![]()

Part I

Economic Growth and Structural Transformation

![]()

1

Structural Transformation

Doerte Doemeland and Marc Schiffbauer

1.1 Introduction

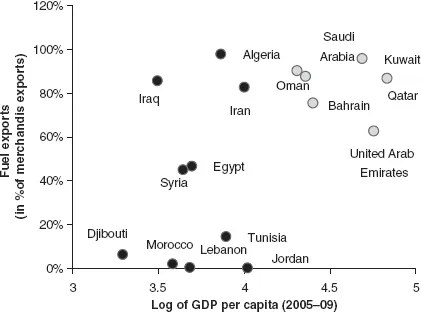

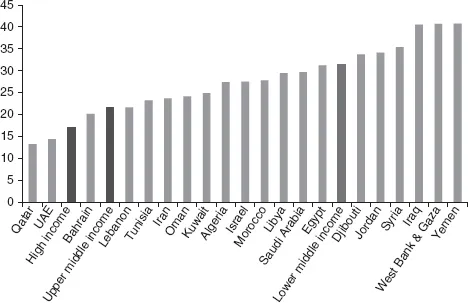

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is an economically diverse region. It encompasses oil-rich, high-income Gulf countries and resource-scarce, lower-middle-income countries, such as Djibouti, Morocco, West Bank and Gaza and Yemen (Figure 1.1).1 The countries are also very different in their demographic structure. There are relatively few young people as a share of the population in Qatar and United Arab Emirates, while in Iraq, Yemen and West Bank and Gaza more than 40 percent of the population is younger than 15 years of age (Figure 1.2). Moreover, while the Gulf states are net migrant recipients, all other MENA countries, including natural resource-rich countries such as Algeria, Iraq and Iran, export migrants.

Though per capita growth in MENA has been broadly in line with other regions, the contribution of productivity growth to overall growth has been very weak. MENA’s growth has to a large extent been driven by demographic change, here defined as the change in working-age population as a share of the total population and contributed about 50 percent to economic growth. High fertility rates combined with rapidly declining mortality contributed to a sharp increase in MENA’s working-age population as a share of the total population and has rapidly increased MENA’s potential labor supply.

The objective of this chapter is to analyze MENA’s growth performance through the prism of structural change. Using a newly developed data set, it assesses the role of structural change in explaining MENA’s growth performance. In particular, it analyzes the contribution of productivity growth at the sector level, within sectors, and due to reallocation of workers across sectors, to overall economic growth. It also provides empirical evidence as to which factors may have contributed to MENA’s slow structural change and discusses unconditional convergence within MENA’s manufacturing sector.

Figure 1.1 GDP per capita and fuel exports

Source: Authors’ calculations based on WDI. Daata for Libya, West Bank and Gaza and Yemen are missing. Dark grey circles are developing countries, light grey circles high income countries.

Figure 1.2 Percentage of population younger than 15

Source: Authors’ calculations based on WDI. Dark grey bars are country group averages.

The chapter is structured as follows. First, it provides an overview of MENAs growth performance over time and relative to other regions. Then, it present patterns of labor productivity growth in the MENA region, before assessing structural change and its determinants. Next, it provides a discussion of unconditional convergence within manufacturing. The final section concludes.

1.2 MENA’s growth performance

With the exception of Asia, MENA’s growth in per capita terms has outperformed all other regions during the last two decades. After a prolonged economic stagnation during the 1980s, growth in MENA recovered in the 1990s as governments shifted away from state-led economic models towards more private-sector led economic policies and promoted global integration. Thanks to increased global integration, export growth, even when excluding minerals and fuels, surged above the average of developing countries. Between 1991 and 2012, real GDP growth per capita averaged 2.2 percent in constant terms, outpacing all other regions with the exception of South Asia and East Asia and Pacific. This good growth performance was not driven solely by MENA’s oil exporting high-income countries. Real GDP per capita growth was also strong among MENAs developing countries, averaging 2.1 percent between 1991 and 2009 and accelerating to 2.6 percent between 2000 and 2009.

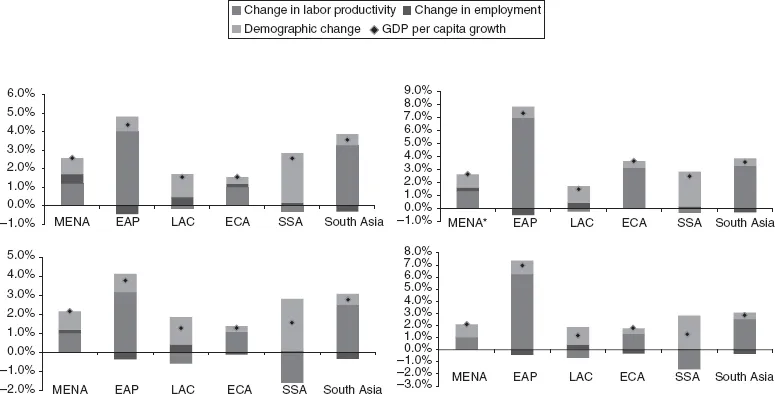

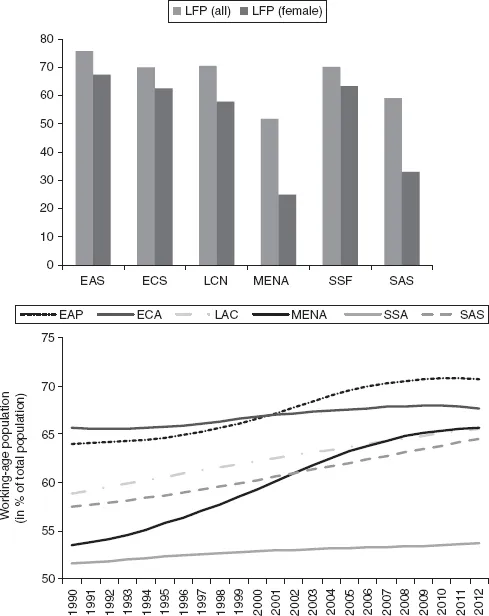

In no other region was growth as strongly associated with demographic change as in MENA. Demographic change, which is the change in working-age population as a share of population, contributed about 50 percent to economic growth (Figure 1.3). The MENA region has the second highest population growth rate in the world. Its population growth rate between 1990 and 2021 averaged 2 percent and was only surpassed by population growth in Sub-Saharan Africa, which averaged 2.7 percent over the same period. High fertility rates combined with rapidly declining mortality contributed to a sharp increase in MENA’s working-age population as a share of total population (Figure 1.4), rapidly increasing MENA”s potential labor supply. Though its demographic is often blamed for MENA’s economic vows, the relative size of the labor force is a key determinant of country’s income level. If the share of working-age population in total population increases, labor supply tends to increase and with it the economy.

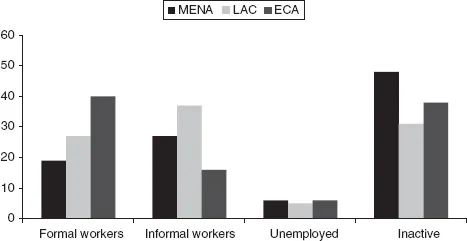

Riddled with structural constraints, many MENA economies have not been able to absorb a fast increasing labor force. Formal sector workers as a share of the working-age population in MENA are much lower than in other middle-income regions like Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and Eastern Europe and Central Asia (ECA). Unemployment and inactivity, in particular among women, are also more prevalent. Less than a quarter of all working-age women in the MENA region participated in the labor force in 2012. This compares to over 60 percent in East Asia and Pacific, Eastern Europe and Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 1.5).

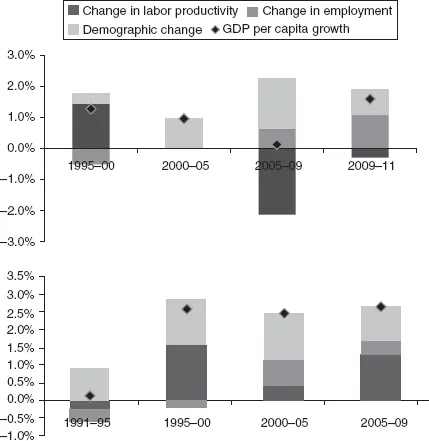

Figure 1.3 MENA’s growth performance

Figure 1.4 Demographic change

The contribution of productivity growth to GDP growth was low in MENA compared to other countries in the region. Change in labor productivity explains about 49 percent of real GDP growth of MENA’s developing countries over the last two decades which is significantly less than that of any other regional growth with the exception of LAC. For the MENA region as a whole per capita growth accelerated between 1995–2000 and 2000–2005 as demographic change, measured as the growth of the working-age population as a share of the total population, accelerated. In MENA’s high-income countries, the change in labor productivity has not been positively associated with economic growth in the last 15 years. Productivity growth, however, was much more strongly associated with growth in MENA’s developing countries or non-oil exporting countries, contributing more than 50 percent to real GDP per capita growth between 1995–2000 and 2005–2009 (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.5 Composition of working-age population

Source: Authors’ calculations based on WDI. World Bank. 2013. Based on ILO-KILM database.

**Refers to selected countries for ECA, LAC and MENA for 2012.

MENA’s weak economic performance is often attributed to the Dutch disease. Inflows in foreign exchange generated from natural resource exports can lead to a downward pressure on the exchange rate and an upward pressure on domestic prices, resulting in real exchange rate appreciation. This can lead to a crowding out of other tradable goods, for example in the manufacturing sector. There are good arguments why diversification into manufacturing or other non-resource tradable goods might be necessary to achieve higher income.2 In addition, since volatility of commodity prices propagates to revenues, resource richness can complicate fiscal management and if permeated to aggregate spending, increase real exchange rate volatility, which can act as a tax on investment. Even oil-poor countries are sensitive to changes in the oil price because a large part of their economies depends on work remittances, aid and tourism revenues from oil-rich countries (Dahi and Demir 2008). It has also been argued that the adoption of pegged or fixed exchange rate regime to shelter oil-rich economies from oil price volatility lead to a real exchange rate overvaluation and thus losses in competitiveness of the region (Nabli and Veganzones-Varoudakis, 2002; Diop and Marotto, 2013).

Figure 1.6 Real GDP per capita decomposition of high income and developing MENA countries

a) High income MENA countries b) Developing MENA countries

Source: Authors’ calculations based on WDI.

Notes: High income countries do not include Qatar because of lack of data.

But equally often state-led economic policies have been blamed for MENA’s weak economic performance. From independence to the late 1980s, the region’s economic policies were dominated by state-led import-substitution models. Oil discoveries combined with successive increase of petroleum prices fueled economic growth. Supported by oil revenues, governments implemented a wide range of industrial polices to support the manufacturing sector. In the early 1990s, most MENA countries recognized that the state-led import-substitution models had run out of steam. They introduced reforms aimed at shifting towards a more private sector-led economy, integrating their economies with the rest of the world and reducing the oil dependence of their economic base. Still, the private sector reform agenda fell short of containing distortionary government interventions and creating a level playing field for all business. With the exception of the Maghreb countries, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia and Libya, MENA countries tend to be less open in 2012 than in 1990. And with the exception of Qatar and Tunisia none was able to significantly reduce fuel exports as a share of total exports.

In this chapter we analyze MENA’s structural transformation with a view of identifying opportunities for accelerating productivity growth. In particular, it discusses productivity growth at the sector level and productivity growth driven by a reallocation of workers across sectors. It could be argued that increased productivity growth doesn’t only boost growth but also labor demand over time.

1.3 Change in sector productivities and employment shares

One of the key insights of development economics is that growth is driven by a structural shift from agriculture to manufacturing. This sectoral shift tends to be mirrored in the pattern of employment so that over time the labor force in the nonagricultural sector increases while employment in the agricultural sector declines. As labor moves to the industrial sector, overall productivity rises and incomes expand. Reallocation of workers from one sector to another is hence an important aspect of economic development. One of the traditional work-horse models of structural transformation, the surplus labor model (Lewis, 1954) illustrates the indispensability of labor reallocation. It assumes that a traditional (agricultural) and a modern (industry) coexist. Ranis and Fei (1961) divide the development of surplus-labor countries in several stages. In the first stages, surplus labor in the agriculture sector is pulled towards the nascent industrial sector. The economy’s wage level and agriculture output remain unchanged. Still, the marginal product of labor is below the wage level. In a next phase, workers who are producing agriculture output but earn less than the wage level move to the industrial sector and agricultural output declines. The nominal wages in the industrial sector rises. In the last stage, farm workers who produce output equal to their wages move to industry and agriculture productivity increases. The faster the reallocation from agriculture to industry the faster growth materializes.

Over time, economics have moved to a three-sector view of structural change. As incomes continue to rise, people begin to demand more services. In fact, in many countries the share of the service sector in GDP rises almost linearly. Still, labor productivity of services does tend to grow less than of agriculture and industry because many service jobs require manual labor. In fact, labor productivity in the service sector as a share of average labor productivity tends to rise at lower levels, then declines over an intermediate range, before increasing again in the OECD (Eichengreen and Gupta 2014). The second surge is most likely caused by the rise of the modern service sector, which includes business services, telecommunication and finance.3 In most industrialized countries, the service sector has become the dominant sector

Contrary to all other regions, services did not increase as share of GDP in MENA (Figure 1.7). As expected, agriculture has declined as a share of GDP between 1990 and 2011 in all regions of the world, but so did manufacturing. In fact, services increased as a share of GDP in all regions except for MENA. The decline in MENA’s service is particularly striking since public wage bills (which are the key component of public sector value added) have increased significantly during the period and the public sector is subsumed under services. The production of services tends to require relatively less natural capital and more human capital than the production of agricultural or industrial goods. The decline in the share of services is likely to be one reason why unemployment of highly educated workers has been high in some countries, such as the Arab Republic of Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia and Morocco.

More detailed data reveal significant differences in labor productivity growth across sectors between 2000 and 2010. In Jordan and Morocco, for example, labor productivity growth was driven by improvements in agriculture, manufacturing and mining. Tunisia and Morocco also experienced strong labor productivity growth in transport and telecommunication and government services whereas financial and business services were a drive of productivity growth in Jordan.

Contrary to more advanced economies,...