This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Commonplace Diversity: Social Relations in a Super-Diverse Context

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Drawing on in-depth ethnographic fieldwork, Wessendorf explores life in a super-diverse urban neighbourhood. The book presents a vivid account of the daily doings and social relations among the residents and how they pragmatically negotiate difference in their everyday lives.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Commonplace Diversity: Social Relations in a Super-Diverse Context by Susanne Wessendorf in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Soziologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

SozialwissenschaftenSubtopic

Soziologie1

Introduction: Studying Commonplace Diversity

It is Sunday afternoon and I am sitting in a street café in the centre of Dalston, an area of the London Borough of Hackney. After going for breakfast at one of the many Turkish restaurants just around the corner, I am having a coffee with a couple of friends. The café is run by a Japanese-British couple, and it hosts a variety of music events with artists from around the world. Opposite the café is a Pentecostal church, and as we sit there, the congregation trickles out of the church. There are Caribbean women with beautiful hats and Sunday dresses, followed by African women, some of whom are in traditional African clothes. As they get into their cars, a South Asian Muslim family strolls past, also in their Sunday best, with both mother and daughter wearing beautiful headscarves. Next to the church is a community garden where on this Sunday they are holding a special event. Loud African music is blasting, and Portuguese-speaking Africans are gathering for a Sunday dance which resembles a kind of salsa. None of my friends mentions the collision of these different life-worlds, although they do comment on the remarkable outfits of the churchgoers.

(Research Diary, 5 June 2011)

This book is about the commonplace nature of cultural diversity in a super-diverse urban area, the London Borough of Hackney. Hackney’s diversity is characterized not only by a multiplicity of different ethnic and migrant minorities, but also by differentiation in terms of migration history, educational background, religion, legal status, length of residence and economic background, among ethnic minorities and migrants as well as the white British1 population, many of whom have moved to Hackney from elsewhere. It is estimated that 39.1% of Hackney’s total population was born abroad (Hackney Council, 2013a), its school children speak 95 different languages and there are 27 national groups made up of more than 100 members, ranging from Turkey, Nigeria, Bangladesh, China and Somalia among the larger groups, to Greece, Angola, Germany, the Philippines and Sri Lanka among the smaller ones (Mayhew et al., 2011). These groups are heterogeneous both in terms of their members’ socio-economic, educational and sometimes ethnic backgrounds, and with regard to their migration history, legal status and religious backgrounds.

This ‘diversification of diversity’ (Hollinger, 1995), which characterizes an increasing number of urban areas across the world, is what Vertovec defines as ‘super-diversity’ (Vertovec, 2007a). Super-diversity is here understood not as an analytical device, but as a lens to describe an exceptional demographic situation characterized by the multiplication of social categories within specific localities. These new conditions of super-diversity challenge conventional notions of multiculturalism and its criticism (cf. Vertovec and Wessendorf, 2010) and ask for a new approach to analysing societal contexts characterized by an unprecedented proliferation of social and cultural categories. How has the diversification of diversity impacted on social life on the local level? How do people deal with this new social reality? How do people get along in a context where almost everybody comes from elsewhere? What shapes people’s perceptions about each other? These are the core questions which this book addresses. While this book pays particular attention to cultural and immigration-related diversity, it also draws attention to the importance of categories such as social class, educational background and generation in how people relate to each other.

As I describe in the following section, Hackney has a long history of immigration which, by the beginning of the twenty-first century, has resulted in an exceptional situation of ‘diversified diversity’, with no minority group dominating and large differentiations within groups. This exceptional demographic situation stands in disjuncture to Hackney’s residents’ own perceptions of diversity, especially in regard to cultural diversity. Rather than seeing cultural diversity as something particularly special, it forms part of their everyday lived reality and is not perceived as unusual. This normalcy of diversity is what I conceptualize as commonplace diversity. Commonplace diversity does not mean that Hackney’s residents are not aware of the diversity of the people around them, but they do not think that it is something particularly unusual. Diversity has become habitual and part of the everyday human landscape.

Sennett (2010:269) describes how ‘during the course of an ordinary walk in New York’ the experience of diversity has become so ordinary that it ‘doesn’t much register’ because ‘it lacks disruptive drama’. The story of this book is about this lack of disruptive drama. Diversity has become commonplace in Hackney because there is an ever-present multitude of differences. Importantly, however, commonplace diversity does not refer to a blasé attitude towards difference described in earlier urban sociology (Simmel, 1995[1903]). People are aware of each other’s differences, but because difference is always present, people have learned how to live with it and, in public space and everyday encounters, it does not change the way people behave with each other. Commonplace diversity thus results from a saturation of difference whenever people step out of their front door. Because difference is ever present, people do not pay much attention to it. In Chapter 3, I conceptualize the notion of commonplace diversity in more detail and illustrate it with ethnographic examples.

Because diversity in Hackney has become commonplace, the story of this book is generally a positive one. Everyday encounters with difference in Hackney are rarely conflictual. Unlike much of the current media and political debate on diversity, which tends to portray diversity as a problem, the assumption of tensions on the grounds of migration-related diversity has no grounds in Hackney. In fact, one of my informants told me how she felt offended when participating in a survey which assumed that Hackney’s diversity led to tensions between its residents. This book’s positive account of diversity does not exclude the existence of tensions and sometimes conflict, as exemplified by the riots discussed in Chapter 8. However, it shows that diversity in Hackney’s public space generally ‘lacks drama’. Because of this lack of tensions, I was confronted with the strange circumstance of doing research about something people did not perceive as an issue of contestation. This not only forced me to look beyond cultural diversity and find out which categories of differentiation do play a role regarding people’s perceptions about each other and their social relations. It also pushed me to examine in a more differentiated way how people in a super-diverse context live together and develop social relations, by focusing on where diversity is commonplace and where it is not. Thus, while the research behind this book was based in a culturally diverse area and the book thus pays particular attention to cultural diversity, other categories of differentiation emerged as highly relevant in the course of the research, especially social class, race and generation. These are especially reflected in Chapter 7 on social milieus and private relations and in Chapter 8 on the riots. Before describing more concretely how I approached the study, I will here give a short account of Hackney’s diversification.

Figure 1.1 Map showing location of Hackney

Hackney and its super-diversity

East London, including Hackney, has traditionally been the arrival destination for many of London’s migrants because of its proximity to the docks (Butler & Hamnett, 2011). Referring to spatial and social mobility of migrants, Butler and Hamnett (2011:59) describe East London as a typical ‘immigrant reception area [ . . . ] from which some migrant groups make moves both upwards and outwards’. Indeed, Hackney has seen a long history of population change which increased in the second half of the twentieth century, but reaches back into the seventeenth century with the arrival of Huguenots from France, followed by Jews in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. While the majority of Jewish immigrants first settled in Whitechapel, just south of Hackney, many of them moved to Hackney and beyond during the early twentieth century as a result of growing prosperity. The largest waves of immigration into Hackney originated from the so-called ‘New Commonwealth’, which included India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and the former British colonies in the Caribbean and Africa. These migrations started in the late 1940s and were characterized by labour migration to build up the booming post-war economy. During that time, there was also a sizeable number of Irish people moving to Hackney (Butler & Hamnett, 2011). From the 1970s, migrants from the New Commonwealth were followed by Turkish, Kurdish and Turkish Cypriot migrants who came to Hackney both as labour migrants and political refugees (Arakelian, 2007). Vietnamese refugees arrived from the late 1970s (Sims, 2007). In the 1990s, an increasing number of refugees arrived from the Horn of Africa, the Balkans and elsewhere (Butler & Hamnett, 2011). In 2006, Hackney had one of the largest refugee and asylum seeker populations in London, estimated to be between 16,000 and 20,000 (Schreiber, 2006).

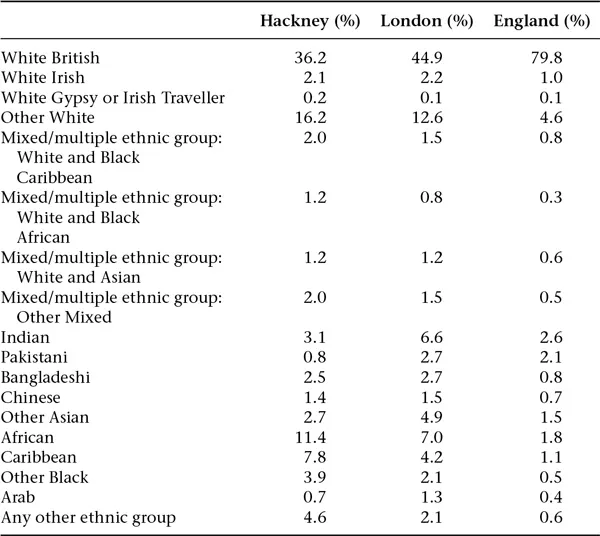

Today, among the biggest ethnic groups in Hackney are White British (36.2%), ‘other white’ (16.2% see below for further details), Africans (11.4%), people of Caribbean background (7.8%), South Asians (6.4%), people from Turkey, Cypress and Kurdish people (5.6%), Chinese (1.4%) and ‘other Asian’ (2.7%, many of whom come from Vietnam), Irish (2.1%), Arab (0.7) and ‘Gypsy’ or Irish Traveller (0.2%) (Hackney Council, 2013b).

These regional groups are comprised of many nationalities. For example, people from the Caribbean originate from a larger variety of islands than in other places in Britain where concentrations of people from one or two islands can be found. Also, Africans in Hackney come from many different countries, with Ghanaians and Nigerians forming the largest groups. But there are also numerous smaller groups from countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Uganda. South Asians are comprised of a majority of Indians (including Gujarati-speaking Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus), Bangladeshis and Pakistanis, the majority of whom are Muslims (http://www.hackney.gov.uk/hackney-the-place-diversity.htm).

Recently, there has been an increase in people from eastern Europe, especially Poland, but also Albania, Romania and Bulgaria (Hackney Council, 2013b).

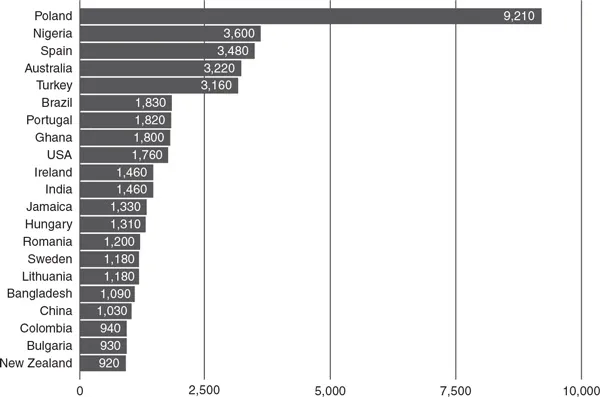

According to the Hackney Cohesion Review, Hackney has the third greatest degree of ethnic diversity, and the fifth greatest degree of religious diversity in England and Wales. This means that ‘it is one of the places in the country where your neighbour is most likely to be of a different background to you’ (Hackney Council, 2010:10). Having a diversity of neighbours also results from little social segregation in the borough, with people being dispersed across the area both in terms of nationality and socio-economic backgrounds (ibid., 2010). At the same time, however, there are areas that are ‘more ethnic’ than others. For example, Turkish, Kurdish and Cypriot businesses dominate two of the main high streets in the borough, and Vietnamese shops dominate another main street. Turkish and Vietnamese migrants set up these businesses during a time when streets like Kingsland Road had become depressed and when there was cheap property available (ibid., 2010). Similarly, along Ridley Road Market, one of the main fruit and vegetable markets in Hackney, there are many African, Caribbean and Asian shops and stalls. While the market was originally dominated by Jewish traders, these African, Caribbean and Asian businesses have slowly taken over since the arrival of these migrants. Meanwhile, those Jewish traders who remained adapted their produce to cater to an increasingly diverse clientele (Hackney Today, 2013; Watson & Studdert, 2006). Other ethnic businesses such as eastern European or Latin American shops can be found across the borough. These shops exemplify a marked increase in people in Hackney identified in the 2011 census as ‘other white’ (16.2% of the population (Hackney Council, 2013b)). This group increased by 60% between 2001 and 2011 (Hackney Council, 2013a), and includes the strictly Orthodox Jewish community (Mayhew et al., 2011) as well as Turkish and Kurdish speakers. The groups which contributed to the increase in the ‘white other’ population, however, mainly originate from eastern Europe, primarily Poland. Other significantly increased national groups include people born in France, Italy and the United States as well as South Americans. The latter now make up 1.7% of the population (Hackney Council, 2013a). For example, 1830 Brazilians and 940 Columbians applied for a National Insurance number between 2002 and 2011. These applications are a good indication of where newcomers have come from (London Borough of Hackney, 2013) (Table 1.2).

Table 1.1 Ethnicity

Note: The Charedi population (estimated at 7.4%, Mayhew et al., 2011) and the Turkish population (6% according to the 2004 Household Survey, London Borough of Hackney, 2004) are often categorized as part of the White British, White Other or Other Ethnic Group category and, for Turkish speakers, sometimes as Arab (London Borough of Hackney, 2013). Source: Census 2011, % of resident population (in: London Borough of Hackney, 2013).

Although, as I describe in Chapter 7, Hackney residents often form close social relations with co-ethnics, there has also been an increasing number of people identifying as ‘mixed’ since 2001. In the 2011 census, 6.4% of the population identified as mixed (white and black Caribbean, white and black African, white and Asian and ‘other mixed’) (Hackney Council, 2013b) and 9.3% of households were formed of mixed ethnic partnerships (Hackney Council, 2013a). Unfortunately, there are no figures available about mixed marriages between different nationalities.

Table 1.2 National Insurance numbers application

National Insurance numbers awarded to foreign nationals in Hackney from 2002–11 by country of origin.

Source: Department for Work and Pensions, March 2012 (in: London Borough of Hackney, 2013).

Source: Department for Work and Pensions, March 2012 (in: London Borough of Hackney, 2013).

Hackney’s national diversity is also reflected in the languages spoken in the borough. Seventy per cent of households in Hackney are English language households, followed by Turkish (4.5%), Polish (1.7%) and Spanish (1.5%). Among the top ten languages spoken in Hackney are also French, Yiddish, Bengali, Portuguese, Gujarati and German (ibid., 2013a). These are just some of the more than 100 languages spoken in the borough (London Borough of Hackney, 2004).

Of Hackney’s population, 38.6% identify as Christian, and there is a variety of denominations ranging from Baptist, Pentecostalist, Adventist to Church of England and Roman Catholics. Fourteen per cent identify as Muslims, again in themselves diverse regarding religious subgroups such as Alevi Kurds and Sunni Turks, and more nationally defined groups. The Jewish population (6.3%) is dominated by the Charedi strictly Orthodox Jewish community, but there are also a number of Jews who do not belong to this community and lead more secular lives. There are also 0.6% Hindus, 0.8% Sikhs and 1.2% Buddhists. The largest groups after the Christians are those who have ‘no religion’ (28.2%) and those who did not state their religion in the 2011 census (9.6%) (Hackney Council, 2013b).

While all these figures and numbers represent the statistical diversity of Hackney, the area’s super-diversity goes beyond ethnic, national, linguistic and religious diversity. The national and ethnic groups mentioned above, as well as the white British population, are diverse in themselves. This applies to educational and socio-economic backgrounds, but also other variables. For example, a Turkish informant of mine told me about divisions between religious and secular Turks within the Turkish ‘community’. Also, there are differences among African migrants not only in terms of their national and ethnic backgrounds, but also the period of migration and their educational backgrounds. For example, many of the Ghanaians and Nigerians who migrated during the 1960s had higher levels of education than those arriving during the 1980s. Similarly, one of my Polish informants told me about differences between longer established eastern European migrants and newcomers, some of whom were less educated than the earlier migrants. One of my Congolese informants also told me about differences, and sometimes tensions, between those of his co-ethnics who had received permanent residency and those who were asylum seekers or refugees. And a Vietnamese informant told me about divisions between Northern Vietnamese and Southern Vietnamese immigrants. Hence, it is not only the sheer number of different national groups that can be found in Hackney, but also their internal diversities in terms of religions, migration histories, educational backgrounds, etc. which makes Hackney super-diverse.

One of the social differences in the borough which has crystallized most clearly in recent years is socio-economic difference which, with increasing gentrification, is the top categorical difference my informants talked about, an issue I discuss in more detail in Chapter 6. Hackney figures among the 10% most deprived areas in the UK, but it is currently seeing the arrival of an increasing number of middle-class professionals, also exemplified by a rise in privately rented accommodation and a growth in residents with the highest level of qualifications, which went up from 32.5% to 42% (Hackney Council, 2013b). Importantly, however, gentrification in Hackney already started in the early 1980s. It represented the continuation of the gentrification of inner-London boroughs which began in the 1960s, with many of the houses in London’s working-class quarters being taken over by middle-class people once their leases had expired (Glass, 1964). Butler describes how gentrification has often been blamed for ‘the displacement of existing lower-class residents and for the abandonment of parts of the inner city with houses lying empty often for years while they await redevelopment’ (Butler, 1996:82). However, the immigration of middle-class people into Hackney during the 1980s did not cause the abandonment of these buildings. Rather, there had been a loss of population in Hackney since 1971, declining by 26% between 1971 and 1991, with many people moving to the outer London boroughs or other areas of the south-east (ibid., 1996). This decline in the population led to the abandonment of numerous properties. Some of my informants who moved into the area during this time told me how the houses they moved into were surrounded by abandoned properties, and how there was a sense of general decay during this period.

The decline in the borough’s population during the 1970s and 1980s could also be an underlying reason why successive waves of immigration into Hackney did not lead to tensions. For example, Turkish and Vietnamese immigrants during this time contributed to the revitalization of Kingsland Road when they took over businesses and shops (Hackney Council, 2010). As I describe in Chapter 6, current gentrification has taken on a different scale and forms part of one of the main population changes in recent years. Rather than cultural diversity, it is this socio-economic diversification and the newly visible socio-economic differences which are most noticed by local residents when asked about population change. The new people moving into the area are most often described as ‘the professionals’. While this term does not account for the diversity which exists within this ‘group’, the term exemplifies more generally the ways in which Hackney’s residents make sense of the different population groups by way of describing them with simple categories, most often relating to class, ethnicity, nationality and race. In the following section, I will briefly discuss the difficulties which can arise from an analytical point of view when using such categories in academic writing.

How to write about ‘groups’?

Throughout this book, I use terms such as ‘Turkish speakers’ or ‘Nigerians’ to refer to people of specific origins. I am aware that studies of migration and diversity always risk taking cultural differences as a given and overlooking the fluidity of cultural boundaries. Such essentialist approaches have also been criticized in regard to studies on multiculturalism...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction: Studying Commonplace Diversity

- 2. From Multiculturalism to Diversity: Mapping the Field

- 3. The Emergence of Commonplace Diversity

- 4. Everyday Encounters in Public Space

- 5. Regular Encounters in the Parochial Realm

- 6. The Ethos of Mixing

- 7. Social Milieus and Friendships

- 8. Commonplace Diversity, Social Divisions and Inequality: Riots in Hackney

- 9. Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index