This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Through critical analysis of key concepts and measures of the rule of law, this book shows that the choice of definitions and measures affects descriptive and explanatory findings about nomocracy. It argues a constitutionalist legacy from centuries ago explains why European civilizations display higher adherence to rule of law than other countries.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Rule of Law by J. Møller,S. Skaaning in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

On Definitions

1

Systematizing Thin and Thick Rule of Law Definitions

In the Introduction, we made the observation that the rule of law is a generally acknowledged political ideal. However, we also made it clear that the universal recognition of the merits of the rule of law has in no way been accompanied by a universally accepted definition of it. On the contrary, different people mean very different things when employing the term (Trebilcock and Daniels, 2008, pp. 12–13). More particularly, one of the main problems burdening the rule of law research agenda is that the term is oftentimes employed without justifying or even spelling out the definition, and – partly as a consequence – without selecting empirical measures that match the stipulated (or intended) definition. Such nonchalance is problematical because the establishment of a technical language based on sound logical premises is a prerequisite for rigorous and cumulative research (Sartori, 1970). This, in turn, demands that the competing definitions are clarified and ordered.

This is the objective of the present chapter. On the pages that follow, we provide a panoramic view of rule of law definitions in the literature, based on the systematic guidelines that have been developed in political science over the latest decades (see, e.g., Sartori, 1970, 1984; Collier and Mahon, 1993; Adcock and Collier, 2001; Munck and Verkuilen, 2002; Gerring, 1999; Goertz, 2006).

Mapping the principal definitions

How may we systematically map the dominant definitions of the rule of law? Sartori’s (1984, p. 41) advice is to ‘first collect a representative set of definitions; second, extract their characteristics; and third, construct matrixes that organize such characteristics meaningfully’. The first two steps entail a careful review of the literature and a subsequent disaggregation of the identified definitions. In line with Bedner (2010, p. 55), we see this two-fold exercise ‘as purely heuristic: its argument is not that certain elements ought to be part of the rule of law concept, but rather which elements are claimed to be part of it according to the literature.’ Regarding the third step, we turn to Munck and Verkuilen’s (2002) notion of a tree-like conceptual structure, in which the concept is divided into its constituent dimensions, which are again divided into their constituent attributes and sub-components.1

The concept of the rule of law is highly complex and essentially contested. Thus, it is hardly surprising that ‘much confusion over the meaning, aims, means and successes of rule of law promotion is currently prevalent among politicians, diplomats, and other practitioners’ and that ‘academia, if anything, is as much divided over the meaning and aims of the rule of law as practice’ (HiiL, 2007, p. 9). Confronted with such conceptual ambiguity, the radical solution is to abandon the concept altogether and proceed in a more disaggregated way, that is, to drill down to particular sub-components such as, say, judicial independence (cf. Ríos-Figuera and Staton, 2012). However, there is an obvious danger of throwing the baby out with the bathwater here. Although essentially contested, the concept of the rule of law is almost certainly here to stay (Waldron, 2002). This is reflected in the fact that many theories make use of a general understanding of the rule of law rather than its individual components, and that it has become virtually unthinkable that the concept should no longer be part of academic vocabulary and the parlance of politicians, pundits, and journalists. What is needed is therefore to strengthen the conceptualization of the key concept rather than to abandon it.

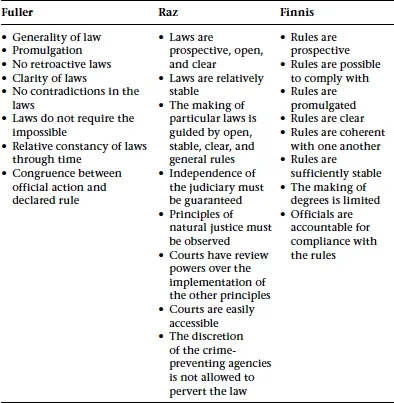

The first step of such an exercise is to sketch the common ground. Fuller (1969, p. 39), Raz (1979, pp. 214–18), and Finnis (1980, pp. 170–1) have offered some of the most prominent definitions of the rule of law. In Table 1.1 we have listed the core principles emphasized by these scholars.

As Table 1.1 shows, the conceptions of Fuller, Raz, and Finnis are strikingly similar. But two expansions of these conceptions are frequently singled out in the literature as necessary. The first is what Raz (1979, p. 212) identifies when writing that,

The ‘rule of law’ means literally what it says: the rule of the law. Taken in its broadest sense this means that people should obey the law and be ruled by it. But in political and legal theory it has come to be read in a narrower sense, that the government shall be ruled by the law and subject to it.

As the emphasis shows, the first additional dimension concerns order, requiring that members of the general public comply with the law. The second additional dimension regards a feature that, inter alia Lauth (2001, p. 33), includes in his list of general rule of law principles, namely equality under the law and before the courts.2 With these additions, all of the separate meanings of the phrase that are most commonly used today – as identified by Belton (2005; see also Fallon, 1997) – are covered, except for the thick notions of including various human rights and popular consent in law-making in the form of democracy (see below).

Table 1.1 Principles of the rule of law

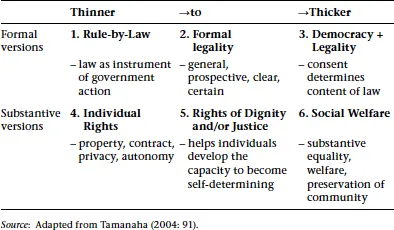

In what follows, our aim is to relate these conceptions to each other in a systematic fashion. Tamanaha (2004) has carried out a prior attempt to distinguish systematically between different definitions of the rule of law, which serves as our point of departure. Tamanaha distinguishes between formal and substantive definitions of the rule of law. Within each category he identifies a continuum between thin (more minimalist) and thick (more maximalist) definitions.3 Furthermore, he seems to argue that the two dimensions can be collapsed into one, as the substantive definitions explicitly or implicitly embed the attributes of the formal definitions. This comes out even more clearly in a later contribution of Tamanaha, in which thin is basically equated with ‘formal’ whereas thick is equated with ‘substantive’ (HiiL, 2007, p. 10). We return to the question of latent or intrinsic one-dimensionality in the following chapters. Tamanaha’s (2004, p. 91) overview is presented in Table 1.2 below.

At first sight, Tamanaha’s distinctions seem to mirror those encountered within democratic theory, in which the main demarcation line runs between procedural definitions – construing democracy as a political method defined by certain procedures – and substantive definitions – construing democracy in terms of its substance (Collier and Levitsky, 1996; Sørensen, 2007, pp. 10–16). However, things are not as simple with regard to the rule of law. Tellingly, in the later condensation of his thoughts on the subject, referred to above, Tamanaha (2007) displaces democracy to the substantive realm (HiiL, 2007). We concur with this decision, though not with the term denoting the dimension, as democracy (in its procedural form) is best defined as a set of political rights. As such, it is basically of the same ilk as other rights, such as civil and political freedom rights (O’Donnell, 2007). This goes to show that the adjective substantive has a very different meaning for Tamanaha than is the case within democratic theory. Indeed – somewhat paradoxically – it matches the dimension that democratic theorists term procedural.

Table 1.2 Tamanaha’s overview of alternative rule of law definitions

This makes for confusion, as the manifold and often very careful attempts to define democracy serve as the most obvious frame of reference for conceptualizing the rule of law. Instead, we propose a distinction between four different rule of law dimensions. The premise of this distinction is that the rule of law has to do with rules. What needs to be distinguished, however, is the shape of the rules, the sanctions of the rules, the source of the rules, and the substance of the rules. Using another easy-to-memorize alliteration, these dimensions can be rendered as core, control, consent, and content of the rule(s) of law, respectively.

The shape of the rules

The first dimension concerns the shape (or core) of the rules. Here, we retain Tamanaha’s distinction between rule by law on the one hand and formal legality on the other. Rule by law simply means that the exercise of power is carried out via positive law, something that – de jure – characterizes virtually every polity today. Formal legality, on the other hand, entails that the rules are general, prospective, clear, certain, and consistently applied. The former definition is obviously thinner – and subsumed by – the latter, as formal legality also entails that rulers exercise power via positive law but then adds certain requirements concerning the characteristics of these rules. In fact, rule by law is arguably the most minimalist definition within the literature.

More generally, the notion of formal legality relies on the maxim that ‘ought implies can’ (HiiL, 2007, pp. 15–17). If a subject ought to obey the laws – and that is the very crux of any rule of law understanding – then it must be possible for him/her to do so. That, in turn, requires that law has the properties of generality, prospectiveness, clarity, etc. These arguments are almost self-evident and it is unsurprising that the notion of formal legality has been hugely influential within the literature, promoted by scholars such as Hayek (1960, 1973), Fuller (1969), Raz (1979), and Finnis (1980). Tellingly, Rawls (1971, p. 235), in his path-breaking work on justice, writes that, ‘the conception of formal justice, the regular and impartial administration of public rules, becomes the rule of law when applied to the legal system’. Notice in this connection that we include consistent application as a constitutive sub-component of formal legality. Formal legality by definition includes consistency of application for the simple reason that (such) laws are general (Hayek, 1960, 1973). However, it does not necessarily embed the broader notion of equality before the law, which also entails that laws must not discriminate across generally defined groups.

The sanctions of the rules

The next dimension concerns the sanctions of the rules; what we also refer to as ‘control’. A very influential aspect of the rule of law is contained in this dimension. It regards the medieval doctrine of the supremacy of law: that laws – not men – rule (Fukuyama, 2010). At the extreme, this means that the sovereign is not a lawgiver, as all laws are found, not made. This is the Western understanding of law that emerged in the Middle Ages (Bloch, 1971a [1939]; Myers, 1975) and which, according to some scholars, represents the basis for modern democracy (Downing, 1992).

The extreme version of this medieval notion obviously has little present import. However, the notion of the supremacy of law exists in a different form. In the contemporary world, the supremacy of law entails that the sovereign lawgiver is bound by higher laws, such as those of present-day constitutions, and that an effective separation of power keeps the rulers checked (Hamilton et al., 1987 [1787/1788]). This dimension can be understood in terms of the concept of horizontal accountability (cf. O’Donnell, 2007). Its institutional manifestation is a system of checks and balances, such as an independent judiciary and penalties for misconduct, ensuring that the government and its agents (including bureaucrats) abide by the law.

The source of the rules

The third dimension in our conceptual overview is the source of the rules. Under this dimension we place Tamanaha’s (2004) notion of consent, meaning that democracy in the guise of the sovereignty of the people is the source of the laws. Needless to say, this tradition also figures prominently within Western thought. Indeed, to some extent it also can be traced back to the Medieval milieu, as the contractual character of feudalism gave birth to the political notion of the ‘right of resistance’, present as early as the Oaths of Strasbourg in 842, and subsequently reconfirmed in, for example, the Magna Carta of 1215 and the Hungarian ‘Golden Bull’ of 1222 (Bloch, 1971b [1939], pp. 451–2) (see Chapter 8).

However, in its present version the attribute of consent can be traced to the classical liberal tradition, inaugurated by Locke (1993 [1689]). For this attribute to make sense, conceptually, it is necessary that consent/democracy is to be understood in the most minimalist way possible, i.e., as the Schumpeterian formula that lawmakers and the government are selected via a ‘competitive struggle for [the] people’s vote’ (Schumpeter, 1974 [1942], p. 269; Møller and Skaaning, 2013). With a thicker definition – such as liberal democracy (see Møller and Skaaning, 2011) – other aspects of the rule of law would be included in the definition of the concept, meaning that the different dimensions would be conflated by definitional fiat. While the sanctions dimension emphasizes the importance of horizontal accountability, consent instead has to do with the vertical accountability of the electoral channel, i.e., the ability to ‘throw out the rascals’.

The substance of the rules

The first dimension covers the character of rules in themselves, the second and third cover the manner in which these are safeguarded. Why is the addition of a fourth dimension – centred on the substance (or content) of the rules – warranted? The best way to understand this is to hark back to Montesquieu’s (1989 [1748], p. 155) famous definition of liberty: ‘Liberty is the right to do everything the laws permit; and if one citizen could do what they forbid, he would no longer have liberty because the others would likewise have this same power.’

As Tamanaha (2004, p. 37) reports, Benjamon Constant criticized Montesquieu’s formulation, aptly pointing out that such ‘legal liberty’ (formal legality) is worth little if the laws are repressive. Hayek, too, has been severely criticized on this score. To quote from Caldwell’s (2004...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I On Definitions

- Part II On Measures

- Part III On Patterns

- Part IV On Causes

- Conclusions: Taking Stock and Looking Forward

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index