This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

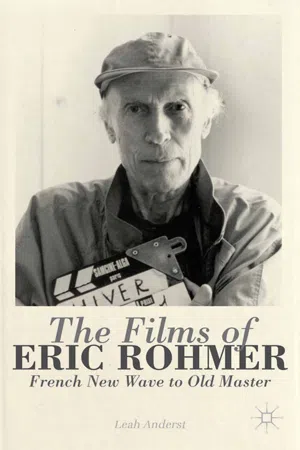

Eric Rohmer was a key figure in French New Wave cinema. Contributors to this volume revisit, complicate, and upend accepted readings and interpretations of perennial Rohmerian topics including the important role of language in his films, the influence of the arts, depictions of gender and class, and the roles played by space and place in his films.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Films of Eric Rohmer by L. Anderst, L. Anderst in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film History & CriticismChapter 1

Eric Rohmer and Me

André Aciman

April 1971. I am 20 years old. My life is about to change. I don’t know it yet. But just a few more steps and something new, like a new wind, a new voice, a new way of thinking and seeing things will course through my life.

It’s a Thursday evening. I have no papers due tomorrow, no reading, no homework. I still have my daily ration of ancient Greek passages to translate, but I can always take care of these on the long subway ride to school. This, I realize, is another one of those very rare, liberating moments when I’ve got nothing hanging over me. I was right to leave work before dark today: it’s a perfect evening for a movie. Tonight, I want to see a French film. I want to hear French spoken. I miss French. I miss France. I would have preferred going to the movies with a girl, but I don’t have a girlfriend. There was someone, or the illusion of someone awhile back, but it never worked out, and then someone else came along, and that didn’t work either. Since then, I’ve grown to hate loneliness and, more than loneliness, the self-loathing it stirs up.

But tonight I am not unhappy. Nor am I in a rush to find a theater. After working all afternoon in a dingy machinery shop in Long Island City (where I was lucky to find a job because my boss is a German-Jewish refugee who likes to hire other displaced Jews), I want to hurry back to Manhattan, not to my home on a dark, sloping 97th Street, where the occasional roadkill reminds me that this modern megalopolis could just as easily be a giant culvert, but to the twilit avenues of Midtown, and the busy luster of their lights. They always remind me of J. Alden Weir’s spellbinding nocturnes of New York or Albert Marquet’s nights in Paris—not the real New York or the real Paris, but the idea of New York and Paris, which is the film, the mirage, the irrealis figment each artist projects onto his city to make it his, to make it more habitable, to fall in love with it each time he paints it, and, by so doing, to let others imagine dwelling in his unreal city.

It is this illusory Manhattan, glazed over the real Manhattan, altered just enough to make me want to love it, that I see now. I like this sudden break from reality, this mini spell of freedom and silence at dusk that lets me feel that I belong in this bright-lit city. Its people going places after work lead exciting lives, and, because I’ve crossed theirs by stepping on the same sidewalks, their bracing vitality has rubbed off on me. There’s something refreshingly grown-up about leaving work without needing to rush home. I like feeling grown-up. This, I suppose, is what adults do when they stop at a bar or sit at a café after work. You find an uncharted moment in the day, and because it’s earmarked for nothing, you allow it to linger and distend and slow things down, till this insignificant moment, normally smuggled between sundown and nighttime becomes something from nothing, and this vague hiatus in the evening finally unfolds into a moment of grace that could stay with you tonight, tomorrow, for the rest of your life—as this moment will, though I don’t know it yet.

* * *

I don’t like going to theaters by myself. Always afraid people might see me, especially if I am alone and they are not. But tonight I feel different. I am not even thinking of myself as a lonely, unwanted, ill-at-ease young man. Tonight I am another 20-year-old with time on his hands, who, on a whim, decides to go to the movies and, seeing he has no one to go with, buys one ticket instead of two. Nothing to it. I’ll sit through this film for 15, 20 minutes. If it doesn’t do it for me, I’ll pick up and leave. Nothing to that either.

I wasn’t even planning to see My Night at Maud’s that night. There had been such a to-do about it, especially after it was nominated a year earlier for best foreign film at the Academy Awards, that I needed to let things die down, put distance between me and what others were all clamoring about. I was intrigued by what I’d read about the film, by the story of the practicing Catholic played by Jean-Louis Trintignant who, owing to a snowstorm, finds himself forced to spend the night in Maud’s home and, despite her disarming looks and unequivocal advances, refuses to have sex with her.

The movie theater on West 57th Street is nearly empty—this is the film’s last run in New York. I hear voices on-screen. I have no sense of how much of the film I’ve missed or if coming late might ruin it. The sudden disappointment of missing the beginning distracts me and gives the entire viewing an unreal, provisional feel, as though seeing it now doesn’t really count, might need to be corrected by a second viewing. I like the option of a second viewing that is already implied in the first, the way I like to see places or hear tales told a second and a third time while I’m still experiencing them the first time—which is how I confront almost everything in life: as a dry run for the real thing to come. I’ll return, but this time with someone I love, and only then will the film matter and be real. This is how I went out on dates, answered job ads, picked my courses, made travel plans, found friends, sought out the new: with enthusiasm, sloth, and a touch of panic and reluctance—the whole occasionally bottled up in a brine of incipient resentment, perhaps disdain. Diffidence as an instance of desire. I withdraw before the real.

I lit a cigarette—in those days you could, and I always sat in the smoking section. I put my coat on the seat next to mine and begin drifting into the movie, because something about the film had already grabbed me. It has as much to do with the film itself as with me, the viewer. The twining of the two—the film and me—was not incidental, but in an uncanny, perhaps untenable way, essential to the film itself, as though who I am matters to the film. Everything happening in my very private life matters to the film. The ferment of lights in Midtown Manhattan suddenly matters, my longing to be in Paris instead of New York matters, the drab machinery shop I’d left behind in Long Island City, the passages I still needed to translate from the Apology, my misgivings about the girl I’d met at a party in Washington Heights more than a year earlier, down to the brand of cigarettes I was smoking and—let’s not forget—the prune Danish I had purchased on the fly to snack on, because something about prunes brings out a sheltered, Old World feel I still associate with my grandmother, who was living in Paris at the time and who loved France and kept summoning me back there because life in France, she’d say, gave every semblance of extending life she’d known before moving there—all these have, like unpaid extras, chipped in and are playing their small part in Eric Rohmer’s film.

The personal lexicon we bring to a film, or the way we misunderstand a novel because our minds drift off a page and fantasize about something superfluous, is our surest and most trusted reason for claiming it a masterpiece. The spontaneous decision to head to the movies tonight is now forever grafted onto My Night at Maud’s. Even walking halfway into the film has cast a strangely premonitory, retrospective meaning to this evening.

* * *

Jean-Louis, the protagonist of My Night at Maud’s, lives alone, likes living alone, though he’ll tell Maud in the film that he wishes to be married. His life has been crowded with many people, many diversions, and women; he welcomes his recent self-imposed reclusion, seemingly putting his personal life on hold to take time out in Ceyrat, near Clermont-Ferrand in the Auvergne, where he works for Michelin. He is not sulking or brooding, just serenely withdrawn. No shame, no loneliness, no depression. This is not Dostoyevsky’s underground man or Kafka’s Joseph K. or, for that matter, yet another jittery, self-hating existential Frenchman. There is something so untormented, so cushy, so restorative in his desire to be left alone that I suspect what makes my own loneliness unbearable by contrast is not so much solitude itself as my failure to overcome it. This might ultimately be the most insidious fiction of the film: the airbrushing of loneliness until it seems entirely voluntary. There is a big difference between Jean-Louis and me. He is not being deprived of company; he can have it any time he wants. I cannot. He could be lying to himself, of course, and he could be wearing a mask and moving in a dollhouse world from which the director had managed to purge all vestige of anxiety and dejection, the way some eighteenth-century comedies ignore the realities of almshouses, suicide, syphilis, and crime. The world Jean-Louis steps into—and this world is made clear enough from the very first shot—is not the stark universe of action-driven films where people hurt, suffer, or die; instead, it is inhabited by a highly rarefied, elitist band of soft-spoken friends trying to figure out the meaning of conventional love with an unconventional mix of profound self-awareness and boundless self-delusion. There is no violence here, no poverty, no disease, no tragedy, no exchange of fluids, not even any abiding love or self-loathing; there are no drugs, no breakdowns, seldom any tears. Everything is whitewashed with irony, tact, and that perennial French gêne, which is the chilling sense of awkwardness and unease we all feel when we’re tempted to cross a line but are held back. Youth shirks off gêne, doesn’t accept it; grown-ups savor it, like an impromptu blush, the undertow of desire, the conscience of sex, a concession to social mores.

Jean-Louis and Maud are adults. They are versed in the affairs of the heart and in the sinuous course desire takes. They do not shun others; but they’re not compelled to seek them either. Rohmer’s men, as I was later to find out from his other Moral Tales, are all on a hiatus from what appear to be thoroughly fulfilling lives. Soon they’ll return to the real world and to their one love awaiting them there. The mini vacation in a villa on the Mediterranean in La Collectionneuse, the return to a family villa in Claire’s Knee, or the adulterous, afternoon fantasy world the husband dreams up in Chloé in the Afternoon—all these are interludes punctuated by women whom the male protagonist already knows he won’t really fall for.

Rohmer’s Moral Tales are nothing less than a series of what may be called unruffled psychological still lives.

* * *

To a 20-year-old, the 34-year-old Jean-Louis seemed old, wise, and thoroughly experienced. He has traveled to several continents, has loved and been loved, doesn’t mind loneliness, indeed, thrives on it. At 20, I had loved one woman only. And I am just that spring beginning to recover. The longing for her, the phone messages she never returned, the missed dates, her snub-nosed I’ve been busy, coupled with her evasive and dissembling I promise I won’t forget, and always my self-reproaches for not daring to tell her everything on the night I stood outside her building staring at her windows, wondering whether I should ring her buzzer, or the night I walked in the rain, because I needed an excuse to be out if she called, which she never did; our perfunctory kissing as we waited for the Broadway Local one evening; the afternoon I spent at her place when she changed her clothes in front of me, but I couldn’t bring myself to hold her because suddenly everything seemed unclear between us; and the afternoon many months later when we sat on her rug and spoke of that time when I’d failed to read her meaning as she took off her clothes, and, even after we had confided all this, I was still unable to bring myself to move, but fribbled our time together with oblique double-talk about an us we both knew was never going to be—all of these, like untold arrows driven into Saint Sebastian, remind me that if I’d never be able to forget loving the wrong girl, I should at least learn not to hate myself for it, because I also know that it is far easier to blame myself for not seizing the moment than to ask what had held me back.

Jean-Louis, like almost all of Rohmer’s men, had already been there and come out on the other side seemingly unscathed. This is the first time that I am even aware of another side. As bashful and tentative as I am, I see that there is still hope for me.

* * *

Early on we meet Jean-Louis in church. He is a devout Catholic. He is eyeing an attractive blond named Françoise. He has clearly never spoken to her before, but by the end of the sermon he decides that one day this woman will be his wife.

Nothing could sound more prescient or more deluded. But, once again, the braiding of foresight and delusion is typical of Rohmer. One feeds the other. Their collusion is not insignificant. The stars are aligned to our wishes or to what is best for us—but never as we thought.

Outside the church one day, Jean-Louis tries to follow Françoise but eventually loses track of her. A few days later, on the evening of December 21, he suddenly spots her on her motorbike but once again loses sight of her in the narrow, busy, Christmas-decorated streets of Clermont-Ferrand. On the evening of December 23, he is strolling about town in the hope of running into her.

And of course he will run into her. But not just yet.

He will, however, bump into someone else: his friend Vidal, whom he hasn’t seen since their student days. In a café that night, the men begin talking, of all things, about chance encounters and, of all authors, about Pascal, the writer most associated with chance, hasard, and, as chance would still have it, the very author whom Jean-Louis had been reading. Coincidence thrice removed.

These multi-tiered coincidences beguile me and won’t let go of me and keep insisting that a greater design is at work here, as though the convergence of so many coincidences, however farfetched, underwrites the whole film, and that this conversation between the two men about coincidence is merely a prelude, a tuning of the instruments for things to come in the bedroom scene everyone has been talking about. The confluence of three hasards in the film, added to my own hasard in happening to be seeing this and not any other film tonight, plus the creeping realization that there is something uncannily personal each time I apprehend anything occurring on multiple removes; all these don’t just stir me intellectually but in some inexplicable manner ignite an aesthetic, near-erotic charge, as if everything in Rohmer has to come back to sex, but only obliquely and ethereally, the way everything about Rohmer has to come back to my life as well, but in an oblique and ethereal manner, because multiple removes keep reminding me that I too like lifting the veil and looking under things, denuding one alleged truth after the other, layer after layer, deceit after deceit, because unless something wears a veil, I will not see it, because unless something is partially derealized, it cannot be real, because what I loved above everything else is not necessarily the truth, but its surrogate, insight, because unlike truth, insight comes from me—insight into people, into things, into the machinery of life itself—because insight goes after the deeper, hidden truth, because insight is insidious and steals into the soul of things, because I myself was made of multiple removes and had more slippages than a mere, straightforward presence, because I liked to see that the world was made in my own image, in shifty layers that flirt and then give you the slip, that ask to be excavated but never hold still, because I and Rohmer and his characters are like drifters with many forwarding addresses but never a home, many selves folded together—selves we’d sloughed off, some we couldn’t outgrow, others we still longed to be—but never one identifiable identity.

* * *

So here are the two men: I am here, says one, and you are there, says the other, and between us there’s time, space, and a strange design, which, to some is no design at all but to us, proof we’re onto something whose meaning nevertheless eludes us.

It is the search and the possible discovery of an undisclosed design in their lives that suddenly enchants me, because everything in Rohmer is abou...

Table of contents

- Cover

- The Films of Eric Rohmer

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Eric Rohmer and Me

- PART I: Rohmer: Critic and Philosopher

- PART II: Narration, Frames, Genres

- PART III: Politics, Gender, and Class

- PART IV: Architecture, Places, and Space

- PART V: Adapting History and Literature

- Notes on Contributors

- Index