valenzuela 1992: 62–6).

While these five partial regimes are understood to be the defining components of a democracy, there are some more conditions that, while not part of the definition itself, shape the ‘environment that encompasses, enables, and stabilizes the democratic regime’ (Merkel 2004: 44). Damage to these conditions might lead to defects in, or the destabilization of, democracy. However, it is important to add that the promotion of the external conditions alone does not necessarily further democratization. On the contrary, a sole focus on the context conditions can even be to the detriment of democratization (for example, Fukuyama 2005: 87–8).

The first of the external supporting conditions is stateness, understood as the ability of the state to pursue the monopoly of legitimate physical force. Where the monopoly of authority and physical force is not institutionalized, it cannot be democratized (Merkel et al. 2003: 58). Following Linz and Stepan, a state is indispensable for democracy: ‘No state, no democracy’ (1996b: 14). Although this strict connection between state and democracy can be disputed (Beetham 1999: 4–5), it is consistent with the traditional liberal democratic definitions of democracy that focus on ‘governmental activity and institutions’ at the state level (Held 2006: 77). Stateness is seen to be problematic when the territorial boundaries and the eligibility for citizenship are disputed (Linz and Stepan 1996: ch. 2). It also ‘implies that the organs of the state uphold monopolistic control in a basic military, legal, and fiscal sense’ and that there are no competing power centres exercising control in these areas (Bäck and Hadenius 2008: 3).

The second external context condition, which, in contrast to Merkel’s original framework and our own earlier work, we have separated from stateness, is state administrative capacity. It refers to a capable administration. As Linz and Stepan put it, democracy relies on ‘the effective capacity to command, regulate, and extract’. The bureaucracy must be usable by the democratic government (Linz and Stepan 1996: 11). In a broader sense, this condition refers to good governance, in particular to the output-related understanding. It includes in particular the effective government component of good governance promotion, which deals with the ‘administrative core of good governance’ and implies ‘improving governance through strengthening the government and its administration’ (Börzel et al. 2008: 10).

The third external context condition is the presence of civil society. This is the ‘arena of the polity where self-organizing groups, movements, and individuals, relatively autonomously from the state, attempt to articulate values, create associations and solidarities, and advance their interests’ (Linz and Stepan 1996: 7). The importance of this context condition stems from the assumption that a well-developed civil society strengthens democracy by generating and enabling ‘checks of power, responsibility, societal inclusion, tolerance, fairness, trust, cooperation, and often also the efficient implementation of accepted political programs’ (Merkel 2004: 47). The promotion of civil society is often seen as a part of good governance promotion and can be both input and output-oriented. While the former orientation stresses the empowerment of non-state actors in policy-making ‘in order to improve the democratic quality of decision-making processes’, the latter refers to the strengthening and/or inclusion of non-state actors in the policy implementation process with the aim of either producing better policies or better implementing policies. The case studies will, as far as possible, indicate which orientation EU civil society promotion follows in each specific instance (Börzel et al. 2008: 10).

The fourth external condition that has an influence on the state of democracy is the socio-economic context. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 1. The Substance of EU Democracy Promotion: Introduction and Conceptual Framework

- Part I: Alternative Reflections on the EU as a Liberal Democracy Promoter

- Part II: Country Chapters

- Annex: Summary of Substance and BTI Values

- References

- Index