eBook - ePub

Creativity and Humour in Occupy Movements

Intellectual Disobedience in Turkey and Beyond

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Creativity and Humour in Occupy Movements

Intellectual Disobedience in Turkey and Beyond

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume offers scholarly perspectives on the creative and humorous nature of the protests at Gezi Park in Turkey, 2013. The contributors argue that these protests inspired musicians, film-makers, social scientists and other creative individuals, out of a concern for the aesthetics of the protests, rather than seizure of political power.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Creativity and Humour in Occupy Movements by A. Yalcintas, A. Yalcintas, A. Yalcintas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art General1

Intellectual Disobedience in Turkey

Altug Yalcintas

Abstract: Yalcintas argues that the Gezi protests were a spontaneous form of activism in which individuals, dissatisfied with the established ideologies and viewpoints in the Turkish political rhetoric, occupied the squares and streets of major cities in Turkey in the absence of a political party and trade union. The protestors were intellectually disobedient individuals, pulled into politics as intellectual activists with instincts of creativity and senses of humour. The protesteors used untried metaphors to communicate their desires for the future, specifically about the intellectual climate in which they desired to live.

Keywords: creativity; Gezi protests; humour; intellectual disobedience

Yalcintas, Altug. Creativity and Humour in Occupy Movements: Intellectual Disobedience in Turkey and Beyond. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137473639.0005.

June 2013 will be remembered as a date in the social and political history of Turkey when individuals with instincts of creativity and humour shifted the intellectual paradigm in the country towards a collective experience of politics as arts and ingenuity. The Gezi protests inspired musicians, film-makers, novelists, poets, writers, social scientists, and other members of the creative class out of a concern for the aesthetics of the protests, rather than the seizure of political power.1 The ever-growing variety, amount, and quality of artwork, in the forms of documentary, music, photography, poster, banner, slogan, graffiti, stencil, anthem, novel, short story, poem, and theatre play, in addition to the social research on the forms of artwork produced during and after the Gezi protests, suggest that these protests should be studied and interpreted as well an action art as a social event with political consequences. The creative and humorous power of the Gezi protesters has had such a great influence on the intellectual life of the country that individual creative pieces on or about Gezi have become components of action art nationally, which is a native form of performing art produced in the political sphere, and which resembles most closely the Czech Action Art in the former Czechoslovakia where art ‘was a vassal to the political situation and met with peripeteia that the West was unfamiliar with’ (Morganová, 2014, p. 19). During the 1960s, Czechoslovakia took the path to a liberal socialism, or ‘socialism with a human face.’ However, following its occupation by Warsaw Pact troops in 1968, Czechoslovakian artists had to perform under political suppression. Until 1989, artists created an ‘unofficial culture,’ an authentic form of expression of uncensored creativity. Art historian and expert on Czech Action Art, Pavlina Morganová (2014, p. 50), remarks thus:

[Czechoslovakian artists] decided to take art from the safety of the galleries and theaters and lead it out into the streets. Their intention was to have it leave an impression on random passers-by; to surprise this arbitrary witness in the middle of his routine, and thus bring a different level of awareness to it; to do away once and for all with the division between the active artists and the passive viewer; to give everyone the chance to become involved so that they could forget for a while about social customs and biases, so that they could play and enrich their lives. In doing so, the first action artists radically expanded art’s possibilities and tried to give it back to everyday life. It still seemed possible at the time.

The ‘disproportional intelligence’ of the Gezi protesters created complex political artworks in public space, where activists were both producers and consumers of the products of political creativity.2 For instance, a radical and popular activist group during the Gezi protests, called the Anti-capitalist Muslimes, organized ‘suppers on the surface of the earth’ in which random people joined each other on massive banquets stretched throughout İstiklal Street in İstanbul to break fasts during Ramadan as a form of protest. In another instance, during many football games in Istanbul, fans of football clubs, especially the fans of the Fenerbahçe FC, chanted slogans from the Gezi protests, such as ‘Everywhere Taksim, everywhere resistance,’ ‘This is just the beginning, keep up fighting,’ or the anthem of Ali İsmail Korkmaz, on the thirty-fourth minute of the games.3 Likewise, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) individuals organized one of the biggest parades on İstiklal Street, where activists rallied against discrimination and for their rights (see Ayşe Deniz Ünan’s chapter on the interaction between the Gezi protests and the LGBT rights movement in Turkey, this volume.) Individual performances also abounded during the Gezi protests. Davide Martello, pianist and composer, performed live in Taksim Square on 16 June 2013. On 17 June 2013, Erdem Gündüz, known as the ‘standing man,’ stood still for eight hours in Taksim Square after the police evacuated the occupation site, Gezi Park. In the following days, hundreds of people copied his form of protest throughout the country. On 20 June 2013, a bikini-clad woman named Mine Dost protested the government by running and doing stunts in Taksim Square. The Whirling Dervish, who was wearing a gasmask, the Lady in a Black Dress, and the Lady in a Red Dress (Sherlock, 2013; Stone, 2013) also showed how creative forms of non-violent individual action can disperse police brutality during massive demonstrations. Many of the performances during the Gezi protests suggest that protesters were not simply political activists, but also intellectual activists, willing to use their creativity in the political sphere. For instance, Hasan Hüseyin Şehriban Karabulut, standing against a barrier set up by the police, took the initiative as an individual and read a book to police officers in Taksim Square, an action which later turned into a collective action of reading throughout the country. In short, Gezi protesters were able to create an art space for themselves in which both individually and collectively, they expressed political messages in novel ways. Gezi protesters were artists in action, and their protests were, simply, action art.

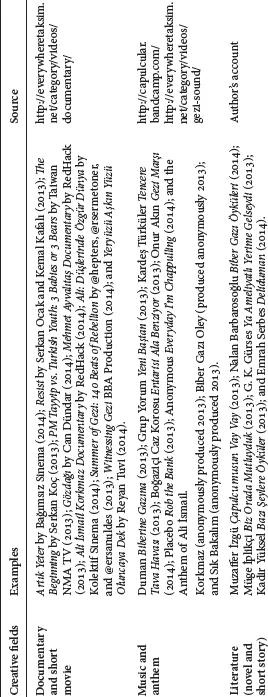

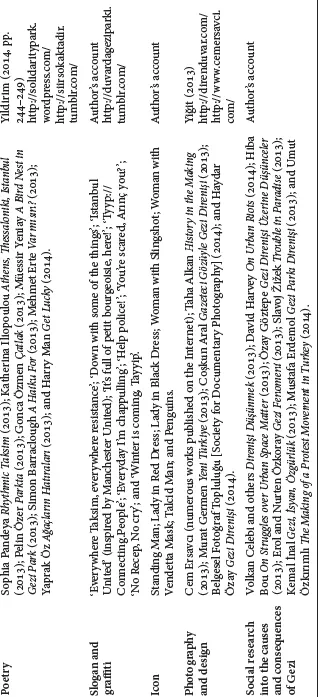

Action art during the Gezi protests took many forms, not just that of performance. The Gezi protests were documented in short movies and documentaries. According to Everywheretaksim.net, a website which archives material on or about the Gezi protests, hundreds of videos were filmed during and after the protests. On the Capulcular.Bandcamp.com archives, as of October 2014, 148 songs by individuals and bands connected to Gezi were freely available for listening and downloading. Emrah Serbes’ novel Deliduman deals directly with the protests, and has been amongst the best-selling novels since it was published in 2014. Perhaps most famously, the Gezi protests appeared in photos and works of design in the international media, such as the cover design of The Economist’s 29 June–5 July 2013 issue.4 During the demonstrations, individuals advanced or took part in the setting up of new media platforms, such as Çapul TV, Kamera Sokak, Ötekilerin Postası, and Eylem Vakti, to communicate news, messages, and images from wherever the action was taking place. Gezi has even had an impact on architecture.5

Gezi has inspired a large number of social researchers as well (Aydemir and Others, 2014; Erdemol, 2013; Göztepe, 2013; İnal, 2013; Özkoray and Özkoray, 2013). The first paper on these events appeared in a peer-reviewed journal (Kuymulu, 2013) during the peak of the protests. Alain Badiou, Jean-Luc Nancy, Immanuel Wallerstein, and Tariq Ali discussed Gezi and offered solidarity with the protesters in Turkey (Ali, 2013; Çelebi and Others, 2013; Wallerstein, 2013), while Noam Chomsky, David Harvey, and Slavoj Žižek were interviewed about the protests (Bou and Moumtaz, 2013; Harvey, 2014; Žižek, 2013). Musicians such as Roger Waters and Joan Baez sent messages about the occupy movement in Turkey (Waters, 2013). Placebo filmed a video on Gezi for their song ‘Rob the Bank’ (2013). During the Istanbul concerts by a number of internationally famous bands, including Massive Attack and Portishead, listeners sang songs for those who lost their lives during and after the protests. Roger Waters paid special attention to the demonstrations by incorporating pictures of five people who died during Gezi into his show, The Wall, in August 2013 in Istanbul. Many natural scientists who were concerned about police brutality, also took action. Twenty-five medical scientists, amongst whom were Nobel Prize winners Robert F. Curl, Paul Greenard, Ronald Hoffman, and Richard R. Schrock, published a letter in Science in July 2013 (Altındiş et al., 2013), arguing that Turkish police forces had to cease the violent response to protesters.

TABLE 1.1 Examples of creative works produced during and after the Gezi protests, June 2013–October 2014

What were the sources of creativity in the Gezi protests? What fed the spirit in Gezi Park that turned the entire country into a creative space? In April 2013, leading up to the Gezi protests, there were demonstrations against the redevelopment plan of the movie theatre Emek, one of the oldest in the Taksim region. Hundreds of people protested against the demolishing of the historical building in which the movie theatre was located. The building was nevertheless torn down to make space for a shopping mall. The government also had expressed its intentions to demolish the Ataturk Cultural Centre in Istanbul, considered one of the iconic buildings of the Republican era and which was equipped with an opera hall and a movie theatre, as part of a reconstruction plan in the same region. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the leader of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), expressed plans to build a mosque instead. The Centre was not demolished, but it has remained deserted and idle since 2008. Also in 2013, Erdoğan stated that the state-owned opera and ballet houses would soon be closed down, arguing that the government should not take part in the performing arts industry. Threatened and bullied on a number of occasions by the AKP government and its police force during the weeks and months preceding the Gezi protests, the artists working in creative fields such as cinema, theatre, and operas found themselves in conflict with the construction industry, which aimed to displace the spaces occupied by the creative class. As Utku Balaban argues in his chapter in the present volume, when Gezi Park was occupied on 27 May, Muammer Güler, the Minister of Interior, cared more for the Kalyon Inc.’s property on the site of protests than for the safety of protesters. The Gezi protests created the opportunity for the creative class to express the public’s discontent with a government increasingly hostile to secular arts.

Several accounts of what ‘really’ happened during the Gezi protests have appeared in a number of publications and online sources. Although I find many of these narratives helpful for a better understanding of the evolution of the protests, I believe that chronologies of the events that took place during the protests would be incomplete without a hypothetical perspective or proposition on the nature of the protests. Without any such perspective, the rearrangement of facts lacks coherency and provide no in-depth insight into the causes and consequences of the demonstrations. Below, I account for the Gezi protests as an emergent social phenomenon. I claim that, in May and June 2013, a political reinforcement mechanism was in operation which enhanced the significance of a few small events (such as uprooting of a ‘bunch of trees’) and led to unexpected social turmoil which had tremendous effects on the political life of Turkey. My intention is to show that the Gezi protests have been a continuous process of transformation in which intellectually disobedient individuals keep the process running with their power of creativity and humour. In the absence of an organizing party or individual to make decisions and give orders to the masses of demonstrators about what they should do, the protesters spontaneously created higher levels of order in which politics has now become impossible without calculating the possible unintended consequences of the absurd and bizarre nature of political rhetoric. That is to say, since the Gezi protests started, the creative class have been more eager to debunk the political, social, and intellectual life in Turkey through the use of irony and humour. The protests may be over; however, the creative and humorous power of the country is now pushing against mainstream politics harder than before in order to reveal the conservative policies of the government in Turkey and throughout the Middle East.

Political reinforcement in May and June 2013

Visible resistance kicked off in Istanbul Gezi Park, the only park in the Taksim area, when the trucks of a construction company, Kalyon Inc., which was closely related to the government, started to rip out ‘a bunch of trees’ on 27 May 2013. The aim of Kalyon was to replace the park with a new shopping mall. Sırrı Süreyya Önder, an MP (Member of Parliament) of the opposition Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), accompanied by a group of environmental activists which totalled just over 50 individuals, came together in the park to stop the project. Activists set up tents and stayed in the park overnight, occupying the site slated for demolition.

On 28 May, at 5 a.m., the police brutally attacked the occupiers, burning the tents in which activists were staying.6 Pictures of this brutality spread quickly...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Prelude: Occupy Turkey

- 1 Intellectual Disobedience in Turkey

- 2 Political Potential of Sarcasm: Cynicism in Civil Resentment

- 3 Vernacular Utopias: Mimetic Performances as Humour in Gezi Park and on Bayndr Street

- 4 Gezi Protests and the LGBT Rights Movement: A Relation in Motion

- 5 Just a Handful of Looters!: A Comparative Analysis of Government Discourses on the Summer Disorders in the United Kingdom and Turkey

- Epilogue: Joy Is the Laughter of the Resistance

- Name Index