eBook - ePub

Hometown Transnationalism

Long Distance Villageness among Indian Punjabis and North African Berbers

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hometown Transnationalism

Long Distance Villageness among Indian Punjabis and North African Berbers

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Collective remittances, that is to say development initiatives carried out by immigrant groups for the benefit of their place of origin, have been attracting growing attention from both academics and policy makers. Focusing on hometown organisations, this book analyses the social mechanics that are conducive to collective transnationalism.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Hometown Transnationalism by Thomas Lacroix in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Social Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Methodological and Theoretical Outline

1

Selecting Groups: Moroccan Chleuhs, Algerian Kabyles and Indian Sikhs in Europe

The question of why the propensity to engage in development practices varies from one group to another remains unanswered. The discrepancy is all the more puzzling when one considers groups sharing a roughly similar migration history. This conundrum will serve as a starting point for my investigation of hometown transnationalism. Confronting the beginning and the outcome of the same process for different groups brings about the question of parallelisms and bifurcations. It points to the relevance of engaging in comparative analyses and of studying the migration process as a whole. By this, I refer to the need to adopt a temporal perspective when examining migrants’ behaviours, rather than using history, as is often done, as a mere decorative background. I have chosen to focus on three groups which scholarship has rarely approached together: North African Berbers (Chleuhs and Kabyles) in France and Sikhs in the UK. The chapter presents the rationale for selecting these groups and the methodological options retained to carry out this study. It then provides an overview of this conundrum in order to unravel the theoretical issues guiding this research.

The comparative work: Field investigations and quantitative balancing

Altogether, this book rests on a decade and a half of research on immigrant transnationalism in Europe. Initially, this research was undertaken in a postdoctoral framework with a view to confronting my doctoral research findings on Moroccan Berbers in France with a group that shares a roughly similar migration trajectory, Algerian Kabyles, as well as with a group displaying distinctive features, Sikh Punjabis. The choice of these three groups has been driven by a number of common as well as distinctive features. North African Berbers and Sikh Punjabis originate from three specific areas, which are populated by minority groups. The focus on regional groups is deliberate. A national-level approach turns out to be irrelevant for the study of hometown transnationalism. The three groups are archetypal colonial and postcolonial migration groups. Beyond their parallel history, the groups have little in common. The Punjabi settlement in a predominantly multicultural country (UK), as well as the North African settlement in a country perceived as assimilationist (France), are likely to affect both their relation to the area of departure and their patterns of mobilisation. UK-based Punjabis enjoy a more comfortable socioeconomic position than their Maghrebi counterparts. Expatriate Punjabis are scattered around the world while Kabyles and Chleuhs are mostly concentrated in France. Finally, Sikh and Moroccan transnationalism is notoriously dense and varied while Algerian homeland connections remain mostly confined to the family and individual levels.

Based on Mills’ laws of comparison between similar and dissimilar objects, the study aims to highlight the common aspects, which explain why two very distinct groups (Chleuhs and Punjabis) display a similar pattern of transnational engagement. This parallelism of practices is all the more striking since, as in the Mexican or West African cases, the volume of collective remittances to India and Morocco increased from the 1990s onward. This justifies not only a synchronic comparison of the different groups, but also a look over a long period to see why their evolution converged. Yet, conversely, the intent here is to highlight discrepancies which might explain why Kabyles do not share the same attitude. It has always been a challenge for scientists to explain why something does not occur. In this particular instance, a focus is given to the distinctive parameters that differentiate both groups: the countries of departure and their attitudes towards immigrants. This exercise opens up the possibility of exploring the various dimensions which account for the dynamics of hometown transnationalism: the anthropological foundations of villageness, the remoulding of this villageness in a migration context, the integration effects of transnational engagement, the role of civil societies and the shaping forces of national and international policies. It also offers the possibility of identifying universal dynamics beyond the specific cultural and political forms taken by each case study. For example, the building of palatial houses by migrants is not the product of the caste system and the pursuit of izzat, as sometimes mentioned in the literature on Punjabi migration. Rather, it is a widespread phenomenon observed all around the world and which takes a specific shape in India due to the context of the caste system. In other words, by contrasting context-specific observations, this comparison gives an additional edge to the interpretative work by highlighting the possible existence of common forces. In doing so, the comparison avoids any culturalist interpretation of social phenomena.

The comparison is based on extensive fieldwork carried out in both arrival and sending settings. In total, 131 semi-structured interviews with migrants and stakeholders have been carried out in the Midlands, London, Chandigarh, Amritsar, New Delhi, the Parisian region, Perpignan, Marseilles, Lille, Rabat, Agadir and Tiznit. On-field observations were made in 19 villages, including 14 in Morocco and five in India. For security issues, I could not to go to Kabylia. Contacts were made through key associations, NGO platforms or through associative databases, and networks were followed between Europe and sending areas through snowballing. This approach dwells on the classical aspects of a multi-sited research. On-site visits and interviews provide the possibility not only to unravel the localised effects of decisions taken overseas but also to enter the less tangible domain of people’s conscious and unconscious representations. In particular, field investigations were instrumental to identifying informal activities and relations that leave no statistical traces. This is particularly so, as will be seen, for Sikh volunteering, which often unfolds outside of institutional frameworks.

This approach was balanced by a quantitative exploration of existing databases. I felt the need to use a statistical approach for two reasons: first, while snowballing is a powerful instrument to understand the internal functioning of social chains and their actors, it exposes the researcher to the risk of focusing on what could be but an exception within the migrant population at large. This is all the more true since informants and media sources tend to point researchers towards showcase examples of associations and projects that were particularly successful but weakly representative. A second and related loophole is that a qualitative approach tends to highlight the discourse of leaders. In contrast, the less articulate and less accessible standpoint of the mass of more or less occasional members tends to be neglected. With this in mind, this work draws on the use of two sources of data. The first one is a database of associations I compiled from various sources. In France, any association is to be registered in the Journal Officiel, which is a centralised source of information about formal associations.1 In contradistinction, there is no legal obligation in the UK for an association to be registered and there is a diversity of possible registrations (as a charity, a friendly or provident society, etc.), hence the necessity to multiply the sources of information regarding associations. For this purpose, I used the online register of the Charity Commission,2 the multi-faith directory of religious organisations of the University of Derby,3 the list of development organisations marshalled by the platform of migrant organisations, “Connection for Development”, as well as various local associational listings in the mains areas of immigrant settlement. Based on their websites and on direct contact, I was able to eliminate those who do not include any immigrant. In the end, a compilation of 1,600 Moroccan, 1,200 Algerian and 1,200 Indian associations has been put together, including information about their localisation, type, activities in the country of settlement and overseas, their aims and, when possible, their area of work abroad. Among them, 190 Moroccan, 140 Algerian and 150 Indian HTOs were identified. The second main source of data exploited for this research is the Institut national d’études démographiques (INED) survey Trajectoires et Origines.4 Its primary aim is to measure current immigrant integration trends in France, but it includes an interesting set of questions on transnational activities, including charitable and associational ones. The quantitative analysis of both sources has been helpful to quantify the relative weight of hometown organising and cross-border charitable engagements with regard to broader immigrant volunteering, as well as to identify existing trends over the last two decades.

The migration history of investigated groups

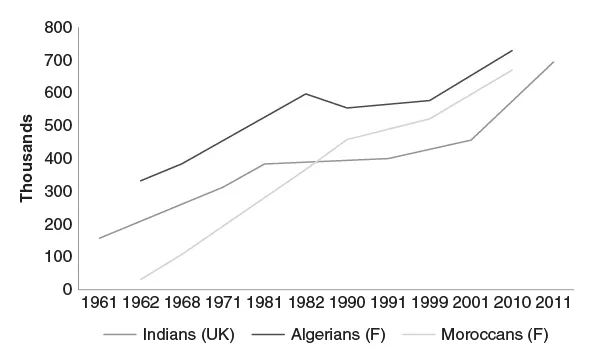

The three investigated groups are all products of colonial history. The contours of contemporary Berber and Sikh political identity are rooted in the colonial management of India and North Africa. The specific place these groups occupied during the colonial rule explains the reason why they formed the first migration cohorts to France and the UK (Figure 1.1).

From the Kabyle myth to labour migration

The Kabyle case is emblematic of the distorting effects of colonial control based on the management of differences. A decade after the start of the colonial campaign in Algeria, a scientific mission headed by Alexis de Tocqueville was convened to study the sociological structures of Algerian tribes (1840–1842). The spearhead of the republican “civil-ising mission”, the mission delivered a series of reports5 that laid the ground for colonial anthropology (Scheele 2009; Silverstein 2004, 48 and ff.). The reports pointed to a number of distinguishing features characterising Kabyle culture:6 qanoun (customary code), axxam (house), tajmaat (patriarchal assembly), tiwizi (collective duties) and recorded an array of Kabyle mythic narratives. The reports also delimited the geographic confines of what was named “Kabylia”, subdivided into the greater and lesser Kabylia separated by the Soummam Valley. This pioneering scientific mission was followed through until independence by a strand of anthropological investigations carried out either by social scientists or by militaries (Germaine Tillion, Robert Montagne, to name but a few). One of the latest studies in that respect was Pierre Bourdieu’s work on Kabyle rural areas (Bourdieu 1977; Bourdieu and Sayad 1964). A department of Berber studies was created at the University of Algiers. After it was closed down by Houari Boumediène in the mid-1960s, some scholars moved to Paris to open the Académie berbère pour les échanges culturels et la recherche (Berber Academy for cultural research and exchanges) (1967) and later the Groupes d’Etudes Berbères (Berber Studies Group) at the University of Paris VIII (1973). This colonial anthropology contributed to forging what is known today as the “Kabyle myth”: a series of cultural traits and representations that trace the boundaries of Kabyle identity (Silverstein 2004, 52). The latter was largely conceived in opposition to “Arab identity”. They are seen as industrious and sedentary mountaineers that have developed agriculture and commerce for their livelihood in contrast with the Arab tribes of the plains that have remained nomadic and live off natural resources. Their Islamisation is presented as late and shallow, while Arabs are seen as fanatically pious. Conversely, any proof of the actual porosity of the putative Kabyle/Arab divide is overlooked, such as the fact that the names of the different elements of the socio-political system (tajmaat, qanoun, tiwizi, arch …) are either Arabic terms or have Arabic roots.

Figure 1.1 Indian, Algerian and Moroccan immigrant populations in France and the UK: 1961–2011

The social and political impacts of this strand of work can be felt even today. The scholarly predicaments of the colonial ideology have been all the more far-reaching as they were established at a time when the French assimilationist model was taking shape. Islam was perceived as an obstacle to assimilation as it is now viewed as a barrier to integration. This set of representations informs a scale of assimilability that still pervades the subconscious of republicanism. The French assimilation model was forged in two crucibles, Algeria and the métropole with two distinct but related objectives: to produce a unified nation out of the cultural mosaic of regional groups and to define a model of incorporation of the colonised “other”. The term “assimilation” was initially coined with regard to a population that somehow concentrated the two forms of inner and outer otherness: the French Jewry (Abdellali 2012, 37). Primary schooling became compulsory in 1833 and later generalised by the two Jules Ferry laws (1881 and 1882) with a view to establishing French as the national language. Jules Ferry was also a fervent advocate of colonial expansion as the vehicle for the dissemination of republican values throughout the world. He established the protectorate in Tunis and sent troops to Africa and Southeast Asia. With school, sport became another privileged locus for nation building (Pierre de Coubertin founded the International Olympic Committee in 1894). In the late nineteenth century (1889), nationality became the legal pillar of the assimilationist model. The need to compensate for the fragile demographic growth as well as the need for conscripts urged authorities to opt in favour of an open jus soli. But there is an Algerian side to the history of this reform. In the late nineteenth century, the majority of the settler population came from Mediterranean countries (Italy and Spain), which posed a potential challenge to the French sovereignty over Algerian soil. The new nationality code allowed for the naturalisation of foreign immigrants. In 1891, the possibility of opening this right to Muslims was fiercely opposed by members of parliament on the ground that it would be conducive to the contamination of French morality by Islamic values (Silverstein 2004, 52). In consequence, French citizenship was closed to indigenous populations unless they renounced their religious personal status. 7

Due to their “semi-assimilability”, Kabyles occupied a specific place in this colonial model. The perceived lesser degree of Islamisation of Kabyles opened up the gates to integration pathways. Sports clubs and schools mushroomed to discipline Berber bodies and minds all over Kabylia, a framework that would be, in postcolonial times, transposed on the French soil to deal with the presence of children of immigrants.8 Their status in the colonial mindset is also one of the factors explaining their migration history. Their French education, but also their image of hard-working people, facilitated their recruitment in the métropole. The first flows of Algerians date back from the late nineteenth century. The region was occupied by French troops in 1857. But it was not until the 1870s that the flows gained momentum. At that time, state authorities, seeking to re-establish the regime’s legitimacy after the defeat against Germany, transferred their effort to colonisation in general and Algeria in particular. The indirect rule that prevailed so far was replaced by direct administrative control. The dismissal of the local elite and the joint increase in taxation were conducive to an important uprising in 1871. Emigration gained momentum when land seizure by colonial authorities – in retaliation to armed protests – led to a massive pauperisation of the Kabyle population. This wave of expropriation disrupted the fragile economic equilibrium in a region characterised by relative overpopulation (247 inhabitants per km2 in the 1930s, 548 in 1970 (Direche-Slimani 1997, 48)) with regard to its land-endowment. The leaders of the movement were sent to New Caledonia. Others found new economic opportunities in France. Prior to the First World War, 4,000 to 5,000 Algerians were living in the métropole, mostly in Marseilles and the collieries of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais. The Kabyle Mountains became the main basin of recruitment of Algerian workforce, due to the impoverishment of the local population but also to the opposition of settlers established in the agricultural plains of Central Algeria to let Arab labourers emigrate. During the First World War, the French army recruited approximately 175,000 soldiers and 78,000 workers in Algeria to offset the heavy losses undergone during the first months of the war (Bouamama 2003, 8). This led to the establishment of a sizeable Algerian community in the country. The need for workforce in the French industry attracted newcomers despite the resistance of settlers and the suspicion fed by the emergence of nationalist movements within the expatriate community.9 After the Second World War, immigration gradually changed. In 1947, the reform of the organic status of Algeria enforced freedom of circulation across the Mediterranean. The Kabyle Mountains ceased to be the sole area providing emigrants and the phenomenon started encroaching on the whole Mediterranean coast, including urban areas. At the eve of the independence war, in 1954, 60% of Algerian immigrants were coming from Kabylia and, in 1966, the date of the first census of independent Algeria, the northeastern provinces (Tizi-Ouzou, Setif and the Aures) are still the origin area of 62% of the emigrant population (Scagnetti 2014, 56). Migration increased during the war, causing the Algerian population in France to nearly double, from 200,000 to 350,000. The violent uprising in Kabylia that followed independence temporarily urged a wave of departures to France. The unrest was a reaction against the Arab–Muslim nation-building project of the new state authorities that left no place for the expression of Berber cultural identity. The movement and the ensuing creation of the party, the “Front des Forces Socialistes” (Socialist Forces Front, FFS), marked the emergence of a Berberist political identity in postcolonial Algeria. Each surge of unrest that affected Kabylia in 1981, 1988 or 2001 generated inflows of migrants to Europe. A century of migration has embedded the region in a dense trans-political and trans-social space linking France and Algeria: a quarter of the families of the area have at least one member abroad (Khellil 1979, 14).

However, after independence in 1962, the Kabyle imprint on the Franco-Algerian migratory field faded. The Algerian state created within the Ministry of Social Affairs the Office National de la Main-d’Oeuvre (ONAMO, national workforce office) to manage the departure flows to Europe. The Evian agreements maintained freedom of circulation for Algerian nationals, generating unexpected outflows of immigrants (25,000 in 1962, 50,000 in 1963) (Scagnetti 2013, 91). But this post-independence surge of migration hides the withdrawal of Kabyle outward movements. Evidence shows that the Berber outmigration gradually decreased from the mid-1960s onwa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I: Methodological and Theoretical Outline

- Part II: Transnationalism: An Emergent Process

- Part III: State Policies and Immigrant Volunteering: The Developmentalist Turn

- Conclusion: Moving beyond the Postmodern Trap of Transnational Studies

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index