This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Financial Crisis and Federal Reserve Policy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Financial Crisis and Federal Reserve Policy is fully revised and updated with the most accurate and thorough coverage available of the causes and consequences of the 2008 Financial Crisis and the role the Federal Reserve played in the recovery efforts.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Financial Crisis and Federal Reserve Policy by L. Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Financial Crises: An Overview

I. Introduction

In 2008, problems that originated in the U.S. subprime mortgage market set off a world-wide financial crisis of a magnitude not witnessed in 75 years. In the United States, this calamity ended up throwing millions of people out of work, wiping out trillions of dollars of household wealth, causing countless families to lose their homes, and bankrupting thousands of business firms, including more than 250 banks. The financial crisis led directly to fiscal crises in nearly every state in the union and drove the federal budget deficit into territory previously experienced only in the exigent circumstances of all-out war. Financial crises can be devastating, and this one ranks among the most damaging in its ramifications because, unlike the Latin American and Russian crises of the 1980s and 1990s, it originated in the world’s most important financial center.

The crisis was not unique to the United States; it touched almost every nation in the world. In part, this pervasiveness was due to the fact that the same fundamental forces that caused the U.S. crisis were experienced in numerous other nations as well. For another part, crises of this severity and source tend strongly to be contagious. Like the influenza pandemic that began at Fort Riley, Kansas in 1918 and spread in two years to kill more than 600,000 Americans and an estimated 30 million people around the world, a major financial crisis spirals outward from its source to ultimately impact countless people in far-flung portions of the globe. The effects of the crisis in the United States spilled over to infect countries from Iceland to Spain to the Philippines.

A financial crisis occurs when a speculation-driven economic boom is followed by an inevitable bust. A financial crisis may be defined as a major disruption in financial markets, institutions, and economic activity, typically preceded by a rapid expansion of private and public sector debt or money growth, and characterized by sharp declines in prices of real estate, shares of stock and, in many cases, the value of domestic currencies relative to foreign currencies. Ironically, the same aspects of capitalism that provide the vitality that makes it superior to other economic systems in fostering high and rising living standards—the propensity to innovate and willingness to take risk—also make it vulnerable to bubbles that eventually burst with devastating results.

The recent worldwide financial crisis, hereafter dubbed the “Great Crisis,” was just one of hundreds of financial crises that have occurred around the world over the past few hundred years. Financial crises date back many centuries to the earliest formation of financial markets. In fact, these crises can be traced back thousands of years to the introduction of money in the form of metallic coins in ancient civilizations. In those times, monarchs often clipped the metallic coins of the realm to forge additional money with which to finance military adventures and other expenditures. Such a debasement of currency often led to severe inflation.

Financial crises come in several varieties; the characteristics, causes, and consequences of each type are sketched in this chapter. Chapter 2 focuses on the particular type—the banking crisis—that characterizes the recent Great Crisis and provides a theoretical framework that enables us to understand the forces triggering banking crises and why such crises occur with considerable regularity.

II. Types of Financial Crises

There are four main types of financial crises: sovereign debt defaults, that is, government defaults on debt—foreign, domestic, or both; hyperinflation; exchange rate or currency crises; and banking crises. In recent decades, sovereign defaults and hyperinflation have been experienced predominantly by impoverished and emerging market economies. While most highly developed industrial nations have avoided sovereign defaults and hyperinflation in the past century, exchange rate crises and banking crises have proven much more intractable. In fact, given the nature of human behavior, these types of crises appear unlikely to someday become extinct. Few economists below the age of 60 believe they have witnessed the last major financial crisis of their lifetime. The recent worldwide financial crisis that was initiated by the U.S. subprime mortgage meltdown—the Great Crisis—is classified as a banking crisis, albeit one in which “banking” is broadly defined to include the “shadow banking system,” comprising hedge funds, investment banks, money market funds, and other nonbank institutions that engage in financial intermediation.

Sovereign Defaults

In a sovereign default, a national government simply reneges on its debt. It fails to make interest and/or principal payments when payments are due. While banking crises have occurred in all countries, sovereign debt defaults in modern times have been rare in highly developed nations. Nevertheless, only a handful of nations—the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and very few others—can claim to have avoided this type of crisis throughout their entire history. Most highly developed nations today (Germany, Japan, U.K.) have resorted to sovereign debt default at some point. Over the centuries the experience of France, Spain, Russia, Turkey, Greece, and numerous other nations has been one of serial sovereign defaults. Governments of Spain, for example, have defaulted more than a dozen times over the course of the nation’s history. And numerous European nations today are struggling to avoid default.

A nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) is the total value of all final goods and services produced in the nation in a given year. The worldwide economic contraction of 2008–2010 was the first instance since the Great Depression of the early 1930s in which world GDP—the aggregate GDP of all nations—declined. The fiscal ramifications of this episode, henceforth referred to as the Great Recession, exposed the debt problems of numerous euro-currency nations. In many nations, 2007 marked the end of an economic boom, often fueled by bubbles in credit and house prices. When the bubbles burst, severe recessions occurred in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. This triggered automatic increases in budget deficits as tax revenues plunged and expenditures increased. When a nation’s annual budget deficit/GDP ratio exceeds the growth rate of its GDP, its debt/GDP ratio increases. If this ratio reaches a critical threshold, investors begin to anticipate the possibility of default and therefore demand a premium in the form of a higher yield to induce them to buy the bonds (lend to the country). A vicious cycle of rising debt/GDP, higher bond yields and thus larger interest expenditures to service the debt, larger budget deficits, and even higher debt/GDP ratios may become established. Ultimately, this process may leave a nation no option other than defaulting on its debt.

The European sovereign debt crisis emerged in early 2010, and is examined in depth in Chapter 8. The “doom loop” or “death spiral” described above appeared first in Greece—traditionally the most profligate European nation. The debt problem became contagious, spreading from Greece to Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Italy fairly quickly, then to Cyprus in March 2013.1 The so-called troika of European bailout authorities—the European Central Bank (ECB), International Monetary Fund (IMF), and European Commission, took actions in 2012 and 2013 to cut short the impending doom loop just described. A key July 2012 announcement by ECB chairman Mario Draghi that the ECB would “do whatever it takes” to contain the crisis helped reverse the spiking bond yields in several European countries and served to calm the waters, at least for awhile.

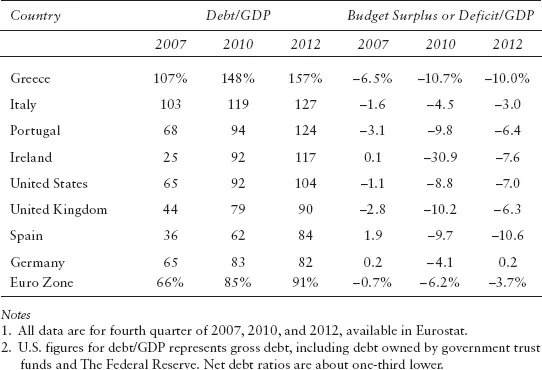

Table 1.1 indicates the explosion of budget deficits and the surge in debt/GDP ratios that occurred in a sample of nations as the Great Recession severely impacted the fiscal condition of governments in Europe and the United States.

In the right-hand portion of the table budget deficits are denoted with a minus sign. The table shows that the overall deficit/GDP ratio in the 17-nation euro zone surged from less than 1 percent in 2007 to more than 6 percent in 2010, before declining to 3.7 percent in 2012. Coupled with negative GDP growth in many countries in this interval, this boosted the debt/GDP ratio of the bloc of nations from 66 percent in 2007 to 91 percent in 2012. The Irish government budget deficit exploded to 30 percent of GDP in 2010 as the government moved to take over the huge debts of its failing banks to prevent their collapse. Note that this boosted the Irish debt/GDP ratio from 25 percent to 117 percent in only 5 years!

Table 1-1 Government Budget Deficits and Debt as Percentage of GDP

Because of the Great Recession, the deficit/GDP ratio increased in every nation represented in the table from 2007 to 2010. This ratio rose to more than 9 percent in Greece, Portugal, Ireland, the UK, and Spain in the fourth quarter of 2010, and to nearly 9 percent in the United States. These massive budget deficits boosted the debt/GDP ratio in all nations shown in the table. By the end of 2010, the ratio exceeded 90 percent in Greece, Italy, Portugal, Ireland, and the United States. With the exception of Germany, these debt/GDP ratios moved even higher by the end of 2012 in all nations represented in the table. This occurred because, while the budget deficit/GDP ratio declined relative to 2010 levels in most nations as severe austerity measures were implemented, this critical ratio remained larger than the growth rate of GDP. In large part because of the austerity measures, numerous European nations endured a second recession in 2012 and 2013.

The European sovereign debt crisis is likely to simmer for years. It is not clear at the time of this writing (summer 2013) whether the 17-nation euro-currency bloc will survive in it current makeup. The fiscal condition of governments in at least 6 of the 17 euro-zone nations remains significantly impaired, and the possibility of sovereign debt default is alive in Europe today.

Hyperinflation

A second type of financial crisis, hyperinflation, is essentially a de facto default on debt—a more subtle form of default than overt default. With hyperinflation, governments and other debtors pay interest and repay the principal on their debts with units of currency that are worth dramatically less than their values at the times the debts were incurred.2 Less developed countries and emerging nations are much more prone to hyperinflation than are modern industrial nations.

Nevertheless, if we (arbitrarily) define hyperinflation as inflation at rates in excess of 100 percent per year, few nations can claim they have never experienced hyperinflation. Germany experienced such extreme inflation in the early 1920s that billions of marks were needed in 1923 to purchase a good or service that a single mark had purchased ten years earlier. Poland and Russia also experienced episodes of inflation at rates in excess of 10,000 percent per year in the early 1920s, as did Hungary, Greece, and China in the mid-1940s. In the 1980s and 1990s, such Latin American nations as Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru were plagued by bouts of inflation at rates in excess of 1,000 percent per year. And even the United States had one experience with hyperinflation—a brief period of inflation with annual rates in excess of 150 percent in 1779, during the Revolutionary War.3

Hyperinflation typically occurs in a nation with an unstable and often corrupt government, a poorly developed financial system, and a rudimentary or virtually nonexistent tax system. Without a satisfactory tax system, a government must borrow to finance itself—it is forced to deficit spend. But given the absence of developed bond markets, along with a dearth of savings among the populace in poor countries and a widespread distrust of government in such nations, governments typically finance deficits through the exploitation of subservient central banks. The government borrows directly from the central bank or simply prints large quantities of the currency to finance expenditures. Therefore, the money placed in the private sector as the government spends is not recouped, either through tax receipts or through sales of bonds to private sector entities. The quantity of money increases as the government makes payments for goods, services, and salaries of government employees.

Rapid expansion of the money supply typically leads to rapid increases in expenditures, driving up prices of goods and services. After a period of high and rising inflation, hyperinflation sets in. To see how this happens, consider that inflation essentially imposes a tax on money (checking accounts and currency), the tax rate being the rate of inflation. Money depreciates in real value each year at a rate equal to the rate of inflation. As inflation rises, the tax rate increases and people respond by reducing demand for money—that is, they are less willing to hold wealth in the form of money. After reaching a critical threshold, rising inflation expectations begin to cause people to spend money more quickly to beat the anticipated price hikes. They rid themselves of it more rapidly to purchase goods and services and real assets. The velocity of money increases, and prices begin increasing even more rapidly than the nation’s money supply. Once this mechanism sets in, it is extremely difficult to eradicate inflation. In many instances, hyperinflation is followed by a collapse of the monetary economy, as the unwillingness of people to accept money as payment means that the process of exchange reverts to a system of barter. The extreme inefficiency inherent in a barter economy means that depression is almost inevitable.

Exchange Rate Crises

A third type of financial crisis is an exchange rate crisis or currency crisis. Emerging economies—those not as rich as the United States and other highly industrialized nations but not as poor as most African countries—seem especially susceptible to exchange rate crises. In the past 20 years, currency crises have occurred in such countries as Mexico in 1994; Thailand, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, the Philippines and South Korea in 1997 and 1998; Russia in 1998; and Argentina and Turkey in 2001. In addition to causing asset price declines and severe problems in the banking sector, exchange rate crises are characterized by large-scale capital flight as funds are withdrawn and placed in countries that exhibit more favorable economic prospects. The outflow of financial capital triggers exchange rate depreciation, higher inflation, rising interest rates, falling asset prices, and increasing bank failures.

Exchange rate crises are typically preceded by a period of large and sustained inflows of financial capital from other nations. These capital inflows often arise in response to the liberalization of markets, in which competition is promoted through dismantling of government controls, privatization of government-owned industries, and removal of impediments to international trade in goods and services. Such reforms often lead to perceptions that the economic outlook and rates of return on assets in the nation are likely to be superior in the foreseeable future. Agents in foreign nations invest in countries in which expected returns are highest, and economic liberalization of a previously repressed economy tends to create such opportunities. Following a series of annual capital inflows, a nation has accumulated large debts to foreign nations, typically amounting to a significant percentage of its GDP. The nation that is the recipient of these capital inflows thus becomes vulnerable to unexpected shocks. A shock eventually occurs that reverses the inflow of capital, leading to a depreciation of the nation’s currency.

Mexico’s currency crisis of the early 1990s provides a clear example. Following a major debt crisis in 1982, a consensus was reached in Mexico in the mid-1980s that prosperity and growth could be best achieved through a policy of market liberalization. State enterprises were privatized, tariffs were reduced, and import restrictions were lifted.

A regime headed by Carlos Salinas and staffed by Ph.D. economists trained at American Ivy League universities ascended to power in 1988. Shortly thereafter, the Brady Plan of 1989 called for forgiveness of much of the foreign debt accumulated by Mexico in the previous decade. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), originally negotiated between the United States and Canada, was extended to include Mexico. Prospects for future Mexican exports to the United States and Canada brightened. It appeared that Salinas’s free trade initiatives and market liberalization would bring permanent benefits to Mexico. Taken in tandem, the extension to Mexico of the NAFTA treaty, the Brady Plan for debt forgiveness, and the market liberalization program of the Salinas regime produced a major change in the outlook for prosperity in Mexico. Foreign capital began flowing into the country, including more than $30 billion in 1993 alone.

In the case of Mexico, early hints of an impending crisis began to appear as the emergence of large budget deficits and rapidly increasing government debt began to make foreign holders of government bonds wary of possible sovereign default on this debt. Anticipation of economic repercussions associated with an impending government default rendered privately issued debt also unacceptably risky to foreign investors. For Mexico, the tipping point came with the March 1994 assassination of the charismatic presidential candidate Donaldo Colosio, heir apparent to Salinas, together with a rebellion in the poverty-stricken state of Chiapas. These events dashed hopes of sustained political stability and contributed to the capital flight.

In such situations, the government typically does not have sufficient reserves of foreign currencies to prevent currency depreciation. In many instances, emerging nations fix their exchange rate to the U.S. dollar to hold down inflation and contribute to stability. Especially in a fixed exchange rate regime, strong signals of impending problems in an emerging nation lead to a one-sided speculative attack on the currency because it is clear to speculators that the domestic currency will either be devalued or the exchange ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Financial Crises: An Overview

- 2 The Nature of Banking Crises

- 3 The Panic of 1907 and the Savings and Loan Crisis

- 4 Development of the Housing and Credit Bubbles

- 5 Bursting of the Twin Bubbles

- 6 The Great Crisis and Great Recession of 2007–2009

- 7 Aftermath of the Great Recession: The Anemic Recovery

- 8 The European Sovereign Debt Crisis

- 9 The Framework of Federal Reserve Monetary Control

- 10 Federal Reserve Policy in the Great Depression

- 11 The Federal Reserve’s Response to the Great Crisis: 2007–2009

- 12 Unconventional Monetary Policy Initiatives: 2008–2013

- 13 The Federal Reserve’s Exit Strategy and the Threat of Inflation

- 14 The Need for Regulatory Reform

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index