eBook - ePub

Showstoppers!

The Surprising Backstage Stories of Broadway's Most Remarkable Songs

This is a test

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Showstoppers! is all about Broadway musicals' most memorable numbers—why they were so effective, how they were created, and why they still resonate. Gerald Nachman has interviewed dozens of iconic musical theater figures to get their inside stories for this book, including Patti LuPone, Chita Rivera, Marvin Hamlisch, Joel Grey, Edie Adams, John Kander, Jerry Herman, Sheldon Harnick, Tommy Tune, Harold Prince, Donna McKechnie, and Andrea McArdle, uncovering priceless previously untold anecdotes and details.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Showstoppers! by Gerald Nachman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

JUST FOR OPENERS

It’s hard to think of a great musical that doesn’t start with a stunning opening number that doesn’t just set the scene but establishes the theme, style, and tone. The opener may make all the difference. It’s the song that says hello, creates a crucial first impression, and, ideally, allows the audience to relax and look forward to a musical that they have paid dearly to see.

An opener is the number that shouts Listen up! and invites us to look forward to all that is about to follow. It tells us: Stop worrying, you’re in good hands. A not-so-great opener can confuse an audience or get a musical off on a leaden left foot. Two not-yet-hit shows—Fiddler on the Roof and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum—were famously in trouble in their first weeks because the openers didn’t do their job. They neglected to communicate what was coming up. The rewritten openers—“Tradition” and “Comedy Tonight”—got each show off to a robust start, set the evening’s agenda, grabbed the audience’s attention, and gave each score just the rollicking shove it needed to send it rolling on to triumph. Both shows might have succeeded anyway, but their rewritten knockout opening numbers put the audience in a receptive state and booted the shows into high gear.

A great opening is an audio preview of coming attractions. A just OK opener puts the audience on alert. Musicals scholar Mark Steyn claims, “What’s wrong with most [bad] musicals can usually be traced to something in the first ten minutes.” Gypsy opens with a bunch of little girls bleating out a banal kiddie song, “May We Entertain You,” in a tacky vaudeville act, but the show is swiftly kickstarted when the stage mother from hell Rose Hovick (Ethel Merman originally), strides down the aisle bellowing, “Sing out, Louise!”—a phrase now firmly embedded in showbiz lore. That moment warns us, Watch out for this woman—she sounds formidable. Rose’s unsung first line is the show’s true opener.

Marvin Hamlisch explained that the opening number in A Chorus Line—“I Hope I Get It”—is as significant as any number in the show. It tells the audience what’s at stake and why they should care. “You need to tell an audience what the show is about.” He pointed to another great near opener, “The Telephone Hour” in Bye Bye Birdie: “It’s not just the music and lyrics—look at that set!” marveled Hamlisch, indicating a stage chocked with teenagers in a honeycomb of cubicles babbling on telephones in their bedrooms. “There are so many things that go into that first song.” Mark Steyn notes, “In a musical, the first number has to be more than just the number which comes first.”

Openers are far more vital now than they used to be, when shows had overtures to help set the mood before the curtain went up. In those days they also had curtains, which have since been abandoned for no discernible reason. Most musicals now open cold, with nothing to help warm up an audience. So the heavy burden of setting the right mood falls entirely on that first number. In the days of overtures and a curtain that masked the opening scene, the audience had a chance to settle back in their seats and get set for something presumably wonderful about to occur. Today’s openers are out there on their own.

Nobody knows just why or when it was determined that musicals don’t need overtures. A few shows still use them, mainly revivals written during the overture era, which often trim them to only two minutes. Were audiences squirming in their seats and growing restless if forced to sit through a four-minute musical teaser? The overture was suddenly regarded as a time-wasting drag, when in fact it’s just the opposite. It provided an opening jolt of electricity that charged up an audience. Big musical movies like Funny Girl (and even nonmusical films, like Doctor Zhivago and Around the World in 80 Days) had overtures, sometimes even intermissions, signifying it was not just a movie but an event. Somehow the overture degenerated into background music for yakkers. Audiences, now used to movies, treat overtures as a kind of live Muzak. Today the overture has been replaced by a utilitarian announcement commanding you to turn off your cell phone and all electronic devices, unwrap your damn candy, take no photos, and basically shape up. Not a welcoming, let alone exciting note to begin on—a totally antitheatrical, mood-destroying moment that has all the charm of an airport terminal announcement.

The overture was invented to provide a melodic, mood-enhancing climate, an emotional transition between opening your program and opening your senses to the show about to start. There are few more thrilling moments in theater than the overture to Gypsy, with that slide whistle and cymbal crash denoting we are about to enter the tinny world of vaudeville, or the drum major’s whistle that leads off the overture to The Music Man—a signal that a marching band may soon be heading your way.

Of course, a great overture sets up such high expectations that it requires an exciting opening number to top it. These days the opener has to do the work of the rudely abandoned overture. Here are a few electrical openers that can make the hair on your arms stand up and perhaps cause your heart to flutter a few beats faster.

GUYS AND DOLLS

“Fugue for Tinhorns”

You could tell Guys and Dolls would be a winning thoroughbred from the first bugle blast of “Fugue for Tinhorns,” maybe the most identifiable opening notes in Broadway history. Its electrifying fanfare calls the horses—and the audience—to the starting gate, and opening-night playgoers were off and grinning at the 46th Street Theatre the night of November 24, 1950.

Instantly, the Frank Loesser song piques your interest, perks up your ears, establishes the scene and characters in slangy racetrack lingo, and alerts you to the musical about to follow. The raffishly attired trio lets us know we’re on foreign but friendly ground—underground Broadway, home to bizarre denizens who look and sound like cartoon characters and yet seem totally authentic. The musical, subtitled “A Fable of Broadway,” is based on tales by Damon Runyon, the street’s most astute and amusing chronicler.

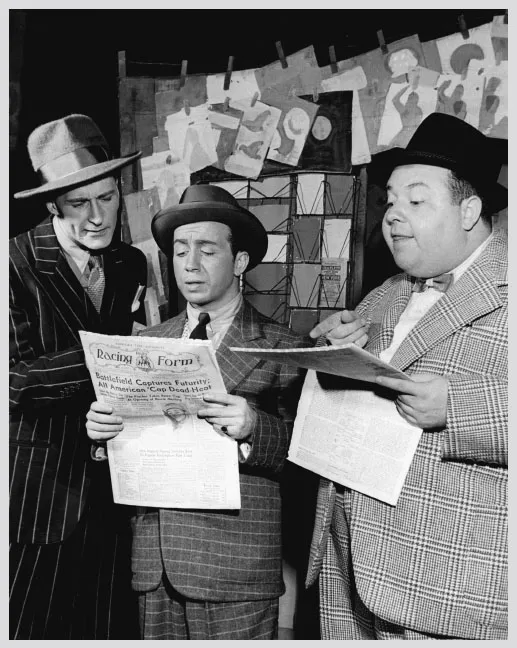

The rousing opener lifts our spirits with a song of overlapping three-part harmony as each guy in the trio, clutching a tip sheet, argues why his horse is the best bet. The charged number’s very first line, sung by gambler Nicely-Nicely Johnson, grabs your ear: “I got the horse right here / The name is Paul Revere, / And here’s a guy that says if the weather’s clear, / Can do, can do”; it’s that Runyonland racetrack speak, “can do, can do,” that tips us to the show’s insider savvy, assuring us we’re on solid turf. Even the wry title, “Fugue for Tinhorns,” alerts us that this is no ordinary musical.

Nicely-Nicely (played first by the beloved and amusing Stubby Kaye; meet him again on YouTube) insists his nag is a sure thing: “I tell you, Paul Revere, now this is no bum steer, / It’s from a handicapper that’s real sincere”; and his pal Benny Southstreet argues, “But look at Epitaph, / He wins by a half, / According to this here in the Telegraph.”

The opener is a roundelay of racing terms, tout chatter, and the nags’ names. In three minutes, we have the setting, the flavor of the show, and the cast of characters. Just concocting a classic fugue for three gamblers is itself a happy, wonderfully innovative touch. We’re rooting them all on before anyone utters a spoken word as the gamblers announce their day’s picks. Even though the show is about craps players, not horse players, it’s clear the show was written by a guy who knew his way around the track.

The original book was written by Jo Swerling, but it didn’t capture Runyon’s ragtag Times Square world, so Loesser called on his pal Abe Burrows, who wrote the hit radio show Duffy’s Tavern, which was peopled with Runyonesque characters. (Trivia note: Burrows’s son James, a chip off the old tavern bar, cocreated Cheers.) By the time Burrows was hired, Loesser had written the entire score, so Burrows had to imagine all the scenes around Loesser’s songs, the exact reverse of how musicals are normally written, which may explain why the scenes so neatly fit the songs that emerge from them.

Racetrack touts, Stubby Kaye at right, declaring their picks in Guys and Dolls.

But in early rehearsals, “Fugue for Tinhorns” was an orphan that didn’t fit in anywhere in the show. Coproducer Ernie Martin had a good idea (occasionally producers have one). “It had nothing to do with the plot,” recalled Martin’s partner Cy Feuer. “We had a great piece of material, and we’re struggling to find a spot for it, and then Ernie finally said, ‘If you’ve got no place to put it, why don’t you stick it up front, as a genre piece, where it’s not about anything but it opens the show and sets the whole thing going?’ Which is where it went and did exactly what Frank [Loesser] thought it would do.”

In Susan Loesser’s biography of her father Frank, Carin Burrows, Abe’s widow, recalled her opening-night memory after “Fugue for Tinhorns”: “There was such a reaction from the audience. That’s when we knew we had an enormous hit. There’s an electricity in the audience that is palpable. You know it right away.” Or to swipe the title of Cy Feuer’s memoir, I got the show right here.

THE MUSIC MAN

“Rock Island”

The hypnotic sing-song opener of The Music Man isn’t even a song; it’s a chant, without music or lyrics that rhyme. “Rock Island” is a 1950s white man’s Middle West rap that breaks out aboard a trainload full of Iowa traveling men in straw hats, chattering about a stranger in their midst about whom they’ve heard dark rumors.

First nighters at the Majestic Theatre on December 19, 1957, who had come to see a new show called The Music Man must have been perplexed by an opening song about a music man without any music. Even more daringly, the opener takes place in a railroad car in which all the men are babbling in some strange dialect. They’re going on about “noggins” and “piggins” and “firkins” that sound like made-up terms, but they’re real items. What the heck is a “hogshead” or a “demijohn”?

After a few bars, though, we catch the drift, but even if we don’t quite absorb every word, the staging of the opening scene is so skilled (originally the work of director Morton DaCosta and choreographer Onna White), and the jiggling salesmen’s chanted conversation is so infectious, that we listen even harder. Early Music Man audiences must have wondered, What sort of weird musical journey are we on exactly?

In fact, the show’s exposition is neatly set up in the men’s babble, which tells us the era, the locale, and the salesmen’s plight; finally, on the very last note, Harold Hill himself is revealed. It’s all disclosed in a few brief bursts of jabber.

Eventually one guy gets down to cases: “Ever met a fella by the name a’f Hill? … He’s a mu-u-sic man. / And he sells clarinets to the kids in the town with the big trombones and the rat-tat-tat drums … with uniforms too, / With the shiny gold braid on the coat and a big red stripe.”

Meredith Willson’s language instantly pulls us back to 1912 Iowa. The archaic phrasing and terminology, the precise period details of the lyric, sets us down in a specific place and time and starts the show with a sense of great authenticity. Wherever we’re headed, we’ve got a reliable guide to take us there. Right off, we’re intrigued, involved, and on our way.

Willson’s bantering song lacks music or rhyme but is hitched to a hypnotic rhythm that mimics the beat of a train chugging through the Iowa cornfields as the salesmen bounce in their seats shouting a call-and-response to the cadence of a clickety-clack railroad rhythm: “CASH for the merchandise,” cries one; “CASH for the buttonhooks,” the other salesmen reply. “Whadayatalk, whadayatalk, whadayatalk.” Critic Walter Kerr called it a “syncopated conversation.” He wrote that the man behind it all, Meredith Willson, “is impatient with dialogue.”

Willson turned dialogue into prose music. When he was the host of CBS Radio’s Sparkle Time (later The Ford Music Room), he wrote pieces in unison for a vocal quartet called the Talking People, as well as a Jell-O commercial in “speak-song,” all warm-ups for The Music Man. Willson used the technique throughout The Music Man, in contrapuntal songs like “Piano Lesson,” which begins with Marian instructing her pupil Amaryllis in dialogue, which is then overlaid with her mother’s hectoring spoken song, “If You Don’t Mind My Saying So.”

As the opening scene develops, chug, chug, chug, chug goes the train as it gathers steam, accompanying the chanting salesmen gripping their sample cases and hanging on to the overhead straps of a herky-jerky locomo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: Tuning Up

- Part I: Just for Openers

- Part II: They Stopped the Show

- Part III: O Say Can You Hear—Broadway Anthems

- Acknowledgments

- Permissions

- Bibliography