This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Updated and revised, the third edition frames strategy as delivering firm value in both the short and long term while maintaining a sustainable competitive advantage. These issues are examined through industry evolution, the rise of the information economy, financial analysis, corporate and quantitative finance, and risk management concepts.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Strategy, Value and Risk by J. Rogers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Evolution of Strategy, Value and Risk

1

Strategy

1.1 Innovation and the entrepreneur

Business cycles as defined in contemporary economics are the recurring levels of economic activity over time. These cycles are described as varying in frequency, size and length, with each stage defined as growth, peak, recession, trough and recovery and each having an influence on inflation, bond yields, short-term interest rates, and commodities. Business cycles were once described, however, as having long predictable durations. Kondratiev waves, named after the Russian economist Nikolai Kondratiev, are long macroeconomic cycles lasting 50 to 60 years that Kondratiev theorized existed in capitalist economies.

One legacy of Kondratiev’s long waves is its influence on Joseph Schumpeter, who formed his theories around long technology waves. In Schumpeter’s theory of business cycles and economic development the circular flow of income, an economic model depicting the circulation of income between consumers and producers, is stationary. Entrepreneurs disturb this equilibrium through innovations, and in doing so create the economic development that drives the economic cycle.

Schumpeter formed two theories in regards to entrepreneurship. The first was that individuals and small firms were more innovative, which he expanded in a second theory in which large firms drive innovation by investing in research and development (R&D) through their access to capital and resources. Schumpeter’s ‘gale of creative destruction’ is the fundamental driver of new industries or industry combinations, the result of entrepreneurs producing innovative new products, processes or business models across markets and industries that either partially or entirely displace inferior innovations. Entrepreneurship can therefore be framed as recognizing, valuing, and seizing opportunities and applies to either individuals, small firms or large institutions.

The term ‘innovation’ was defined by Schumpeter as:

•The commercialization of all new combinations based upon the application of new materials and components, the introduction of new processes, the opening of new markets, and the introduction of new organizational forms (quoted in Jansen, 2000).

Schumpeter also saw a fundamental difference between invention and innovation:

•Invention is the creation of new products and processes that is made possible through the development of new knowledge, or more typically from new combinations or permutations of existing knowledge, while

•Innovation is the initial commercialization of invention, either through the production and marketing of a new product or service, or through the use of a new production method.

Transformations in technology have been driven by momentum from needs and end users in some cases, and developers and system builders in others. The firm, however, has played a consistent role as a participant, and while not always the initiator has been a leading player in innovation as invention and research developed into processes in the 19th century. In the early 20th century many firms had internalized innovation and focused on efficiency and rationalization as a means to secure their technologies. Other firms had leveraged innovation to pursue new products or processes, which became an important development that while riskier was potentially more rewarding.

Over the course of the 20th century, innovation and R&D were institutionalized, which influenced both the trends and speed of change in technology throughout the industrial and industrializing worlds. The principal driver of technology change over the 20th century was the exploitation of science by US industry, which is reflected in the shifts in the research environment. The industrialization of research began with the establishment of centralized research laboratories at the turn of the 19th century at large US industrial and telecom firms. These new science based firms were confronting hostile environments that included new competing technologies for expiring patents and antitrust activities, and these laboratories were established as a defense.

In the period between the first and second world wars US corporate laboratories pushed the limits of innovation strategies. In the 1920s the focus was on optimizing and rationalizing production, which reflected the last phase of scientific management. The 1930s saw the Depression and a shift from engineering departments to corporate laboratories as the principal focus for innovation, with new products being given the utmost priority. This trend laid the foundations for the post World War 2 recovery.

Corporate interest in technology as a driver of development appeared after World War 2 by tying technology investments to strategy. Numerous science-related products emerged from corporate laboratories that were also driven to some extent by huge increases in military spending. This created the linear model of innovation that existed for a number of decades. Persuaded by large World War 2 projects such as the atom bomb and radar, many US firms in the 1950s and 1960s embraced the concept that R&D investment was all that was required for commercial innovation. The linear innovation model reinforced this perception, with the innovation process starting with a scientifically developed concept followed by methodical development stages. The perception was that by basing innovation on science, large payoffs could be expected through the opening of new markets.

Cynicism with this approach began in the US industry during the 1970s and followed soon after in Europe. Up to the 1960s demand from the reconstruction of the industrialized economies and the lack of any major competition resulted in a focus on the optimization and enhancing of system operations as opposed to productivity and innovation. A large component of US R&D was also derived from government funding in the high tech sector, especially the military.

By the 1980s it became obvious in many sectors that an innovation system based on research had problems in executing the later phases of innovation. Another issue was that the expectations of significant new products based on science had been overstated, with final success often elusive. Invention on demand did not fit the process model, with a number of product failures challenging corporate research and management calling into question R&D expenditure levels.

Today open innovation systems have gained attention, with global firms successfully coordinating design and manufacturing communities to deliver their requirements with speed, efficiency and flexibility. Networks have led to successes in innovations and have typically included both small and large firms that swap expertise and information. Innovation prospers on the diversity and flow of information, and therefore having access to knowledge networks has proven to be far more valuable than the centralized corporate laboratory with its long project cycles and large overheads.

1.2 The evolution of industry sectors

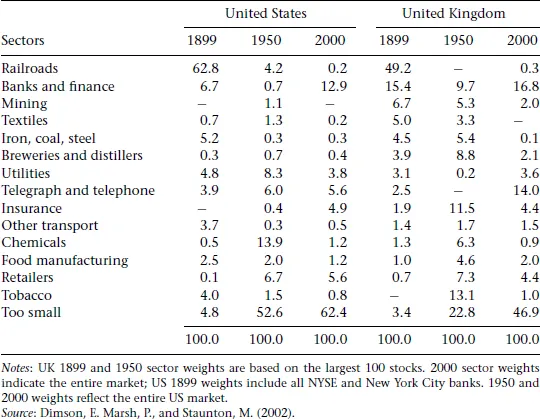

The successive technology waves over the 19th and 20th centuries are reflected in the transformations of the listed stock market industry sectors. Table 1.1 illustrates the industry shifts in the US and UK indexes for the years 1899, 1950 and 2000. The table is based on the industry classifications in use in 1900, with a few additional sectors that although minor in 1900 grew to significance through to 1950.

Railroad companies were the first true industrial giants at the beginning of the 20th century. As they gradually became regulated and nationalized, however, the industry was marginalized by new industries such as steel, chemicals, rubber, mechanical engineering, machinery and consumer durables.

Table 1.1 Industry sector weights based on the 1899 classification system

Another trend is that some sectors that were insignificant in 1900 grew to dominance through to 1950 and then declined by the year 2000. One example is the chemical industry, with US growth increasing from 0.5 to 13.9% in weighting between 1900 and 1950, and then declining to 1.2% by 2000. The UK chemical sector followed a comparable pattern, with a huge weighting increase from 1900 to 1950 followed by a dramatic decline by 2000.

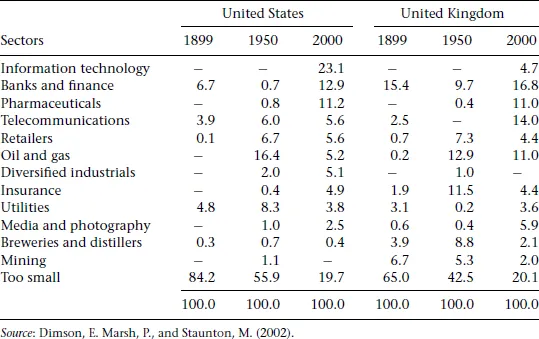

Table 1.2 illustrates the same firms classified under current industry sector definitions and listed according to their US significance. In 2000 the six largest sectors are information technology, banks, pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, retailers, and oil and gas, which combined account for nearly two-thirds of the present-day US market share. Sectors such as oil and gas and pharmaceuticals were nearly nonexistent in 1900, and information technology had a zero weight in the years from 1900 to 1950. In 1950 pharmaceuticals were still relatively insignificant, while oil companies in the US had achieved dominance and then declined in relative weighting. The telecommunications sector while relatively small in 1900 grew to approximately 6% of the US market where it has since remained. The UK telecommunications sector was nationalized up to the 1980s when it was then privatized, ultimately reaching 14% of the UK market.

Table 1.2 Industry sector weights based on the 2001 classification system

The composition of the stock market indexes has always been shifting. Over the first 75 years of the 20th century these shifts were gradual, with new industrials replacing older ones and manufacturing dominating. US industrials, however, began a relative decline after the mid-1950s, with the decline accelerating in the 1970s due to soaring energy costs and increased competition domestically and from overseas. On the supply side US industrials were facing low cost foreign competitors that were producing products that were increasingly improving in quality. On the demand side growth in the US domestic market had ceased, with demand for industrial goods diminishing by the close of the 1960s.

The final quarter of the 20th century saw a significant change in the US economy with the decline in manufacturing and growth in service industries, and most of all a shift to information technology, a revolution that also significantly expanded the extent of services. Table 1.3 illustrates the transformation of the 100 largest US firms as measured by revenues for the years 1955, 1975 and 2000. The 1955 and 1975 lists show a relatively small decline in manufacturing, sales and market value and the rise of financial services, information technology, and pharmaceuticals and health care. Both lists are fundamentally the same, with manufacturing firms dominating. By 2000, however, manufacturing had declined significantly, with financial services, information technology, and telecoms and media dramatically increasing as measured by revenues.

There were a number of fundamental changes in the US economy over the last quarter of the 20th century. The first was the appearance and growth in the components of a new knowledge economy. These included computer hardware, software and services, providers of internet services and content, and the telecoms that develop and manage the infrastructure over which information flows. The combination of these components created an information revolution equivalent to the industrial revolution that generated the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction

- Part I The Evolution of Strategy, Value and Risk

- Part II The Analysis of Performance and Investments

- Part III Quantitative Analytics and Methods

- Index