eBook - ePub

The Global Gold Market and the International Monetary System from the late 19th Century to the Present

Actors, Networks, Power

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Global Gold Market and the International Monetary System from the late 19th Century to the Present

Actors, Networks, Power

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Using an inter-disciplinary and global approach this book examines the different roles gold played in the international economy from the late 19th century until today. It gives a complete and comprehensive overview of the many facets of the global gold market's organization from the extraction of this precious metal to its consumption.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Global Gold Market and the International Monetary System from the late 19th Century to the Present by S. Bott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Financial Services. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Global Gold Market and the International Monetary System

Catherine R. Schenk

For most of the history of civilization, gold has played an enduring role as a store of value, means of exchange and unit of account. These are the three properties that traditionally define ‘money’, and indeed gold has periodically been at the core of national and international monetary systems. Gold has acted most consistently as a store of value, and this has generated a highly developed global market in gold and in gold derivative products. Gold’s physical attributes, scarcity and geographic distribution have combined to ensure that it remains a precious and sought-after mineral. Physically, gold is malleable, heavy and robust, features which make it suitable for easy storage, transport and division into a range of standard denominations. Moreover, scarcity and the cost of mining or extracting gold sustains its value over the long term, although there have been periods of wild fluctuations in relative gold prices that mean that it is best accumulated as part of a diversified portfolio of assets rather than a single store of value. This chapter argues that the monetary and commodity roles of gold have been closely intertwined historically, with profound effects on the global gold market.

While trading in gold likely began at the time when it was first used for ornamentation, the global gold trade took many centuries to develop. By 1300 the goldsmiths in London had worked to define the value and quality of gold through hallmarking, but the shortage of gold from European mines restricted its circulation as coinage and pushed exploration further afield. While the softness of the metal made it easy to mould into ornaments and to mint into coin, it also made it quickly degradable through chips and rubbing. Hence, once higher-quality technology was available to mint base metal coins, the advantages of gold receded. As a result, gold came to be used mainly for larger transactions and as a store of value among the wealthier classes.

The powerful Venetian empire used its commercial and political links to bring gold from Africa and Central Asia as part of the exercise of its wealth, striking 1.2 million gold ducats in 1422.1 Likewise, the Spanish state’s hunger for gold drove the exploitation of the American continents through the 16th century (on the monetary, social and cultural disruption this caused for Spain, see Vilches 2010). During the period of mercantilism in the 16th to 18th centuries the economic imperative for many states was to accumulate as much treasure and wealth in central coffers as possible. Gold was an important determinant of the ability to defend a sovereign’s power and influence in an era of costly national and international conflict.

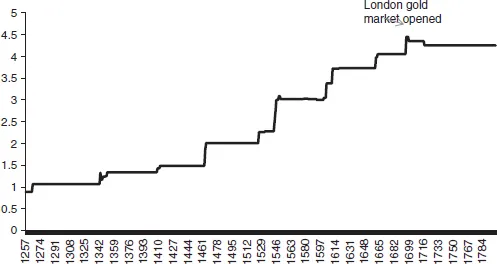

Economies of scale and scope ensured that London developed into the world’s largest gold market, attracting customers from throughout Europe and beyond. Although gold is not produced in quantity in the British Isles, London offered a natural home for the metal, as London emerged as the world’s dominant international financial and commercial centre in the 18th and 19th centuries. Figure 1.1 shows the official gold price in London as recorded by Officer and Williamson from 1254 to 1799 (2011).

Despite prolonged periods of relative stability, this data shows the relentless inflation in the gold price (or the depreciation of the British pound) during those centuries. From 1696 the London market became more formalized, and the price was eventually stabilized at £4.25/oz2 from 1717. This marked the beginning of the gold standard for the UK, whereby the value of the pound was fixed by statute to a weight of gold. Gold circulated as coin alongside paper notes, and the national money supply was partly determined by the flow of gold in and out of the country due to fluctuations in the balance of payments. Other countries that did not have substantial gold reserves preferred to denominate the value of their currencies either in silver (silver standard) or in silver and gold (bimetallic standard) (for a survey of bimetallism see Redish 2000). France, for example, minted both gold and silver coins that operated as legal tender and circulated side by side, supported by the Banque de France fixing the relative prices of the two metals (Flandreau 2004). France led the Latin Monetary Union, which persisted with the bimetallic standard until the 1870s (other members included Belgium, Italy and Switzerland). The USA and German states were the other major economies that embraced bimetallism until the 1870s, while Mexico, India and China were on a silver standard.

Figure 1.1 Official London Gold price 1257–1799 (GBP per ounce)

Source: Officer

Lawrence and Samuel H. Williamson (2011).

By the end of the 19th century the value of silver was falling sharply, encouraging more countries to link to gold rather than suffer the pressures of linking to a depreciating standard. Moreover, when gold was in the ascendency it tended to be hoarded, leaving the less valuable silver coins in circulation (a phenomenon known as Gresham’s Law). Under pressure from the expenses of the Napoleonic Wars and a bank run when a French victory seemed likely, convertibility of Bank of England notes into gold was suspended in February 1797 and only restored in 1819 after a decade of vigorous debate. The ‘bullionist controversy’ pitched those who wished to restore the gold anchor to the Bank of England’s note issue to restrain inflation against, on the one hand, proponents of the Real Bills Doctrine and, on the other, the Bank of England. The Real Bills Doctrine suggested that gold convertibility was not the only way to operate a stable monetary system so long as the Bank of England only discounted bills that were self-liquidating (so-called ‘real’ bills) (de Cecco 1997, pp. 62–80). In the end, the Bullionists won the debate, and in 1819 convertibility was mandated to be restored, effective from 1821. However, this was only the beginning of the controversy over the role of gold in the international monetary system.

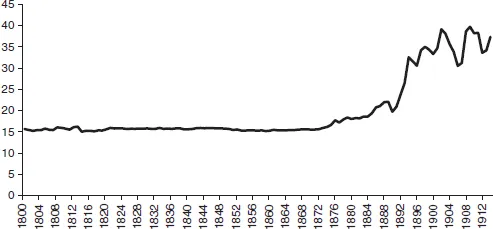

Discoveries of substantial gold reserves in South Africa, Australia and the west coast of North America from the 1850s increased the availability of the metal, and the relative price of silver became more unstable. Debate raged in Europe and the Americas during the last quarter of the 19th century over the appropriate metal to use as the foundation of the international monetary system (see, for example, Gibbs and Grenfell 1888). Those with large silver reserves and silver coin circulation were unwilling to abandon that metal, and the discovery of huge reserves of silver in the western US state of Nevada in 1859 prompted the USA to encourage the global use of the silver standard – but it was not to be. From the 1870s, more countries moved to the gold standard, and soon network externalities and the falling price of silver encouraged others to follow. However, the demonetization of silver seemed to some observers to be a contributing factor in the deflation and economic depression of international commerce in the 1880s and 1890s. A last-ditch effort by the US Congress led to an international conference in Paris to reconsider the potential for bimetallism in the summer of 1878. By this time the tide seemed to have fully turned toward the gold standard, although there is still debate over whether the dominance of gold was completely inevitable (Oppers 1996, pp. 143–62; Flandreau 1996, pp. 862–97; Meissner 2005, pp. 385–406). In 1872 Germany demonetized silver, followed a year later by the USA. Also in 1873, France limited silver coinage to try to combat Gresham’s Law, and gradually moved to the gold standard. After 1900, the only major countries on the silver standard were relatively low-income countries like China and Mexico. Figure 1.2 shows that the adoption of the gold standard from the 1870s was accompanied by a rise in the ratio of ounces of silver to ounces of gold from about 15:1 to almost 40:1 by 1900.

The four decades from 1870 are usually considered the era of the classical gold standard, when most countries defined their currencies in terms of a value of gold, gold circulated as coin, and there was a free movement of gold between countries. The gold standard facilitated the operation of the international monetary system by encouraging stable exchange rates and linking the money supply and prices to an apparently self-correcting system. Under the stylized system described as the Price Specie Flow Mechanism, balance of payments deficits would cause an outflow of gold and a contraction of the money supply. Prices would tend to fall relatively and interest rates to rise, restoring competitiveness. As a result, capital would flow back and the trade balance would improve, thus eliminating the balance of payments deficit (for more detailed accounts of the gold standard see Bordo 1989, pp. 23–113; Eichengreen and Flandreau 1997). In the classic stylized design, the gold standard was a self-correcting system that required little government or central bank intervention and ensured that global imbalances were minimized. In practice, however, the system was not nearly so automatic and required a degree of coordination. Nor was this a period of uninterrupted economic peace; countries on the periphery of the global economy experienced debt crises and financial crises through this period, and the USA experienced a sharp depression in the 1890s. Nevertheless, relatively stable exchange rates underpinned a huge and unprecedented surge in international investment, international migration and international trade that promoted global growth, particularly in economies that received large flows of migrants, capital and technology like the USA, Canada and Argentina. In retrospect, after almost 30 years of conflict, from 1914 to 1945, the Classical Gold Standard era seemed, indeed, to have been a golden age for globalization.

Figure 1.2 Gold/silver price ratio (ounces of silver per ounce of gold)

Source: Officer

Lawrence and Samuel H. Williamson (2011).

The operation of the classic gold standard in which gold circulated as coin was, in the end, relatively short-lived. Already in the 1890s many countries had ‘economized’ on gold by holding sterling or dollars in their reserves instead of gold itself. Then the onset of the First World War in 1914 prompted the suspension of the convertibility of gold and a rebalancing of the global economy. Britain’s economic and commercial dominance had been eroding relative to the rise of the USA and Germany in the 30 years before World War I, but the end of the war marked a sharp shift in economic power toward the USA, as Germany struggled under the economic pressures of defeat. Despite this dramatic change in the architecture of the global economy, there was a strong collective will to return to the era of relative prosperity of the pre-war era. It was assumed that this was predicated on a return to the gold standard.

The restoration of the gold standard was complicated by the increase in the global money supply during the war. National money supplies could no longer be as closely linked to the physical circulation of gold, and most countries demonetized gold by withdrawing it from circulation and outlawing private trade in gold. Rather than backing their currency issue with gold, many countries held sterling or dollars as foreign exchange reserves, so the role of gold was further reduced. These changes were designed to make the system more flexible and robust, but in the end they became the foundation of a dysfunctional international monetary system. In their zeal to return to the ‘golden age’ of the pre-war globalization, many countries adopted inappropriate gold values for their currencies, based more on sentiment and politics than on economic reality. Thus both Italy and the UK returned to the pre-war parity despite the fundamental weakening of their relative economic positions. France undervalued in order to promote balance of payments surpluses – but this undermined price stability by increasing inflationary pressure. Furthermore, the pegged exchange rate system meant that as the US slid into depression in the late 1920s, other countries were drawn down alongside as they sought to stabilize their exchange rate rather than promoting economic growth. The result was that the interwar depression spread through the pegged exchange rate system (Eichengreen 1992; Kindleberger 1986). After years of struggle, the UK abandoned the gold standard in September 1931 and was followed by most other countries in the next tw...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Towards a Global History of Gold

- 1 The Global Gold Market and the International Monetary System

- 2 Gold in Latin America: What the Gold Standard Meant in Brazil and Mexico at the Beginning of the 20th Century

- 3 The Bank of England as the World Gold Market Maker during the Classical Gold Standard Era, 1889–1910

- 4 Gold Refining in London: The End of the Rainbow, 1919–22

- 5 South African Gold at the Heart of the Competition between the Zurich and the London Gold Markets at a Time of Global Regulation, 1945–68

- 6 The Hong Kong Gold Market during the 1960s: Local and Global Effects

- 7 Gold as a Diplomatic Tool: How the Threat of Gold Purchases Worked as Leverage in International Monetary Relations, 1960–68

- 8 Market Status/Status Markets: The London Gold Fixing in the Bretton Woods Era

- Index