eBook - ePub

Co-operative Innovations in China and the West

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Co-operative Innovations in China and the West

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book aims to contribute to our understanding of recent changes in Chinese and Western cooperatives. It will provide a variety of audiences with relevant and useful information for further co-operative development, mutual understanding and cooperation.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Co-operative Innovations in China and the West by C. Gijselinckx, L. Zhao, S. Novkovic, C. Gijselinckx,L. Zhao,S. Novkovic in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Global Development Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

General Analysis of Trends and Evolutions in Co-operatives in the West

1

Features and Determinants of Co-operative Development in Western Countries

Patrizia Battilani

Introduction

The Barcelona football club is a co-operative, as are many prestigious European winemakers. Surfing the Web, you can find the site of the Nursery School of Old Saybrook, Connecticut, a small community co-operative owned and managed by parents whose children attend the school. Arla Foods is a big agri-food co-operative which owns some 150 companies around the world. The above picture is not surprising to scholars who have some familiarity with this form of enterprise: the co-operative world has been one of diversity since its beginnings. In 1937 the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA) adopted the 1844 Rochdale principles as a set of guidelines to provide a universal framework which would strengthen the identity of this form of enterprise. That was also the first attempt to define a universal model whose origins must be traced in the European experience. When, in 1966 and 1995, that set of principles was revised, the Western countries’ co-operative movement remained the reference point.

Starting from the above considerations, we will analyse the evolution of Western co-operatives, looking for diverse and shared features. Sections one and two are devoted to identifying the basic elements of the Western co-operative story. The remaining sections focus on the main factors which can explain the evolution of this form of enterprise in Western countries: state promotion, networking and cultural views.

At the end of the day a composite picture emerges in which two aspects deserve particular attention. In the West, co-operative development has for the most part been a bottom-up process in which government policies played a marginal role. The most effective long-term policies, where they existed, were those aimed at supporting the institutional viability of co-operatives. In addition, networking and members’ cohesion, related to the sharing of cultural views, have certainly helped co-operatives’ growth and competitiveness.

Co-operative beginnings in Western countries

The two key aspects of the long history of co-operative enterprises in Western countries are their origins, which date back to before the industrial revolution, and the bottom up process that generated them.

The first feature is in contrast to the prevailing literature, which links the birth of co-operative firms to the Industrial Revolution. In 1908, Fay, in the very first geography of co-operatives across Europe, provided an historical overview based on interviews and documented records. The author dated back the origins of co-operatives to the 18th century. Already in 1760 corn mills were founded on a co-operative basis as a countermeasure against the high prices set by the corn millers who held the local monopoly (p.14). However, as Cole stated 40 years later (Cole 1944), the first co-operatives ‘were not followed up, and never constituted a movement. They were isolated experiments; and no one knows now who inspired most of them’ (p.15). Eventually, during the first half of the 20th century, when books and pamphlets on co-operative enterprises were published, a literature of their development appeared as well and connected their diffusion to the social disruption and economic thought generated by the Industrial Revolution. In addition, co-operative enterprises were considered as being a part of a wider movement deeply rooted in 19th-century social and political attitudes. This version has been often re-circulated (Birchall 1997).

However more recent studies on the Middle Ages leave room for questioning the above conviction. The 1997 paper by van Driel and Davos pre-dated the origins of co-operatives to as early as the 14th and 15th centuries in Belgium and Holland. Indeed, the Antwerp naties and the Dutch vemen were organized in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, respectively. Both were set up as co-operatives of porters or other auxiliary merchants’ workers. These structures exhibited many features of modern co-operatives. We shall take, for example, the ‘one member, one vote’ principle, or the habit of collecting revenues from each member in order to periodically share within the co-operative (van Driel and Davos 1997).

It is also important to recall the regulated companies set up by merchants in the England in the 15th century, which followed the one member, one vote rule. Adam Smith, in his The Wealth of Nations, compares the regulated companies to the emerging joint stock companies, so to focus on what he considered to be the main weaknesses of this form of enterprise: the ‘corporation spirit’ (p.580) and the open-door principle. The latter actually obliged the firms ‘to admit any person, properly qualified, upon paying a certain fine’ (Smith 1812:579).

Therefore, we could conclude that co-operatives appeared in the 15th century, at the dawn of the market economy. However only in the age of the Industrial Revolution, and particularly during the 19th century, did co-operatives catch experts’ and politicians’ attention together with the support of the various social and political movements of the time. In the century when commercial codes made their appearance (Ripert 1951), co-operative enterprises gained legal status. In many countries the deregulation of limited liability companies was the occasion to enter the definition and regulation of co-operative enterprises into the commercial code (Guinnane and Martínez-Rodríguez 2010; Battilani and Bertagnoni 2010). The 19th-century institutional innovations did not have the purpose of strengthening only investor-owned enterprises; they also included the concept of undertaking, through which ownership was assigned to stakeholders who were not investors – in other words the co-operative.1 The first countries to provide a legal framework for this form of enterprise were the Austrian Empire and Belgium. In many countries the new laws were the expression of liberal ideals which considered co-operatives a possible solution for social issues.

In conclusion, since their beginning, Western co-operatives showed aspects of voluntary organizations and emerged as a result of a bottom-up process driven by values and social inspirations which sometimes changed over time. Very often worker, religious and economic movements had an impact in shaping and fostering this form of enterprise (Schneiberg, King and Smith 2008).

Western co-operatives after World War II

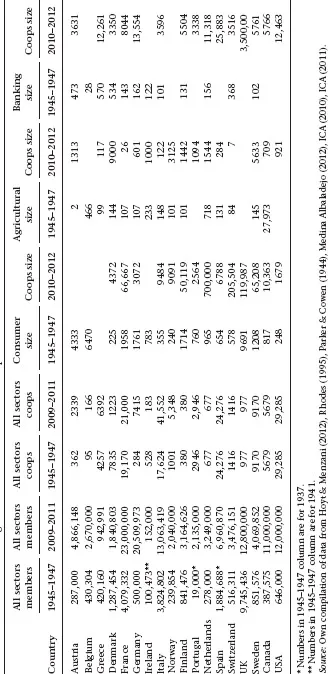

Due to a lack of comparative data on co-operative enterprises, only a very rough sketch can be made of the evolution of co-operatives in Western countries after World War II.2 To this end, I will use two benchmark years (1947 and 2009) with data on membership from various sources.3 The results are compiled in Table 1.1. Three aspects stand out over the long run. First of all, the number of members has been increasing in almost all Western countries. Secondly, co-operatives have become larger. Thirdly, the size mainly increased in what we can consider the traditional co-operative sectors: consumer, credit and agriculture. Indeed, if we take into consideration the 300 largest global co-operatives and mutual organizations in the world – including their associated companies – (ICA 2011) we will notice that nearly 80 per cent of the overall turnover (revenue) is represented by the following sectors: food and agriculture (33 per cent), insurance (22 per cent), retailing/wholesaling (25 per cent).

Therefore, we could describe the evolution of Western co-operatives in traditional sectors as acquiring a larger size to exploit economies of scale and to invest in innovation or marketing. Take, for instance, the agricultural sector. Since the 1950s many European co-operative leaders claimed the need to change the basic structure of the sector by limiting the number of nationwide co-operatives. In some cases the rationalization became an issue before World War II. In Denmark, in July 1937, the government established the first commission promoting amalgamation in the dairy sector, but the publication of the commission’s report was interrupted by the war (Svendsen and Svendsen 2004). When it became public in 1949 the report stated that: ‘large dairies are better capable of implementing the needed technological innovations that can ensure the best quality products’ (Svendsen and Svendsen 2004:114). In general the amalgamation process became a common feature in the European co-operative movement during the 1960s and the 1970s.4 Rationalization and amalgamation not only increased the market power of farmers but, more importantly, enabled them to take part in the development of agro-industry and to consequently obtain an increasing share of the value of their production. Since then mergers and acquisitions never stopped.

Table 1.1 Members and average size in terms of members of co-operatives in Western countries 1947 and 2009

However the creation of big enterprises is only one part of the story. Small undertakings are still an important share of the European co-operative movement, above all outside the traditional co-operative sectors. Take, for instance, the setting up of many small social co-operatives in Italy in the last few decades (Borzaga and Ianes 2006).

We could ask what factors stimulated the multifaceted evolution of Western co-operatives during the second half of the 20th century. Among the many determinants that explain success and failure of co-operative enterprises analysed in the literature, we focus on three features: state intervention, networking, and cultural views.

The determinants of co-operative development: state intervention

There is a long tradition of claims that co-operatives should be supported by the state, especially in the initial stage of their development. The origin of this approach can be traced back to the French thinker, Louis Blanc, according to whom co-operatives are a form of organization promoting the public interest (Blanc 1839) because they could provide a solution to unemployment. Therefore, according to Blanc, a government should support co-operatives in their early stages by purchasing production equipment or giving public procurement, and should withdraw its support once co-operatives become viable. The first attempt to implement this project was made during the Revolution of 1848, when the provisional government and Blanc himself created the National Workshops: laboratories in which unemployed urban workers were given a job to carry out useful public works. However, this first experiment was unsuccessful.

Nevertheless, after World War I in some European countries (for example, Italy and France) the government fostered the development of co-operatives because they were considered a good tool to fight not only unemployment but also inflation by granting free land to cultivate, giving public works without tender, or providing low-interest loans (Caroleo 1986). In the second half of the 20th century this kind of public intervention in favour of co-operatives became less and less practiced.

The second type of state intervention, much more intrusive for co-operative life, dates back to the Russian Revolution. It consisted in the promotion of a different kind of enterprise: the state-centric co-operative, in which the state or the party in power takes over traditional co-operatives. In Western Europe this solution was adopted by Fascist and Nazi regimes during the interwar years (Menzani 2009, Kramper 2009) in order to politically control the co-operative movement.

However, after World War II the state-centric co-operatives disappeared in Italy, Germany and Western countries in general, even though the state was occasionally taking over co-operatives in those decades, too, as for example the mutuals in Germany, which were included in the public security system of the country during the 1960s.

In the same decades, however, state-centric co-operatives kept spreading in all command economies as well as in many former European colonies in Africa and Asia. This divide would be overcome only after the collapse of the Soviet Union with the transition to the market economy in Eastern and Central Europe. Generally, the promotion of state-centric co-operatives did not prove to be very successful, above all when the strategy included general state support and dependence. In those countries it did not help the diffusion of viable autonomous co-operative enterprises and, in addition, it contributed to the lack of understanding and a negative public image, even for member-based co-operatives. The third kind of state intervention we consider, namely the approval of legislative measures to ensure proper functioning of co-operative enterprises, demonstrate markedly different results compared to the other two types of intervention. During the 1960s and the 1970s, the adoption of mainstream economic models in analysing co-operative firms focused on the many alleged weaknesses of this kind of enterprise (Furubotn and Pejovich 1970; Ward 1958; Vanek 1977).5

A clear example is the undercapitalization (and underinvestment) of co-operatives, an issue on which a complex and protracted debate took place (Pencavel 2001; Dow 2003; Perotin 2012). A variety of suggestions came from those empirical and theoretical studies, from the adoption of tax incentives to the creation of membership markets.

In the end, the result of all of this was not the disposal of co-operatives but rather the development of legislative measures aiming at ensuring their proper functioning, so to overcome their potential weaknesses. As for the under capitalization, UK legislation enabled the creation of a market for membership rights. However, very often these co-operatives were converted into traditional companies after a few years. Take, for instance, the worker-owned bus companies that resulted from privatization in the 1990s; after some years they were sold to conventional owners (Perotin 2012).

This means that these legislative measures were actually more favourable for investor-owned companies than for co-operatives, thereby leading to demutualization, even though they may have seemed to offer a solution for undercapitalization and the long-run growth strategies of co-operatives. An alternative solution to the underinvestment issue...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I General Analysis of Trends and Evolutions in Co-operatives in the West

- Part II Sector-Specific Analysis of Trends and Evolutions in the West

- Part III Trends and Evolutions in Chinese Co-operatives

- Index