eBook - ePub

Power and Imbalances in the Global Monetary System

A Comparative Capitalism Perspective

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The author examines the indirect macroeconomic roots of the global financial crisis and Eurozone debt crisis: the escalation of global trade imbalances between the US and China and regional trade imbalances in the Eurozone. He provides new insights into the sources and dynamics of power and instability in the contemporary global monetary system

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Power and Imbalances in the Global Monetary System by M. Vermeiren in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

International Monetary Power: A Comparative Capitalism Perspective

This chapter develops an analytical framework that combines the concepts of the international monetary power literature with those of the comparative capitalism literature. It will be argued that these two strands of literature can complement and reinforce each other, thereby offering new insights that will be elaborated in subsequent chapters. While both were developed in the 1990s and 2000s and share an interest in the issue of national autonomy in the context of financial globalization, there has been a remarkable lack of interaction between both approaches. The international monetary power literature has mostly focused on the international distribution of costs associated with the adjustment of nations to unsustainable balance-of-payments disequilibria – costs that are usually defined in terms of lost macroeconomic autonomy. Scholars working in this field have explained why these costs are typically distributed asymmetrically between nations and why some nations are able to avoid costs and/or deflect them onto weaker nations in the global monetary system. One of their main insights is that the capacity of a nation to avoid the burden of adjustment depends on the extent to which its currency is internationalized. At the same time, however, the literature on international monetary power has neglected the important role of domestic institutions in determining the specific macroeconomic goals nations pursue as well as for understanding the outcome of the international struggle over the distribution of adjustment: it will be maintained in this chapter that the domestic sources and purpose of a nation’s international monetary power are closely linked to the specific institutions of its national model of capitalism.

By exploring these links I will offer new insights that will allow me to challenge and address several shortcomings of the prevailing understandings of the contemporary relations of international monetary power between the United States, the Eurozone and China. The focus on power in determining the outcome of international balance-of-payments conflicts also allows an examination of the interaction of different national models of capitalism in the global monetary system. Scholars of comparative capitalism have only very recently begun to explore how domestic institutions of divergent national models of capitalism have underpinned diverse national growth regimes that can be associated with distinct balance-of-payments dynamics (Hancké 2013; Kalinowski 2013). While being interested in the autonomy of nations to pursue institutionally embedded growth strategies, these scholars have neglected how these nations’ particular insertion in the global monetary system can result in specific balance-of-payments dynamics that either reinforce or disrupt these growth strategies. In other words, just as scholars of international monetary power should pay more attention to domestic institutional variables that shape the sources and purposes of the autonomy a nation pursues in the context of balance-of-payments disequilibria, scholars of comparative capitalism should pay more attention to the way these external imbalances can affect its capacity to adopt a particular growth strategy that is consistent with the domestic institutional logic of its model of capitalism.

This chapter is divided into two main sections. In the first I give an overview of the concepts and insights of the international monetary power literature as well as of the literature’s prevailing understandings of the international monetary power of the United States, the Eurozone countries and China. In the second I discuss the different models of capitalism and growth regimes in these three jurisdictions and discuss how a comparative capitalism perspective can challenge these prevailing understandings.

The political economy of international monetary power

International monetary power: Concepts and definitions

The issue on power in international monetary relations – which can be defined as “a relational property that exists when one state’s behavior changes because of its monetary relationship with another states” (Andrews 2006b: 11) – has received growing scholarly attention in IPE over the past three decades. Given that the balance of payments is the ultimate accounting record of a nation’s monetary relationship with the rest of the world, the consensus view – bundled in a volume by Andrews (2006a) – is that the issue of macroeconomic adjustment to balance-of-payments disequilibria is central to any discussion of its international monetary power (for preceding analyses of international monetary power and the problem of adjustment, see Bergsten 1996: 12–45; Kaelberer 2001; Kirshner 1995). As discussed in the introductory chapter, the costs of adjustment to balance-of-payments imbalances are usually distributed asymmetrically across countries and across different groups within countries. In any balance-of-payments conflict – that is, a situation in which among a group of nations unsustainable imbalances have emerged that require macroeconomic adjustment – the question arises how the “burden of adjustment” will be distributed. The key function of international monetary power is to avoid the burden of adjustment as much as possible. Excessive imbalances automatically generate mutual pressures to adjust, representing an intrinsic threat to a nation’s macroeconomic autonomy: because adjustment can be costly in both economic and political terms, no government likes to compromise its key domestic macroeconomic objectives for the sake of restoring the external balance. As such, the main foundation of a nation’s international monetary power is its capacity to avoid the burden of adjustment to payments imbalances in order to realize its key domestic macroeconomic goals.

As Cohen (2006) has pointed out in a seminal contribution, there are two dimensions of international monetary power that should be distinguished for analytical purposes. First, a nation’s “power to delay” refers to its capacity to postpone the “continuing cost of adjustment”. Taking into account that macroeconomic adjustment is “a marginal reallocation of productive resources and exchanges of goods and services under the influence of changes in relative prices, incomes, and exchange rates” (Cohen 2006: 37), the continuing cost of adjustment is the cost that prevails after this reallocation has occurred. This cost can be above all burdensome for deficit states, “because by definition deficit states absorb resources in excess of their income, and a return to balance means that this state of affair has ceased” (Andrews 2006b: 13). The power to delay is therefore especially important for a deficit country, which has “lived beyond its means” and has “every incentive to put off the process of adjustment for as long as possible” (Cohen 2006: 42). However, surplus countries may have an incentive to delay the process of adjustment as well – for instance, because they fear that they will be compelled to bear the bulk of the burden of adjustment once the process begins, mostly through higher domestic inflation eroding their external competitiveness. A nation’s power to delay follows from its international liquidity position, which is determined by its foreign exchange reserves and/or capacity to borrow from international financial markets: “the more liquidity a country has at its disposal, the longer it can postpone adjustment of its balance-of-payment” (Andrews 2006b: 13). Since “it is almost always easier to absorb surpluses than to finance deficits”, this explains why surplus countries generally have a stronger capacity to delay adjustment than deficit countries (Cohen 2006: 42; Kaelberer 2001).

Second, a nation’s “power to deflect” refers to its capacity to divert the “transitional cost of adjustment” onto other countries. Whenever balance-of-payments adjustment between deficit and surplus countries occurs, distributional implications will arise: adjustment can be accomplished through either a market-driven fall of exchange rates, prices and incomes in deficit countries, reinforced by restrictive monetary and fiscal policies, or a market-driven rise of exchange rates, prices and incomes in surplus countries, reinforced by more expansionary monetary and fiscal policies. The greater the changes in exchange rates, prices and incomes required to restore balance, the greater the transitional costs of adjustment. A nation’s power to deflect refers to its capacity to force other countries to accept the changes in exchange rates, prices and incomes that are necessary to rebalance – a capacity that derives from the fundamental structural variables of its national economy: openness and adaptability. Openness determines its sensitivity to external adjustment: “[t]he more open an economy, the greater is the range of sectors whose earning capacity and balance sheets will be directly impacted by adjustment once the process begins . . . [O]penness makes it difficult for an economy to avert at least some significant impact on prices and income at home” (Cohen 2006: 47). Its adaptability is determined by the “allocative flexibility” of its economy, that is, the flexibility at which diverse sectors are able to reverse an external imbalance without large and/or prolonged price and income changes. Power to deflect is highly significant, since “it tends to impart a hierarchal structure to international monetary relations, with a highly asymmetric distribution of the transitional costs of adjustment. These asymmetries reflect variation in the sensitivity and vulnerability of different states to the shared phenomenon of a mutual payments imbalance” (Andrews 2009: 7).

Cohen distinguishes the “power to delay” and the “power to deflect” as the internal and external dimension of a nation’s international monetary power that refer to its “autonomy” and “influence” in international monetary affairs. The power to delay needs to be understood as “power-as-autonomy”: a nation’s capacity to delay adjustment by being able to finance external imbalances supports its autonomy to continue its macroeconomic policies. The power to deflect, on the other hand, needs to be understood as “power-as-influence”: a nation’s capacity to divert the burden of adjustment to another nation reflects an ability to shape the outcome of a balance-of-payments conflict. While both dimensions of international monetary power are unavoidably related, Cohen (2006: 32–33) argues that they are not of equal importance:

Logically, power begins with autonomy, the internal dimension. Influence, the external dimension, is best thought of as functionally derivative – inconceivable in practical terms without first attaining a relatively high degree of policy independence at home . . . First and foremost, policymakers must be free (or at least relatively free) to pursue national objectives in the specific issue area or relationship without outside constraint, to avoid compromises or sacrifices to accommodate the interests of others. Autonomy, the internal dimension, may not be sufficient to ensure a degree of foreign influence. But it is manifestly necessary – the essential precondition of influence.

Therefore, the argument is that a nation must be first and foremost free to pursue its domestic macroeconomic goals without external constraint – by being able to delay adjustment – before it can be in a position to enforce compliance elsewhere by forcing other nations to do the adjustment. Nevertheless, it should be noted that without the power to deflect the burden of adjustment in a context of unsustainable imbalances a nation can never entirely safeguard its macroeconomic autonomy. As such, the ultimate foundation of a nation’s international monetary power – both of its power to delay and its power to deflect the burden of adjustment – is the capacity to maintain its macroeconomic autonomy.

One of the central tenets of the literature on international monetary power is that this capacity does not need to be exercised intentionally. As Andrews (2006a: 17) notes, “power can exist even absent purposeful efforts to exploit it”. A distinction needs to be made between power as a relational property – the power to act and to avoid being acted upon – and the deliberate exploitation of such a relationship. This is an important distinction for this book, which focuses more on the non-intentional expressions of international monetary power than on intentional strategies of “monetary statecraft”. The unilateral macroeconomic policies of a government and central bank can produce international spillovers that alter the behavior of foreign governments and central banks – whether these spillovers are intended or not. The recognition of non-intentional forms of power is inspired by the work of Strange (1987; 2004) and her distinction between “relational power” and “structural power”. Moving away from the mainstream IPE focus on relational power – direct and more observable forms of power that refer to “the power of A to get B to do something it would not otherwise do” – Strange drew attention toward the existence of structural power, which is exercised indirectly by shaping preferences, influencing the conditions under which other actors operate and changing the range of options open to them, “without apparently putting pressure directly on them to take one decision or to make one choice rather than others” (1988: 31). This form of power will particularly be an attribute of a large and dominant nation, which will be able to influence international outcomes unintentionally “through its unilateral policies or even by the way it has organized the global political economy” (Helleiner 2006: 75).

The importance of non-intentional articulations of international monetary power ensues from the presence of “asymmetric interdependencies” in the global monetary system (Nye and Keohane 1977). These asymmetric interdependencies have two dimensions: (1) asymmetric sensitivities – the fact that the macroeconomic conditions in some nations are more affected positively or negatively by conditions in other nations than vice versa; and (2) asymmetric vulnerabilities – the fact that some nations are more capable of overriding the effects of foreign macroeconomic conditions than others (Cohen 2006). A key insight of the international monetary power literature is that such asymmetric interdependencies are to a great extent based on the global monetary system’s currency asymmetries, whereby some currencies are more extensively used for international financial transactions than others: nations issuing such “key currencies” (KC) generate asymmetric macroeconomic policy spillovers, significantly affecting other nations at the same time as having asymmetric capacity to mitigate monetary shocks emanating from other nations. KC-issuing countries are therefore bestowed with the asymmetrical capacity to avoid the burden of adjustment by – both intentionally and unintentionally – influencing international monetary conditions and shaping the macroeconomic incentives of foreign actors in ways that support their autonomy to advance their macroeconomic interests. Given that the dollar continues to be the “top currency” in the global monetary system, particularly the United States is widely recognized to enjoy such structural monetary power (Strange 1987; Helleiner 2006; Kaelberer 2005; Vermeiren 2010). The fact that US structural monetary power is intrinsically linked to the dominance of the dollar underlines the need to explore the linkages between international monetary power and currency internationalization.

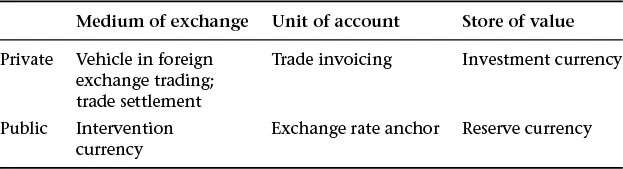

International monetary power and currency internationalization

The fact that a nation’s international monetary power is intrinsically linked to the extent of cross-border usage of its currency is a well-established premise in the literature (Andrews 2006a; Chey 2012; Eichengreen 2011; Kaelberer 2005; Kirshner 1995). The highly uneven international distribution of monetary power mostly derives from the highly hierarchical structure of the global monetary system in terms of currency internationalization. Cohen (1998) characterized this hierarchical structure as a “currency pyramid” – “narrow at the top, where a few popular currencies circulate; increasingly broad below, reflecting varying degrees of competitive inferiority” (1998: 114). What are international currencies and why have some currencies gained a much more prominent role than others? In a recent study that examines the hierarchical structure of the international currency system, Cohen and Benney (2014) differentiate between the “scope” and “domain” of international currency usage. The “scope” of an international currency refers to the range of roles that this currency may play in the global economy; following Kenen (1983), international currencies can be divided along six distinct roles – depending on the three functions of money (medium of exchange, unit of account, store of value) and on whether the currency is used by either private or public actors (Table 1.1). The more a currency is used in these six respective roles, the more it is internationalized. The “domain” of an international currency, on the other hand, refers to geographical scale of use: the more a currency is used in different regions of the world, the more it can be called “internationalized”.

Table 1.1 Roles of international money

Along both dimensions of currency internationalization, the US dollar definitely remains the “top currency” in the world economy.1 The reserve currency role of the dollar has undeniably received the most attention in the literature: the global reserve system remains largely US-centered, with the dollar comprising on average approximately two-thirds of central banks’ foreign exchange reserves over the past two decades – compared to an about 25 percent share of the euro.2 The dominance of the dollar in the global reserve system is intrinsically related to its primacy in the other international currency roles. For those nations that prefer to formally or informally peg their currency, the dollar remains the most-favored exchange rate anchor: the US currency maintained a leading role as exchange rate anchor over the past three decades, with a trade-weighted share of around 50 percent on average – compared to about 7.5 percent of the euro (Bracke and Bunda 2011). The dollar also remains the most-desired currency for the invoicing and settlement of international trade – not only for trade transactions to and from the United States but in many cases in non-US transactions in the rest of the world as well (Tille and Goldberg 2009). Evidently, the role of the dollar as the invoice currency for commodities such as oil is a key pillar of dollar dominance (Momani 2008). In most international currency roles the euro remains a distant second to the dollar and its currency domain appears mostly limited to the European extended region. For this reason, the euro might be called a “patrician currency”; that is, a currency “whose use for various cross-border purposes, while substantial, is something less than dominant and/or whose popularity, while widespread, is something less than universal” (Cohen 1998: 116). The authoritative domain of the renminbi, on the other hand, is essentially restricted to the domestic market, as a result of which the Chinese currency can be coined as a “plebeian currency” (Cohen 1998: 117).

Why has the dollar maintained its position as the top currency in the global monetary system? While there are several other determinants of international currency status (see Helleiner 2008 for an overview), the exceptional innovating capacity, depth and liquidity of US financial markets are arguably the most important source of the dominance of the dollar. The centrality of the US financial system in the world economy and its unique capacity to spawn highly innovative, deep and liquid markets for debt securities have been a crucial source of US monetary hegemony (Konings 2008; Seabrooke 2001; Walter 2006). Particularly, the extraordinarily liquid market for US treasuries has supported the international status of the dollar and the resulting international monetary power of the United States. As Panitch and Gindin (2005) note, “The way American banks had spread their financial innovations internationally in the 1960s and 1970s, especially through the development of secondary markets in dollar-denominated securities, allowed the American state – unlike other states – to substitute the sale of Treasury bills for a domestic pool of foreign exchange reserves and run its economy without large reserves.” The international status of the dollar was significantly strengthened through the indirect institutional power of the United States in international finance. After liberalizing its remaining capital controls and deregulating its financial system from 1974 onwards, the United States was able to consolidate and strengthen the position of the dollar precisely because it was backed by the world’s most advanced financial markets – even after the demise of the Bretton Woods regime and the assumed decline of US economic hegemony (Helleiner 1994). The central function of the US financial system in consolidating the international status of the dollar was also recently highlighted by Oatley et al.’s (2013) complex network approach, which points to the presence of positive feedback loops generated by network externalities in the secondary markets for US debt securities:

Secondary markets for financial instruments are attractive when one can quickly liquidate one position and acquire another. In order to move quickly from one position to another one needs to find agents that will offer the desired trades at a reasonable price. The likelihood of finding willing trading partners rises in line with the number of participants in the market. The more agents that are active...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Introduction

- 1. International Monetary Power: A Comparative Capitalism Perspective

- 2. The Global Imbalances and the Instability of US Monetary Hegemony

- 3. Rising Imbalances and Diverging Monetary Power in the Eurozone

- 4. Reserve Accumulation and the Entrapment of Chinese Monetary Power

- 5. Global Macroeconomic Adjustment and International Monetary Power

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index