![]()

Part I

Researching Innovative Language Teaching

![]()

1

Innovation in Language Teaching: Pedagogical and Technological Dimensions

In order for the reader to understand the present study of technological innovation by teachers of a foreign language in state school settings, and to interpret its implications for other teaching contexts, a certain amount of background knowledge is required. This chapter sets out background information in three areas related to our study, specifically (a) the discipline of language teaching, (b) factors affecting teachers and how they teach, and (c) the integration of technology in educational settings.

This chapter starts with an overview of the teaching methodologies which currently underpin language programmes and curricula in many parts of the world. It briefly situates communicative language teaching (CLT) and task-based language teaching (TBLT) in socio-constructivist educational practice and highlights the challenges and opportunities these methodologies present for language teachers and learners in state school settings. It is important for readers to understand these approaches to language teaching and their differences with more traditional models to appreciate the goals of the project. This discussion will also help teacher and teacher educators situate their own contexts with respect to current language teaching methodologies. Studies of teacher beliefs are also introduced in this chapter, focusing on Bandura’s concept of perceived self-efficacy and Borg’s work in teacher cognition. These frameworks provide the study’s theoretical background in terms of research questions and methods of exploring the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and reflections about their teaching on one hand, and actual observed practice on the other. This is particularly important if the objective is, as in this case, to trace any change occurring over time. The chapter concludes with a discussion of research on technology integration, outlining models of technology adoption in relation to teaching practice and teacher reflection and focusing in particular on IWB-mediated teaching in the language classroom to summarise what recent research has established in preparation for the present study. In this way we set the scene for the study of technological innovation in language teaching, which is the focus of the book.

1.1 Language teaching and learning theory

The project described in this book aimed to support EFL teachers in different school settings in France in using the IWB for communicative and task-based language teaching.1 Before going any further, it is important to define these language teaching methods or approaches and explain the rationale that underpins them so that readers understand the project orientation. This methodological background is also relevant to many other contemporary classroom contexts since this framework informs the design of current language teaching materials and teacher education programmes in many parts of the world. Yet it is not the only influence, as we shall see.

Simply put, communicative language teaching centres on ‘the expression, interpretation and negotiation of meaning’ and seeks to offer learners ‘practice in communication’ (Savignon, 2007). Task-based learning is often viewed as particular case of CLT, focusing on the notion of task, defined as ‘an activity which requires learners to use language, with an emphasis on meaning, to attain an objective’ (Bygate et al., 2001). What is striking in these definitions is the absence of either language-related terms such as grammar and vocabulary, or language skills or competences such as listening and speaking. Instead, the attention is on making meaning.

1.1.1 From grammar-translation to communicative teaching: behaviourist and cognitivist learning theories

CLT and TBLT are therefore quite different from the traditional grammar-translation and structural approaches to language teaching and learning which were common currency in language classrooms for the greater part of the last century. These methods, still used in many places, include features such as

- carefully sequenced presentation of grammatical rules to develop declarative knowledge (ability to recite definitions and rules);

- contrastive analysis (close comparison) of native and second language features (grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation);

- use of translation to verify comprehension and mastery of grammar and vocabulary;

- prioritisation of grammar rules and vocabulary over meaning, often involving techniques such as drilling and memorisation of decontextualised language patterns;

- focus on reading and writing in the target language, including the analysis of literary and other culturally marked texts.

In fact, CLT’s focus on the communicative use of language ‘grew out of a dissatisfaction with earlier methods that were based on the conscious presentation of grammatical forms and structures or lexical items and did not adequately prepare learners for the effective and appropriate use of language in natural communication’ (Celce-Murcia et al., 1997, p. 144). In the latter part of the twentieth century, teachers and researchers were coming to the realisation that the traditional, grammar-based methods did not especially help learners to understand and produce language spontaneously: after many years of classroom exposure, learners were often unable to mobilise the vocabulary they had memorised to communicate effectively, or translate their explicit learning of grammar rules into fluent language production. Conversely, it was observed that ‘natural’ learners, who ‘picked up’ a second language without formal teaching (through extended stay in the target language environment, for example), were often able to use it to high standards of fluency and accuracy without the need, or indeed the ability, to articulate grammar rules explicitly. These observations led to the formulation of a new approach to language teaching focusing not on the structure and vocabulary of the language to be learned, but rather on its use for communication.

The communicative approach can be dated approximately to the 1970s, when concurrent moves in Europe and the US led to the placing of a new construct, ‘communicative competence’ at the centre of innovative teaching methods. This transition from a structural approach to language teaching, relying on the teacher’s presentation of discrete language points in a fixed sequence, to a communicative syllabus, based on the needs and interests of the learner, can also be placed in a wider context of our changing understanding in language education of general learning processes which characterise all human learning.

Early theories of learning, dating back to Pavlov’s early twentieth-century conditioning experiments, are known as behaviourist. In the famous experiment, Pavlov trained dogs to salivate at the sound of a bell by associating this stimulus with another, the presentation of food, producing the automatic salivation reflex. The behaviourist approach views learning in general and language acquisition in particular as habit formation: the teacher provides new language stimuli, learners respond by imitation, and the teacher offers feedback, which reinforces appropriate responses. Behaviourist models of learning characterise the thinking behind a number of the features of grammar-translation teaching methods described above, including the contrastive analysis of native and target languages (to identify new elements to be taught), and drilling or pattern practice, to encourage imitation and avoid errors (or inappropriate new habits).

By the middle of the twentieth century, the cognitive revolution was to replace this behaviourist view of learning with an information processing model. In this view, the learner acquires language by understanding and producing messages, with the teacher providing input to activate subconscious learning mechanisms. In both behaviourist and cognitivist models, learning is viewed as an outcome, or a product – either a set of habits, or a particular competence, corresponding to an abstract, subconscious grasp of the rules underlying the new language. Unlike behaviourists, however, for whom learning is in the gift of the teacher and depends on the environment created for learning, cognitivists situate learning with the learner as an individual.

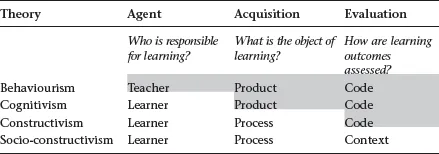

The similarities and differences between these two views of learning are represented in Table 1.1, which lists different learning theories in the first column and identifies differences in terms of the agent in the language classroom (column 2), the perspective on language acquisition as a process or product (column 3), and the assessment of learning outcomes, viewed in terms of mastery of the linguistic code itself, or as an element of performance in a given social context (column 4).

Table 1.1 Teaching and learning with different learning theories

In the lower half of Table 1.1, two particular types of cognitivist learning theory are shown: constructivism and socio-constructivism. The first emphasises the active and individual nature of language learning: like other forms of cognitivism, constructivism situates learning within the individual learner, rather than associating it with the teacher and considering it to be a product of teaching. However, in constructivist classrooms, we are concerned with the process of acquisition, and how learners progress through different stages of competence, rather than the product of acquisition. Unlike other forms of cognitivism, for example, which might judge the language produced by learners in terms of how ‘targetlike’, or close to target language norms it comes, constructivist approaches look at broader questions of the process of language development – the appropriateness of a learner’s participation in interaction, strategies for learning and using language, and progress in expressing and nuancing meaning, for example.

Socio-constructivism goes even further, looking beyond the individual learner’s construction of linguistic knowledge to examine the whole social process of participation in communicative activity (Firth & Wagner, 1997). Here, the teacher fosters collaborative learning as a prerequisite – some might even say a substitute – for individual progress in the second language. Socio-constructivist approaches often downplay language accuracy with respect to target language norms and question the ‘deficit model’ of second language acquisition research. They reject mainstream, cognitivist approaches to research and teaching, which consistently compare learners’ use of language to native speaker norms, which they can by definition never attain. On the contrary, socio-constructivist analyses of learner interactions in a second language focus on the successful co-construction of meaning and communicatively appropriate collaborative action, which can occur despite limited linguistic competence, and indeed constitute evidence of high levels of discourse and strategic competence. There is further discussion of socio-constructivist and social, situated learning in Chapter 2 when we present the methods used to collect data in the present study.

1.1.2 Communicative and task-based language teaching: constructivist and socio-constructivist approaches

This brief and schematic overview of general learning theory allows us to situate communicative approaches to language teaching firmly in the cognitive paradigm. An early advocate of a quite radical form of CLT, Stephen Krashen proposed his Monitor Model (1982), later known as the Input Hypothesis, to provide a theoretical underpinning for a Natural Approach to language teaching (Krashen & Terrell, 1983). This approach takes a Manichaean view of second language teaching, which can be caricatured as ‘meaning good, grammar bad’. This black-and-white version of CLT claims that comprehensible input is a necessary and sufficient condition for language acquisition, and that second languages are best lea...