This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Transnational Higher Education in the Asian Context

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book offers new insights and perspectives on internationalization and trans-national higher education (TNHE) with contributions from three continents. These include the student experience in Malaysia, China, Japan and India as well as institutional perspectives and pedagogical implications of new research.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Transnational Higher Education in the Asian Context by Tricia Coverdale-Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Didattica & Istruzione superiore. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

DidatticaSubtopic

Istruzione superiorePart I

Institutional Issues and National Contexts

1

Japanese University Leaders’ Perceptions of Internationalisation: The Role of Government in Review and Support

Approaches for internationalisation review and challenges for Japan

There are various approaches to the review of university internationalisation. At the global level, the International Association of Universities (IAU), a non-governmental organisation based at UNESCO, carried out an international survey by asking universities around the world about their priorities and opinions on international activities (Knight, 2006). The IAU survey is highly informative for gleaning trends and differences both at the global and regional levels. However, the results for each country are not published, and the low sample size and response rate for the first survey do not allow for comprehensive analysis on diversified responses within any one country.

As for institutional benchmarking activities, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the Programme on Institutional Management in Higher Education initiated an Internationalisation Quality Review Process (IQRP) and set a guideline for self-review of internationalisation in 1999. In Europe, Johnes and Brown (2007) gave a comprehensive insight on quality issues related to internationalisation of higher education. At the practice level, adding to national-level initiatives seen in Germany (Brandenburg & Federkeil, 2007; Verbund-Materrialien, 2003), the European Centre for Strategic Management of Universities led the benchmarking movement at the regional level. This project was later expanded with other partner organisations to form the European Benchmarking Initiative in Higher Education for enhancing the quality of internationalisation and harmonisation in the European context. At the same time, initiatives for regional-level quality assurance, such as the Bologna Process and the European Quality Assurance Register, have also given Europe a leading position of internationalisation in higher education.

In the USA, the American Council on Education (ACE) is well known for publishing its guidelines, titled Internationalizing the Campus: A User’s Guide. This is based on the IQRP and modified to fit into the US context. ACE stated that the internationalisation of campus largely depends on student involvement because it deals with curriculum and the culture of campus (ACE, 2005). In recent years, ACE has published several documents for international higher education practitioners to assess student learning outcomes for review. This has been accompanied by an increasing demand for information on study abroad programmes and the learning outcomes of those who have studied overseas. With regard to effective practices for campus internationalisation in the USA, the Association of International Educators presents the Senator Paul Simon Award for Campus Internationalisation to USA higher education institutions.

In East Asia, and as already seen in Japan, “internationalisation” tends to be regarded as an issue of “global competitiveness” in research and human resource development. In Korea, the Korean Educational Development Institute, a governmental institute, conducted a survey on the internationalisation of universities as a preliminary survey for implementing internationalisation policies in higher education (Kim, 2008). There, information on the implementation of various international activities is solicited in a standard format, so that the government can learn the degree of the progress of internationalisation in higher education. In China, various governmental projects for fostering world-class universities are ongoing (Liu, 2007; Ma, 2007).

Thus, universities set up their own indicators for assessing internationalisation in establishing strategic approaches to achieve global prestige. Taiwan has also become actively involved at the national level in efforts to realise world-class status. The Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan has issued world rankings of scientific papers for universities (Hou, 2007).

When we examine various approaches in other countries and regions, it can be said that internationalisation review is actively utilised for enhancing transparency and accountability in education. This is also enhanced not only by global initiatives such as the ICT and economic globalisation and competition, but also by pressure region-wide or nationwide in the form of public funding constraints and, in Europe, harmonisation for regional co-operation in education.

It is interesting to note that each case study indicates that internationalisation reviews are implemented without a clear-cut definition of internationalisation in its educational or national context. In this regard, de Wit (2008) stated that many documents, policy papers, and books refer to “internationalisation” without offering a theoretical or practical definition of the concept. He has repeatedly stressed that a rationale for internationalisation is often presented as its definition. It would therefore seem that a meaningful and workable definition of internationalisation is necessary.

Another finding in global trends is that benchmarking (including good practices for internationalisation) is receiving more attention in review efforts, although it is a new approach in international higher education. This implies that the onus is on universities themselves to design reviews suitable for respective institutional missions. Goodman (2007) suggested that the term internationalisation (or kokusaika in Japanese) could be interpreted differently among different types of stakeholders within a single higher education system. Internationalisation could have various meanings even at the institutional level. As most leading comprehensive universities have multiple functions, the meaning of internationalisation in the context of research activities can be quite different and sometimes inconsistent with that attached to teaching or learning activities or third stream activities such as international co-operation for development aid.

Therefore, trials for assessing the success of higher education internationalisation will face the challenge to arrive at a meaningful definition as to what internationalised means and legitimate means of comparison within and among institutions and programmes with different missions. For international review, we need a more comprehensive focus, one that considers input and output and educational exchange as well as excellence in research. Diversified approaches in other countries or regions pose a challenge to Japan to develop a comprehensive review for internationalisation including assessments of the quality of student learning as well as research performance.

The Japanese government basically recognises this imperative, as is reflected in an excerpt from the Council for Asian Gateway Initiative (2007) report:

However, it should be noted that university internationalisation is a multi-layered concept consisting of such diverse ideas as enhancing international exchanges of students and faculty members, making the campus a multilingual and multinational community, providing double degree programs, conducting and participating in international joint research projects, establishing and operating overseas offices, and improving international recognition and reputation. Therefore, internationalisation is not something that all universities should pursue in unison, but something that each university should address voluntarily, based on its characteristics. (p. 16)

The report also advocated improvement in “the self-evaluation and third-party evaluation of the degree of university internationalisation” by the advancement of internationalisation review methods “so that universities can internationalise themselves through a voluntary self-improvement process” (p. 17). It is therefore useful to consider the actual perspectives of internationalisation among leaders of different types of Japanese higher education institutions before arriving at effective approaches in assessing the status of their internationalisation.

Japanese university leaders’ perspectives of internationalisation

Overview of the survey

To grasp the diversity of Japanese university leaders’ perspectives of internationalisation and to find a desirable approach to assess their “international” status, the authors re-examined data from a questionnaire survey conducted by Tohoku University in 2007–2008 (Tohoku University, 2008).

In 2007–2008, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan commissioned reviews to clarify current contexts and identify realistic visions on the review of internationalisation of Japanese universities. As a part of this project, a questionnaire survey on the current status and future vision of the review of internationalisation in higher education was implemented. The purpose of the survey was not to assess universities with any standardised set of indicators, but to comprehend the social context in which respective universities define their goals and implement and assess internationalisation. The main foci were as follows: (a) the definitions and perspectives of internationalisation used by respective institutions, (b) the means by which goals for internationalisation are established, (c) the types of international activities being implemented and (d) the future visions and opinions of internationalisation held by universities.

The questionnaire was sent to all 756 (87 national, 89 local public, 580 private) four-year universities in Japan at the end of December 2007 by postal delivery services and was collected by postal mailings, emails and electronic facsimiles. The questionnaire was sent to the offices of university presidents and was requested to be directed to the persons responsible (e.g. vice-presidents) for international affairs. By the end of March 2007, 624 (77 national, 70 local public, 477 private) institutions responded to the questionnaire, for a response rate of 82.5 per cent. Considering the rather official characteristics of this survey and the fact that the respondents were those who are leading international activities on behalf of their institutions (whose names were revealed in the survey), some positive bias in responses should be assumed.

As has already been established, the structure and dynamics of internationalisation are highly diverse. Institutional characteristics and behaviours are, for the most part, different between public (national and local) and private institutions. It is difficult to comprehend the whole perspectives of internationalisation of higher education in such a stratified higher education system as exists in Japan without setting proper categorisations for higher education institutions. In this article, the authors focus on the comparison of national and private institutions.

Setting goals and strategies

When endeavouring to review the internationalisation of higher education institutions, a clear mission and concrete goals should be set beforehand. In the case of Japanese universities, although the majority sets goals for internationalisation, this appears to be a relatively new phenomenon, partly pushed by governmental initiatives. Questionnaire results show that 60.1 per cent of universities are setting internationalisation as at least one of their top priorities, with this figure rising to 89.6 per cent at national universities. Around 70 per cent of national and local public universities and about 50 per cent of private universities have set institutional plans, goals, and strategies for internationalisation.

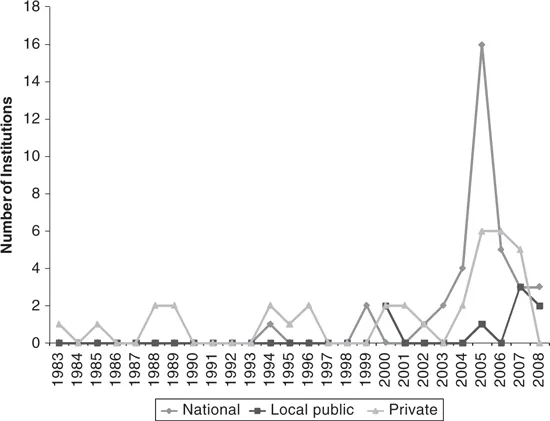

The widespread existence of strategies for internationalisation, especially among national and local public universities, is related to the incorporation of these institutions from 2004 (Figure 1.1). Since this time, all national and most private universities have been required to publish midterm plans and goals, with internationalisation showing to be a fundamental goal in appealing to national and local governments. Although the number is quite limited, some private universities introduced measures more than ten years ago, suggesting that governmental influence through establishing an evaluation system certainly has an impact on the clarification of missions and strategies for internationalisation at the university level.

Figure 1.1 Year the first strategies, plans and goals were established

International positioning as main targets

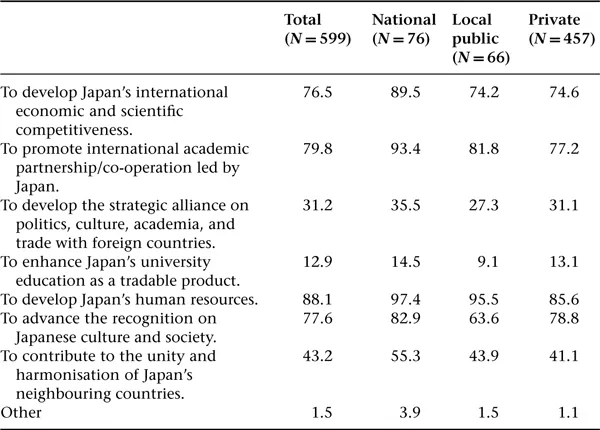

Asked to identify the value of internationalisation for Japanese higher education, nearly 80 per cent of universities responded with “human resource development,” “academic exchange,” “recognition of Japanese culture and society,” and “competitiveness of Japanese science, technology and economy.” These show the consensus that Japanese universities tend to set improvement of international positioning as the main targets for their internationalisation and that the strength of Japanese society lies in research competitiveness, technology and economics and that internationalisation is recognised as a tool to increase competitiveness in these areas (Table 1.1).

Approximately 30 per cent of Japanese universities are aiming to achieve internationally competitive standards in various, specific areas. It is impressive that around 40 per cent of national universities are aiming to achieve “top level” status worldwide and 80 per cent are pursuing internationally competitive standards at least in their research performance (Table 1.2). National universities tend to place more importance on competitiveness in research, a tendency that may be understood with reference to world rankings. About a half of national universities refer to world-class rankings, whereas only 8.7 per cent of private universities cite this as an explicit objective (Table 1.3).

Table 1.1 The value of internationalisation for Japanese higher education (%)

National universities attach greater importance to achieving global excellence in academic quality and performance, whereas local public institutions emphasise social contribution and private universities improvement in the quality of curriculum and teaching and learning.

As for expectations in terms of human resources, national universities tend to set the goal that their students, academic and non-academic staff should be more internationally oriented, whereas local public and private universities tend to expect more in terms of knowledge and understanding of international society.

Considered together, these findings sug...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: The Widening Context of Transnational Higher Education

- Part I: Institutional Issues and National Contexts

- Part II: The Culture of Asian Learners

- Part III: Practical Considerations of the Student Experience

- Part IV: Conclusion

- Index