Satan , Lucifer, Baal, Moloch, Leviathan, Belfagor, Lilith, Chernobog, Mammon, Vitra, Azazel, Loki, Iblis, Mara, and Angra Mainyu are only a few of the names given to demons from various religions (Van der Toorn et al. 1999). For those who believe in the demonic being, he or she is an entity that brings evil into the world and is working, often from a distance, to push humanity towards temptation and, sometimes, destruction. To protect themselves from this evil influence, people have used the most varied practices. They may pray, lead an ascetic life and/or use protective talismans. But what happens when we are convinced that we are face to face with the devil? Or even with someone that is possessed by this entity? Although the ritual of exorcism is practised in many religions (Oesterreich 1930), social scientists, apart from anthropologists in post-colonial countries, have, so far, given it little attention in today’s western societies. Sociologists of religion , perhaps considering that in industrial societies the figure of Satan is merely a legacy of the superstitious and obscurantist past, seem to have shelved this issue, probably believing it to be totally out-dated.

Actually, in recent years, reports of interest in the occult

world and in the rituals that release individuals from demonic possession have increased, becoming more and more widespread among broad segments of the population (Baker

2008; McCloud

2015), thus justifying a renewed interest on the part of certain religious institutions. In the US

,

Gallup polls show that the percentage of people who believe in the

devil has increased from 55 per cent in 1990 to 70 per cent in 2004. Baker (

2008, p. 218) analysed the data collected by the first wave of the

Baylor Religion Survey which was conducted in 2005, and discovered that in the US

African Americans tend to have a stronger belief in religious evil than do whites. Women have a stronger degree of belief than men. Net of religious controls, younger Americans hold stronger belief in conceptions of religious evil than older Americans. Finally, social class plays an important role in how certain an individual is about the existence of religious evil, with those of higher social class having weaker confidence about the existence of religious evil. However, these effects are conditioned by church attendance. For those exhibiting a high level of participation in organized religion , the influence of social class is neutralized. For those not actively participating in organized religion , the influence of social class is more pronounced.

The 1998 Southern Focus Poll in the US

, which had a sample of 1200 people, posed a question much closer to the notion of exorcism. In this poll, close to 59 per cent of respondents answered in the affirmative to the question: ‘Do you believe that people on this Earth are sometimes possessed by the

Devil?’ (Rice

2003). The second wave of the Baylor

Religion Survey, in 2007, posed the question: ‘Is it possible to be possessed?’ In answer, 53.3 per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that it is possible. Among those who attend church once or more than once a week the proportion of respondents answering in the affirmative increased to 77.9 per cent. Republicans (65.9 per cent) were more likely than Democrats (42.7 per cent), and Protestants (62.9 per cent) were more likely than Catholics (53.3 per cent) or those professing to follow no

religion (19.5 per cent) or the Jewish population (3.6 per cent) to agree or strongly agree that it possible to be possessed by the

devil . In

Italy , according to the Association of Catholic Psychiatrists and Psychologists, half a million people per year would undergo an exorcism (Baglio

2009, p. 7).

It is difficult to find accurate figures for the number of people who have been subjected to exorcism, and so proving in a rigorous way that the incidence of the practice is increasing is extremely problematic. Even if we were able to show a statistical increase, would this imply an increase in actual numbers or just in visibility? Indeed, many exorcisms take place ‘underground’, but if they become more public and hence noticeable, this does not necessarily mean that more are being conducted. We also need to agree on what exorcism means. Do we include only the rituals concerned with removing an unwanted spirit from a person’s body, or does exorcism also include a ritual or practice that protects people from a demon’s influence? Should we take into account the ministry of deliverance (see Chap. 5) among Pentecostal groups, that is directed towards delivering people from the presence of the devil , rather than from physical and mental possession by the devil? This ministry is certainly gaining popularity and is becoming more mainstream, but it is a specific practice that is not defined by everyone as exorcism.

Instead of demonstrating an increase in instances of exorcism, we can show evidence of an increase in people’s sense of the normality of this practice. More and more, people are believing in the presence of the devil and in the possibility of being possessed. For example, to help move the debate forward, this book turns to new data resources provided by Google (and, more specifically, Google Ngrams) which has plans to digitize every book ever printed. According to Alwin (2013), this site had, at the time of his comment, more than 15 million scanned books, representing 12 per cent of books ever published. There are, of course, certain issues to take into account when using these new internet social research methods, but we invite the reader to access Groves (2011) and Savage (2013), for example, to explore this matter further.

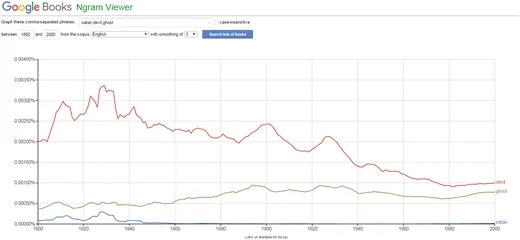

We typed the key words ‘

devil ’, ‘

Satan ’ and ‘

ghost ’ (see Chap.

3) into the

Ngram Viewer on

Google Books , which reports the proportion of references to a given word or combination of words as a percentage of the total corpus (Savage

2013). As shown in Fig.

1.1, among all the books held in

Google Books , the word ‘

devil ’ has been slightly more popular than ‘

ghost ’ and ‘

Satan ’. However, the usage of these terms has been in decline since the 1840s. Thus it could at least be argued that people are discussing the notions of the

devil ,

Satan and

ghosts less in books and this indicates that these notions are less relevant or important today than they were in the past. Unfortunately,

Ngram Viewer offers no way to understand how these words were used in the literature, and the use of the word ‘

devil ’ can be questioned. Does it refer to a

demon , as a specific type of religious entity, or to a person who has some devilish characteristics reflecting a cruel side.

Google Trends gives an analysis of the use of keywords entered into the Google search engine since 2004. On our entering the same three key terms, it was shown that use of the term ‘

devil ’ peaked when the movie

The Devil Wears Prada was released in 2006, and the term ‘

ghost ’ was most popular when the Playstation game ‘Call of Duty:

Ghosts ’ was released in 2013. Since the outcome of this kind of analysis is not relevant for this present research,

Google Trends was not used as a research method. Returning to

Ngram we can see that since the mid nineteenth century the usage of these three words (whatever they may mean in their particular contexts) has been in decline, though since the 1980s they have made a slight comeback; it is clear that the nineteenth century was the heyday for their usage.

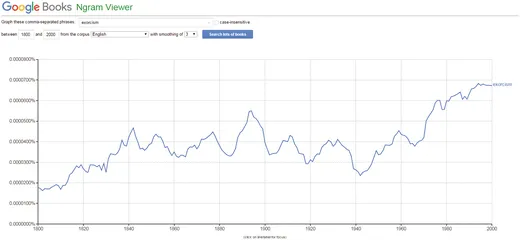

However, with regards to ‘exorcism’, the case is quite different. As this word is less ambiguous than ‘

ghost ’, ‘

devil ’ or ‘

Satan ’, the data collected here are more meaningful. If we compare the term ‘exorcism’ to the three above-mentioned terms, its number of instances is too low to appear on the graph in Fig.

1.1. Therefore, in Fig.

1.2, this term is analysed on its own.

Figure 1.2 shows that, in contrast to the decline in the use of ‘devil ’ and ‘Satan ’ in the books scanned by Google, the use of the word ‘exorcism’ has been on the increase since the 1940s and again since the 1970s. Although there was an important peak at the end of the nineteenth century, it is clear that this word is used today more than at any time since the 1800s.

Popular culture, especially the 1973 movie, the Exorcist , and the 1975 account of Malachi Martin’s (1992) Hostage to the Devil: The Possession and Exorcism of Five Living Americans , has been instrumental in revitalizing a belief in exorcism in the western world, touching and impressing millions of readers and viewers and bringing the notion of exorcism back into people’s consciousness (Cuneo 2001). However, rather than seeing these works as a causative factor in this renewed interest, it might be more appropriate to see them as catalysts to wider social and cultural changes brought about by late modernity.

In our post-industrial society, despite the increase in education, urbanism, and scientific knowledge, science no longer dominates our way of thinking and expert scientists are no longer believed implicitly. We have also entered the era of a globalized world, and multicultural and multi-faith scenarios are part of our everyday lives. Religions ,...