![]()

Part I

FROM BROKEN INVESTMENT MODELS TO SUSTAINABLE STRATEGIC INVESTING

![]()

Chapter 1

PERILS OF THE MISGUIDED INVESTOR: LESSONS FROM A CFO – PART 1

Martin Heller began his career as a certified public accountant in the late 1970s. A highly qualified young man, he spoke several languages and soon established himself as a successful professional in the financial services industry. He married, had three children, bought a roomy family home, and as his income grew he was able to pay off his mortgage and save a fair amount.

In 1990, with a small inheritance along with his savings, Martin began to search for a way to invest his money. Lacking investment expertise, he sought advice from other professionals including his banker and business club friends who were also active in finance. He recalled, “Everybody suggested that I put my money in stocks and bonds, either buying them directly or by investing in mutual funds.” As a result he followed his banker’s suggestion and invested in a portfolio of quoted stocks and bonds. By 1998, his net wealth had fallen by 25 percent, not only as a result of that year’s crash but also due to high brokerage fees and taxes.

During our interview Martin concluded that “banks and their relationship managers have a significant conflict of interest with their clients. To maximize profits, the bank has to generate large brokerage fees and other revenues, which is in conflict with the interest of the client, who wants a portfolio that optimizes risk-adjusted returns with minimal transaction costs. The problem is that, even for a very client-oriented bank employee, the interests of the bank prevail because salaries and bonuses are tied to the revenues employees generate.”

When his banker saw that Martin was disappointed with the investment approach, he attempted to propose other investments based on the so-called scientific models such as the Modern Portfolio Theory. But Martin felt unable to assess these options, and he soon became dissatisfied with the hefty fees he was paying: “I had the impression that my banker always wanted to keep the initiative on his side, that he wanted to prevent me from taking responsibility for my own investment decisions.”

After discussions with friends who had similar experiences, Martin concluded that achieving satisfactory returns with his banker, perhaps with any banker, was highly unlikely. But he remained committed to building his personal wealth and achieving an annual return of at least 10 percent on his investments. He knew that he had to radically change his investment approach to achieve this goal.

![]()

Chapter 2

WHY TRADITIONAL INVESTMENT MODELS DON’T WORK

As long as Martin was investing according to his banker’s recommendations he was not able to substantially grow his wealth. Bonds generated only low returns, and he still had to pay taxes on the returns. His stocks went up and down with the market without any reasonable logic. “I realized that with the conventional approach to investing in (quoted) stocks and bonds I would never be able to build real wealth,” he confided in our interview. Why then does the financial industry heavily promote investments in these asset classes?

THE TRUTH ABOUT RETURNS ON STOCKS AND BONDS

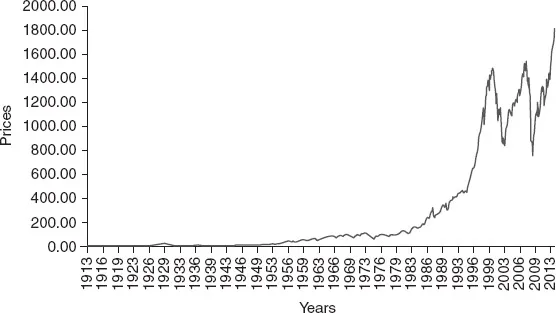

When Martin’s advisors were convincing him to invest in stocks, they used graphs of S&P 500 returns from 1980–2000 which showed an impressive average return of 15 percent. However, if we look over the last 100 years (see Figure 2.1), the annualized S&P 500 return is a fraction of that, at just 2.10 percent.

Figure 2.1 Stock prices as measured by S&P 500, 1913–2013

Source: S&P Capital IQ – capitaliq.com, S&P Historical Price.

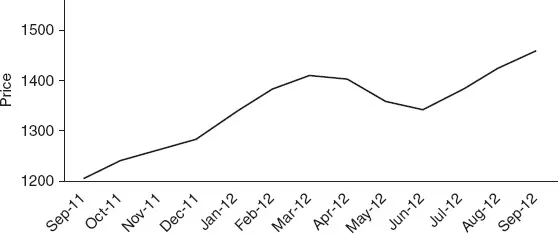

True, with very good market timing – buying in September 2011 and selling in September 2012 – the annualized S&P 500 return would have been 24.83 percent.

Figure 2.2 Stock prices as measured by S&P 500, 2011–2012

Source: S&P Capital IQ – capitaliq.com, S&P Historical Price.

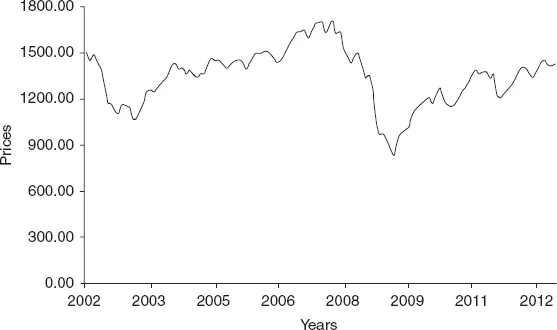

But there is of course the other side of market timing: over the ten-year period from 2002 to 2012, an investor would have lost –0.35 percent.

Figure 2.3 Stock prices as measured by S&P 500, 2002–2012

Source: S&P Capital IQ – capitaliq.com, S&P Historical Prices

Figure 2.3 illustrates that, to create wealth, an investor would have to apply a very difficult market timing. He would have had to invest massively in 2002, stay invested until 2007, sell all stocks in 2007, and again invest heavily in 2008 after the crash. Unfortunately, however, there is a fundamental difficulty in understanding market movements, even in retrospect. As the acclaimed economists George Akerlof and Robert Shiller1 explain:

A similar comparison can be made for investments in stocks in countries other than the United States, with similar conclusions.

For bond investments the picture is even bleaker. Credit Suisse researchers Dimson, Marsh, Staunton, McGinnie, and Wilmot2 calculate the returns for bonds, before taxes and fees, for the period from 1900 to 2013.

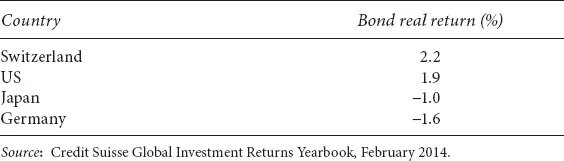

Table 2.1 Bond real returns (1900–2013)

Table 2.1 illustrates that investing in bonds generates only limited real value. In countries such as Germany and Japan, where wars and financial crises (hyperinflation, failure of sovereign debt, etc.) transpired, significant value was destroyed.

In the above examples, we use indices as a basis for our consideration. But is it possible to achieve better results and beat these indices by investing in active managers? What are the chances of succeeding? A review by Cuthbertson, Nitzsche, and O’Sullivan3 examined the performance of mutual funds by analyzing more than 50 studies that were published by the US and the UK between 1990 and 2010, and they report the following:

In other words, positive alpha which indicates that the returns are higher than a benchmark are rarely achieved in the mutual fund industry.

Fernandez and Del Campo4 offer an even more radical example demonstrating that from 1999–2009 only 16 of the 1,117 available mutual funds in Spain (1.4 percent), with a variety of different strategies for investing in shares or bonds, generated returns above the ten-year state bond. The average return was below inflation, and only four had returns above 10 percent, with 263 showing negative returns.

TAXES, FEES, AND OTHER COSTS

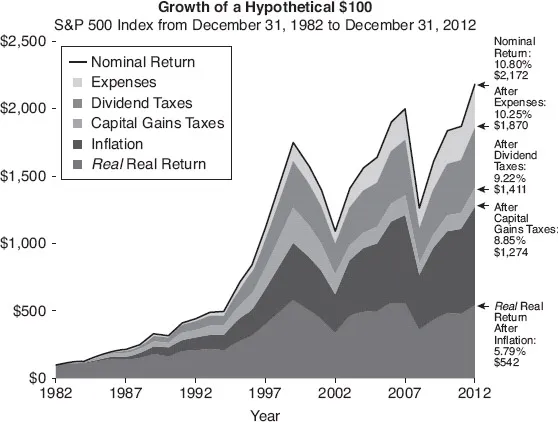

In evaluating investment performance one might easily get caught up in stocks and bonds returns data, but these data alone do not tell the full story. Investors should look carefully at total returns, and real inflation-adjusted returns. A study by Thornburg Investment Management5 calculates returns adjusted for inflation, taxes, and investment expenses – the “real” returns. The study illustrates that in the period between 1982 and 2012, the nominal return of the S&P 500 index was 10.80 percent, but after adjusting for expenses, taxes, and inflation the final return was a mere 5.79 percent (see Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Nominal vs. real returns

Source: Thornburg Investment Management 2013.

THE TEMPTATION TO FOLLOW SIMPLE GRAPHS AND THE CATASTROPHIC EFFECTS OF POWER LAWS

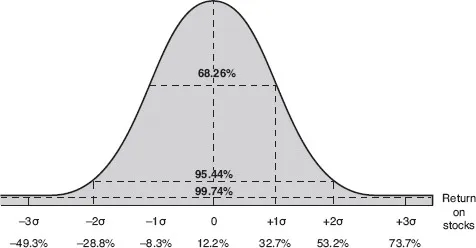

Besides the weak returns of stocks and bonds, another important factor contributing to poor portfolio performance is that the models applied by most academicians and financial experts do not give a true picture of expected performance due to simplified models and the application of the standard deviation as a basis for returns expectation. In their popular finance textbook, Corporate Finance, Ross, Westerfield, and Jaffe6 explain that with a large enough sample of stock market returns and a long enough observation period (about 1,000 years), distribution of returns would form a “Normal” bell-shaped curve as shown in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5 The Normal Distribution

Source: Ross Stephan, Westerfield Randolph and Jaffe Jeffrey, 2010 Corporate Finance, 247–249.

This would be excellent news since Brealey and Myers7 point out that “Normal Distributions can be completely defined by two numbers: one is the average or expected return (the historic mean of observed returns) and the other is the variance or standard deviation. They are the only two measures that an investor needs to consider.”

However, looking at the Normal Distribution of Figure 2.5, a hypothetical investment portfolio with a historic average return of 12.2 percent could with a probability of 68.26 percent generate an investment return between –8.3 and 32.7 percent! Returns based on this commonly used “Normal Distribution” would sometimes be positive and sometimes negative across a broad performance range.

The key mathematical concept of what constitutes a Normal Distribution was developed by Carl Friedrich Gauss, considered one of the seminal mathematicians of the nineteenth century. Not surprisingly, quantitative economists of the first half of the twentieth century were keen to use Gauss’s concepts to construct models for optimal portfolio construction, particularly because of its simplicity, which led to the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), optimizing return and risk, and the Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT). As these mathematical models gained wider industry acceptance, they evolved into a marketing tool for advisors who claimed that their advice was based on the work by Nobel prize-winning academic researchers. Until today, many financial institutions use this classic concept of risk management, standard deviation, and other measurements, based on the Normal Distribution.8

SO IS INVESTING A BELL CURVE GAME?

The question is whether stock market returns follow a Normal Distribution. Research conducted in the late 1990s and early 2000s suggest that the hypothesis of Normal Distribution does not conform to many events in the financial markets. Marcus Dav...