eBook - ePub

King Returns to Washington

Explorations of Memory, Rhetoric, and Politics in the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

King Returns to Washington

Explorations of Memory, Rhetoric, and Politics in the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Exploring the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial (King Memorial) in Washington, DC through a multi-faceted rhetorical analysis of the site's visual and textual components, Jefferson Walker reveals multiple critical, popular, privileged, and vernacular interpretations of the site and Dr. Martin Luther King's memory. Walker argues that the King Memorial and its related texts help to universalize and institutionalize King's ethos - creating a contentious rhetorical battleground where various people and organizations contest the "ownership" and use of King's memory. Walker uses these analyses to uncover how the site contributes to the public memory of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access King Returns to Washington by Jefferson Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Abstract: Chapter 1 traces the public memory of King from his death in 1968 to the present day, examining how his memory has been publicly appropriated for various, contrasting causes and how he has ultimately come to be viewed as a “national savior.” The chapter briefly discusses other relevant national memory sites and commemorative occasions, including Atlanta’s King Historic Site and the federally recognized MLK Day, before introducing the King Memorial as the primary space for remembering King at the national level. This chapter’s approach underscores the significance of the memorial, while introducing themes related to King’s memory that come into play throughout the book.

Keywords: civil rights memory; commemorative rhetoric; King Memorial; public memory; Martin Luther King, Jr.

Walker, Jefferson. King Returns to Washington: Explorations of Memory, Rhetoric, and Politics in the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. DOI: 10.1057/9781137589149.0004.

Sitting at their kitchen table in 1983, George Sealey and his wife, Pauline, discussed the lack of memorials in the nation’s capital that were dedicated to African Americans. Washington, DC, then a predominately Black city, boasted few Black memorials and monuments, while the National Mall claimed none. Sealey brought the issue to several of his Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity brothers, who agreed to campaign for the creation of a memorial to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the National Mall.1 As an African American activist never elected to office who preached a philosophy of nonviolence, King would certainly stand out from the presidents and war heroes then honored on the Mall. Yet somehow King’s inclusion seemed natural. By 1983, King had already been memorialized with monuments, buildings, and roads throughout the country and, in November of that year, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill into law making King’s birthday a federal holiday.2 Moreover, while the Mall had long honored national heroes from the past, King was instrumental in giving the space actual historical significance by leading the 1963 March on Washington and delivering his celebrated “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. King belonged on the National Mall.

What began as an idea at a kitchen table turned into a massive twenty-seven-plus-year effort by public servants, Alpha Phi Alpha, the King Estate, and numerous other individuals and organizations that ultimately resulted in the Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial. The Memorial opened in 2011, purporting to be a “public sanctuary where future generations of Americans, regardless of race, religion, gender, ethnicity or sexual orientation, [could] come to honor the life and legacy of Dr. King.”3 Fittingly, the Mall’s first memorial to an African American opened during the term of the nation’s first African American president, Barack Obama. Speaking at the site’s October 16, dedication ceremony, Obama proclaimed, “[T]his is a day that would not be denied. For this day, we celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s return to the National Mall.”4 Obama and other speakers at the event recognized the importance of the memorial as a now-permanent fixture on the National Mall, the country’s “front yard.”

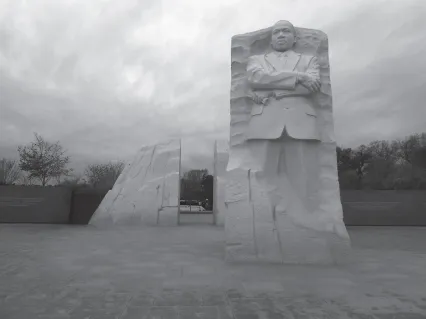

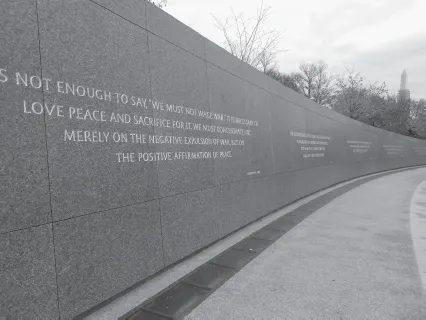

Located at the northwest corner of the National Mall’s Tidal Basin, the Memorial’s design draws inspiration from a quotation from King’s “Dream” speech: “Out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope.”5 The Memorial presents a physical manifestation of this metaphor through its primary design elements: a “Stone of Hope,” a large granite stone inscribed with the image of King, placed in front of the “Mountain of Despair,” two stones that serve as the central entryway into the plaza (Figure 1.1). The “Stone of Hope” features King standing and facing away from the two parts of the “Mountain of Despair,” with arms folded and eyes solemnly gazing across the Tidal Basin toward the Jefferson Memorial. On either side of the Memorial’s main features are polished granite walls inscribed with quotations from several of King’s writings and speeches (Figure 1.2).

Throughout its conception and construction, the Memorial received national attention and praise for its efforts in celebrating King’s memory. However, not all of the Memorial’s attention was positive, as the media reported numerous controversies surrounding its history and design. Some critics railed against the King Memorial for being “made in China,” drawing attention to the statue’s design by renowned Chinese sculptor Lei Yixin, its use of Chinese granite, and the employment of Chinese labor.6 Others, notably including the late author and activist Maya Angelou, criticized the Memorial for paraphrasing a quotation from King in a way to make him sound “arrogant.”7 The site’s dedication ceremony was not without its own controversies, as Obama and other speakers turned the occasion into somewhat of a political forum.8

FIGURE 1.1 The “Stone of Hope” in front of the “Mountain of Despair”

FIGURE 1.2 Inscription wall

As the first memory site of its kind on the National Mall and, especially, as a site simultaneously levied with both praise and criticism, the King Memorial proves itself worthy of scholarly attention. Adding further significance to any project examining King’s memory are the many educators, activists, and members of the media who lament the perceived lack of knowledge of King’s life and accomplishments, especially among younger generations of Americans. For instance, Jasmyne Cannick, an African American community activist and columnist, says of younger generations, “They don’t know what organization he founded, they don’t know key lines of his speeches, they don’t know when he was killed. I’m embarrassed and disappointed by this.”9 When asked about King’s identity, many individuals might produce answers no deeper than that of fourteen-year-old Marcus Brown: “I know he said, ‘I have a dream.’ ”10 The ways that King’s memory is constructed for such individuals remains a potentially relevant topic for historians, rhetoricians, and public memory scholars to address. The memory of King constructed and institutionalized at the national level by the National Parks Service (NPS) makes the King Memorial a singularly important subject.

Moreover, some scholars mourn the depleted mythic construction of King as the transcendent “national savior.”11 As the nation celebrated the first Martin Luther King Jr. Federal Holiday (MLK Day), in 1987, historian and activist Vincent Gordon Harding wrote, “It appears as if the price for the first national holiday honoring a black man is the development of a massive case of national amnesia concerning who that black man really was.”12 Harding added that society placed King into “the relatively safe categories of ‘civil rights leader,’ ‘great orator,’ [and] harmless dreamer of black and white children on the hillside,” while forgetting him as an evolving, embattled, and confrontational figure.13 In King’s case, as the memory of his universal messages of peace and equality have been celebrated, his more specific agendas, messages, and accomplishments have been forgotten.14 By studying the King National Memorial, I am able to examine this trend, of celebrating the general to the detriment of the specific, at the national level.

Another closely related and equally troubling issue to scholars is the mythic narrative of King as the only central figure of the civil rights movement. Historian Keith D. Miller explains,

This often-recited narrative locates the start of the racial struggle in 1955, when Rosa Parks’s arrest in Montgomery launched King onto the national stage. Next, the narrative relates several largely non-King protests. Then, it reaches three peaks: the King-identified demonstrations and jailings in Birmingham in 1963; the King-identified March on Washington later in 1963, capped by his “I Have a Dream,” speech; and the King-identified Selma-to-Montgomery March in 1965. Finally, the narrative proclaims the movement died in Memphis at the exact moment when King fell to an assassin’s bullet in 1968.15

Numerous historians and other scholars have repeatedly challenged this narrative in recent decades, yet the myth persists in popular memory.16

Rhetorical critics have demonstrated the prevalence of this myth through a wealth of civil rights-related memory scholarship. King is the most frequently remembered leader of the civil rights movement and, at times, is its lone representative. He is memorialized at the places of his birth and death, in addition to museums, roads, and buildings scattered across the nation. In his study of Memphis, Tennessee’s National Civil Rights Museum, Bernard Armada explains that memory sites tell us “who/what is central and who/what is peripheral; who/what we must remember and who/what it is okay to forget.”17 Memphis’s museum, located at the Lorraine Motel where King was assassinated, places King at the center of the civil rights narrative by telling the story of his final days. Victoria Gallagher studies the King Center, located at King’s birth site in Atlanta, Georgia, and suggests that the plethora of King-related memorials “attempt to apply K...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Building the Dream: The Making of the King Memorial

- 3 The Rhetorical Form and Force of the King Memorial

- 4 Interpretation, Politicization, and Institutionalization: A Rhetorical Analysis of the King Memorials Dedication Ceremony

- 5 Conclusion

- Index