This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Understand the impact of a global ageing population on how products are bought, and the effect this has on howto market and advertise these products and services to the older generation of consumers. Contains models for companies to evaluate the success of their own strategies, with tools for improving their age-friendly marketing campaigns.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Marketing to the Ageing Consumer by D. Stroud,K. Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Marketing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The ageing consumer – a historic perspective

The importance of older consumers and the techniques employed by marketers to capture their spending power are not new subjects.

As far back as 1991, a front cover of Business Week was devoted to: ‘Those aging Baby Boomers and how to sell to them’. A decade and a half later (2005), Business Week returned to the same subject with another edition and a front cover devoted to the year in which the USA’s Baby Boomers celebrated their 60th birthday.

Twenty years ago, the American academic George P. Moschis published the book Marketing to Older Consumers, followed a decade later by the French marketer Jean-Paul Treguer and his book 50+ Marketing.

The joint author of this book (Dick Stroud) added to the body of knowledge with the publication in 2005 of the marketing textbook The 50-Plus Market.

Virtually all of the hundreds of thousands of words that have been written about older consumers have focused on their behaviour; how they can be segmented, the metrics of their purchasing power and their changing demographics.

Surprisingly, little attention has been given to the universal issue affecting all consumers – how their ageing bodies create marketing challenges and opportunities.

Before discussing the implications of physiological ageing it is worthwhile summarizing what we know (and don’t know) about the marketing factors affecting older consumers. The starting point for this summary is an attempt to resolve the paradox of why such a large group of wealthy people attracts so little attention from the marketing community.

Myths, stereotypes and inertia

Much of the thinking that still permeates the culture of marketing comes from an era when the youth population was growing rapidly. Employment levels were high and expanding the customer base was the number-one priority. This invariably meant focusing on the young rather than the old.

For as long as this subject has been studied, there has been a set of arguments about why it is too difficult or even dangerous to focus overtly on older consumers. These arguments are heard less often but they have not disappeared.

Older people don’t change brands

This argument assumes that once buying preferences are established, during a person’s 20s or 30s, they are difficult and expensive to change. The corollary to this assumption is that by the time a person reaches their 50s their ‘shopping basket for life’ is fixed and hence it is worthwhile spending a disproportionate amount of marketing resources on young people to ‘capture them young’.

Undoubtedly, there is a relationship between brand preferences and age but, as the recent rise in popularity of supermarket own-brands proves, they are far from fixed (in both the USA and Europe). If this argument had any validity, the older population would still be watching their TV using VHS videotape rather than Blu-ray players. This argument means older people would have rejected e-book readers rather than accounting for a third of users in the USA.1

Explicit advertising to the old alienates the young

As with so many of these myths, there is a grain of truth in this argument. Clearly, it would be silly to target a fashion campaign at 20-year-olds showing the clothes modelled by people looking like their parents or grandparents. However, the corollary of this is not that older people should be banished from advertising to avoid alienating their children’s generation.

World-class companies such as Apple and Marks & Spencer have shown that it is possible to create successful advertising that can appeal across the age spectrum. Both companies have run successful advertising campaigns featuring a mix of imagery to appeal to three generations of customers.

We get them anyway

The basis of this argument is that marketing communications that are created to appeal to the 18–35 cohort will also be seen by and influence their parents and grandparents. Why bother to appeal overtly to older consumers when they are already being reached by the primary communications aimed at the young? This is probably the silliest of all of the myths.

If the marketing communications are optimized to appeal to a younger person, then it doesn’t matter how much they are seen by older people – they will instinctively be labelled as ‘not being meant for me’ and ignored. Studies in Asia Pacific, the USA and Europe all conclude that older people believe that many marketing communications are not intended for them – and they are right.

When older people are the largest buyers in many product categories, such as luxury cars, it seems odd to optimize the marketing communications for an age group that can’t afford to buy the product.

Older people are stuck in their ways

This argument assumes that the spirit of change, adventure and experimentation is solely the province of the young. Research conducted by the media agency OMD and Dick Stroud showed that in some European countries (especially France) ageing did result in a loss in the desire to experiment; however, in other countries (especially Australia) the reverse was true. In these countries the desire to try new things increased with age, as did the ability to pay for them.

Older people are technophobic

Again, there is some truth to this argument but the reality is far more complex. A cursory study of the statistics on Internet use shows that nationality, education and socio-economic group are major influencers of online use. In the USA, the richest 18–24-year-olds are 30 per cent more likely to own a smartphone than the poorest. For the 45–54 age group, that difference rises to 230 per cent.2

These myths and stereotypes partially explain marketers’ reluctance to spend the time and budget on older consumers that is warranted by those consumers’ spending power.

Most corporate cultures are resistant to radical change. The pressures to satisfy shareholders each quarter and the short tenure of senior marketing staff, less than 24 months, discourage out-of-the-box thinking and the adoption of new strategies.

There are two other, more important reasons why attitudes have been so slow to change. The very obvious one is the youthfulness of most marketers, especially agency staff. In the UK the average age of agency staff has been approximately 33 years old for the past three years.3 There are no reasons why young marketers cannot excel at understanding and appealing to consumers of their parents’ and grandparents’ generation. This requires skill, determination and above all an unconventional approach. But, the path of least resistance is to approach the market by extrapolating the needs and wants of your peers or basing your insights on the peculiarities of your older relatives.

The final and by far the most important reason why marketers have been so slow to change is the depressingly conservative culture in which they work. This syndrome is best described as: ‘being youth-centric has done us OK for the past decade, so why change now?’

Wally Olins, the co-founder of the branding agency Wolff Olins, is harsher in his use of words:4 ‘Marketers are lazy and will take the easy option. It is much easier to keep doing what you know rather than moving out of your comfort zone.’

Many years ago there was a saying that: ‘Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.’ This was when IBM ruled the computer industry. The reason we are still talking about the aversion that marketers have for older consumers is the assumption that: ‘Nobody ever got fired for targeting the young.’

Trends go on until they stop. In IBM’s case, the business came very close to bankruptcy and with its downfall the old certainties of IT investments disappeared. At some stage, the behaviour of marketers will have to catch up with reality and reflect the importance of the older consumer’s spending power.

What we have learnt

As marketers, we all like to have a complex subject reduced to a list of ‘dos and don’ts’ or a set of ‘the top five things you need to know’. Unfortunately, the subject of marketing to older people doesn’t lend itself to this type of simplistic summary.

During the past decade, our knowledge of older people has improved, as has our portfolio of useful marketing techniques. The following are the most important elements of knowledge that we can use with confidence.

Demographics

Most regions of the world have a wealth of data about the age and geographic profile of all their citizens. The UN is one of the best sources of this information.5 We know that in nearly all regions the median age is increasing; the only differences are the starting point and the rate of change. Allied to this is our understanding of the declining birth rate in most countries. The relationship between these two factors results in one of the most significant social and economic upheavals affecting the planet.

Wealth

In the USA and most of Europe (and many countries of the Asia-Pacific) older people own the largest percentage of wealth. This is not surprising because the components of wealth are residential property and pension investments. Both of these are financial instruments that increase in value with age. There are many marketing opportunities resulting from the conversion of this wealth into income to support older people in their retirement.

Lack of uniformity

Whichever prism you use to view older consumers (for example, economic, social, educational, technological literacy) there is little consistency in their behaviours and personal circumstances. The wealthy, healthy and well-educated 65-year-old professional lady has very little in common with the poor and unemployed manual worker with failing health. Age is a poor proxy for predicting behaviour.

Unreadiness for retirement

Very few governments are adequately prepared to manage the fiscal and social changes resulting from the ageing of their populations. A recent report from the OECD concluded that: ‘The demographic transition – to fewer babies and longer lives – took a century in Europe and North America. In Asia, this transition will often occur in a single generation.’6 Like their governments, most citizens, approaching retirement, are financially unprepared to maintain their quality of life once they leave employment. This situation has been made worse, in Europe and the USA, by the financial effects of the recession.

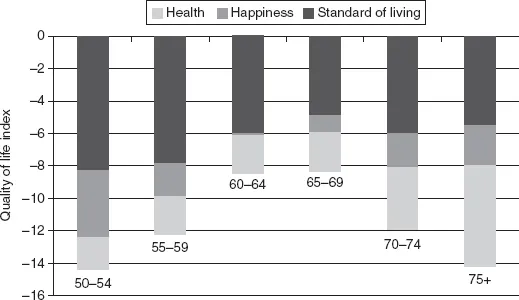

Figure 1.1 shows research from Saga of the perceived change in the quality of life of older people in the UK at the end of 2011, compared with a year ago.7

That the perception of quality of life varies by age illustrates two important points. Not surprisingly, the older the person the more important is their state of health in determining their quality of life. What is not so obvious is that people in the mid- phase of ageing, between 60 and 69 years, feel they have a better quality of life.

Figure 1.1 Annual change in the quality of life index for six age groups

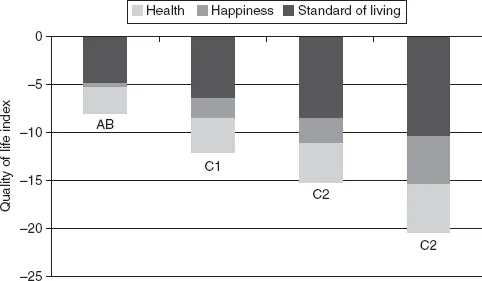

Figure 1.2 Annual change in the quality of life index for four socio-economic groups

People who have retired and secured their pensions are faring far better than those approaching retirement and who are exposed to t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Ageing Consumer – a Historic Perspective

- 2 Population Ageing – Situation Analysis

- 3 Introduction to Physiological Ageing

- 4 Understanding Customer Touchpoints

- 5 The Ageing Senses

- 6 The Ageing Mind

- 7 The Ageing Body

- 8 The Meaning of ‘Age-Friendly’

- 9 Evaluating Age-Friendliness

- 10 Creating an Age-Friendly Strategy

- 11 Age-Friendly Employers and Governments

- 12 The Future

- Notes

- Index