eBook - ePub

Regional and National Elections in Western Europe

Territoriality of the Vote in Thirteen Countries

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Regional and National Elections in Western Europe

Territoriality of the Vote in Thirteen Countries

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Utilizing both historical and new research data, this book analyzes voting patterns for local and national elections in thirteen west European countries from 1945-2011. The result of rigorous and in-depth country studies, this book challenges the popular second-order model and presents an innovative framework to study regional voting patterns.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Regional and National Elections in Western Europe by R. Dandoy, A. Schakel, R. Dandoy,A. Schakel, R. Dandoy, A. Schakel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Territoriality of the Vote: A Framework for Analysis

1.1. Introduction

Over the last 40 years the institutional landscape in Western Europe has changed considerably. One of the most notable transformations of the state concerns processes of decentralization, federalization and regionalization. This development is well documented by the regional authority index (RAI) developed by Hooghe, Marks and Schakel (2010). For the 13 Western European countries which are the subject of research in this book, they observe that each of them underwent regional reform except for the Swiss cantons and the Faroe Islands. Not only has the authority exercised by regional governments increased but the biggest driver of this growth of regional authority has been the proliferation of elected institutions at the regional level (Marks et al., 2010).

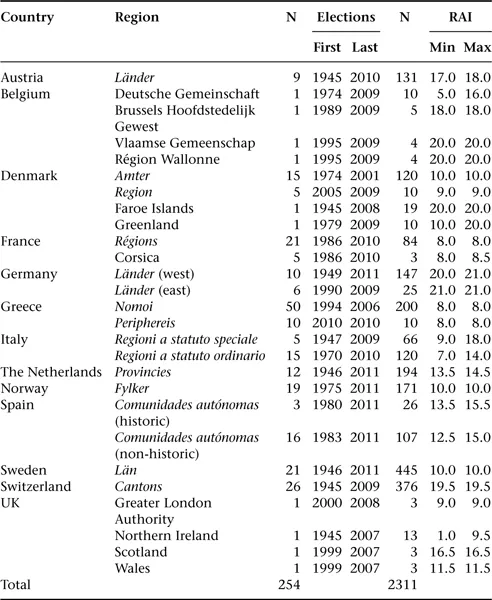

Indeed, regional elections have been introduced in various countries at various times in Western Europe. Following the Second World War, regional elections have been held since 1945 for Austrian and German Länder, the Faroe Islands in Denmark, regioni a statuto speciale in Italy, Dutch provincies, Swedish län, Swiss cantons and Northern Ireland in the UK. Direct elections were introduced in the 1970s in the Deutsche Gemeinschaft in Belgium, Danish amter and Greenland, regioni a statuto ordinario in Italy and Norwegian fylker. During the 1980s, French régions and Spanish comunidades autónomas followed, and in the 1990s, elections were introduced for gemeenschappen and gewesten in Belgium, Greek nomoi, and London, Scotland and Wales in the UK. Clearly, regional elections are on the rise. We now have more regional elections in Western Europe than ever before and their importance has increased significantly as well.

The decentralization processes and introduction of regional elections has not gone unnoticed by political scientists. Most scholars analyzing regional voting behavior are interested in the difference between the national and the regional vote. The starting point of these studies is often the same – namely, the second-order election model (Henderson and McEwen, 2010; Jeffery and Hough, 2001, 2003, 2006, 2009; Tronconi and Roux, 2009). The basic tenet of the second-order election model is that regional elections are subordinate to first-order national elections (Reif and Schmitt, 1980). As a result, fewer voters tend to turn out, and those voters who bother to cast a vote have a tendency to support opposition, small or new parties to the detriment of those parties in national government.

The rank order of elections has recently been contested by quantitative, aggregate studies. Henderson and McEwen (2010) and Schakel and Dandoy (2014) find that the regional turnout is just a bit less than the turnout for national elections for many regions, and in some regions, such as some of the Swiss cantons and small (islands) regions, such as Åland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland and Valle d’Aosta, the regional turnout surpasses the turnout for national elections. In addition, a study of more than 2900 regional elections (Schakel and Jeffery, 2013) shows that the extent to which government parties lose vote share in regional elections varies hugely across regions, and it depends on the amount of authority exercised by the regional government and the extent to which non-statewide parties (NSWPs) participate.

This volume aims to study regional elections whilst avoiding what has been termed by Jeffery and Wincott (2010) ‘methodological nationalism’ – that is, the tendency of political scientists to take the national level as the unit of analysis. This tendency to choose the nation-state as a unit of analysis has been widespread across election research, and has often been an unreflected and uncritical, or ‘naturalized’, choice. As a result, most research on elections and election surveys concerns ‘national’ elections and more, in particular, lower chamber and presidential elections. A consequence of methodological nationalism is that phenomena not manifest or significant at the regional scale of analysis remain ‘hidden from view’ or, as Michael Keating puts it more directly (1998, p.ix), ‘territorial effects have been a constant presence in European politics, but ... too often social scientists have simply not looked for them, or defined them out of existence where they conflicted with successive modernization paradigms’. This is not to say that the nation-state is becoming redundant or rendered insignificant as regional-scale politics becomes more important. The national scale remains the primary focus of most citizens, political parties and interest groups in most areas of political contestation in most advanced democracies. What this collection of country studies aims to achieve is to examine regional elections ‘on their own terms’ instead of taking the ‘prism’ of national-level politics as the natural starting point (Jeffery and Schakel, 2013).

This book presents 13 country studies which analyze regional election results in depth. The countries are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK.1 These are all long-standing democracies with a history of more than five decades of holding free and fair national elections (except for Spain). The selection is worth studying because the countries vary considerably in their experience with regional elections: some have held regional elections for more than 50 years (Austria, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland) while others introduced elections in the 1970s (Denmark and Norway), 1980s (France and Spain) and 1990s (Belgium, Greece and the UK). In addition, some countries introduced regional elections at various times for different territories: Belgium introduced them for the Deutsche Gemeinschaft in 1974, for the Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest in 1989, and for the Vlaamse Gemeenschap and the Région Wallonne in 1995; in Germany, elections for the East German Länder were reinstated in 1990; and in Italy and Spain, elections for regioni a statuto ordinario, respectively, non-historic comunidades autónomas, were introduced at later dates than for regioni a statuto speciale and the historic comunidades autónomas.

Regional elections are held to elect representatives for the regional government and therefore we need to define regional government. It is the government of a coherent territorial entity situated between the local and national levels with a capacity of authoritative decision-making (Hooghe et al., 2010). In more practical terms, Hooghe et al. (2010) include levels of government with an average population greater than 150,000. For the purpose of this volume, we include regional governments which hold direct elections and exclude those with indirect elections or which do not hold them. This decision leaves the vexed issue of multiple regional tiers which hold direct elections in a country. We have decided to focus on the highest regional tier, which in all cases is also the most authoritative regional government. The following subnational elections are excluded: provincial elections in Belgium, Italy and Spain; departmental (canton) elections in France; Kreise elections in Germany; and county elections in the UK. A list of the regional elections analyzed in this book is presented in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Countries, regions and regional elections covered

Notes: RAI=regional authority index score (Hooghe et al., 2010).

We apply a common framework which distinguishes between five dependent variables. Each country chapter will discuss congruence between the regional and national vote, turnout, change in vote shares between regional and national elections, government congruence, and electoral strength for NSWPs. These dependent variables are selected because they are thought to reflect the most important elements of regional voting behavior (see p.18–24). In addition, each of the contributions will discuss a common set of hypotheses in order to be able to derive the most important factors which lead to divergent regional election results.

In addition to a deductive part, the country chapters will employ an inductive research strategy. The contributors of the country studies were asked to assess how far they could identify factors which may impact on regional voting behavior in addition to the set of variables identified in the common framework. In other words, a ‘top-down’ approach is combined with a ‘bottom-up’ line of research. In the Conclusion (Chapter 15) we will make an overall assessment of the various proposed independent variables. We hope that the combination of deductive and inductive elements in the research framework does justice to the appeal of methodological nationalism for studying regional elections on their own terms and, at the same time, acknowledges the valuable work done by scholars who incorporated ‘nationalist’ assumptions in their work.

In the remainder of this Introduction, we proceed in two steps. First, we confront the use of the second-order election model as the dominant framework in regional election research by pointing out conceptual and empirical challenges. Next, we present the analytical framework of this volume, which consists of two parts. The first part focuses on the factors that may impact on regional election behavior and identifies regional institutions and territorial cleavages as two broad categories of independent variables. The second part concentrates on the dependent variable side and introduces congruence of the vote as the main aspect of regional electoral behavior. In order to gain an insight into the causes of dissimilarity in the vote, this framework also includes turnout, vote share changes, government congruence and vote shares for NSWPs as secondary dependent variables. We end by briefly introducing the country studies, and we save the summary and implications of the country chapter findings for the Conclusion.

1.2. Conceptual and empirical challenges for the second-order election model

Perhaps the most often used framework to study regional elections is the second-order election model. The core claim of the second-order election model is that there is a hierarchy in perceived importance of different types of election. National elections are of a first-order nature and all other elections, such as European, subnational, second chamber and by-elections, are subordinate to first-order elections. Because there is ‘less at stake’ in second-order elections, voters are prompted to use their vote to vent their spleen about national-level politics (Reif and Schmitt, 1980). The second-order model echoes earlier work on US Congressional mid-term elections (Miller and Mackie, 1973; Tufte, 1975), and US scholars have labeled these elections ‘barometer’ elections (Anderson and Ward, 1996) or mid-term ‘referendums’ (Simon et al., 1991; Simon, 1989; Carsey and Wright, 1998).

The core assumption underlying the second-order election model is that there is ‘less at stake’ in regional elections, and this leads to three predictions with regard to regional election results:

1. Turnout in regional elections is lower than for national elections.

2. Government parties lose votes.

3. Small, new and opposition parties gain votes.

Because there is generally less at stake in regional than in national elections, voters are inclined not to cast a vote in the former. Voters who do turn out use regional elections to send a signal to the party in statewide office by voting for the party in opposition or voting for new and/or small parties. We argue that the second-order election model may be challenged on a conceptual as well as empirical basis.

If one traces the intellectual roots of the second-order election model, one will stumble upon a developed US scholarship on mid-term Congressional elections (Schakel and Jeffery, 2013). The term ‘second-order election’ was introduced by Reif and Schmitt (1980) to explain patterns observed in the first European Parliament (EP) election. They were inspired by the work of Dinkel (1977) on German Länder elections, who was in turn influenced by the US literature on mid-term elections (Reif, 1997). Elections for the US Congress are held every second year and they coincide with the US presidential elections once every four years. Hence, a mid-term election occurs when an election for Congress is held at mid-term between two presidential elections. The idea is that every election (i.e. including state and local elections) is subordinate to the first-order, presidential election and is used by voters to send a signal to the presidential party. It appears that mid-term Congressional elections produce a systematic loss for the party of the president and only 2 out of a total of 28 mid-term elections between 1900 and 1980 did not produce a loss (Niemi and Fett, 1986). The US literature takes the mid-term loss as a given and tries to explain the magnitude of this loss (e.g. Erikson, 1988; Soberg Sh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- 1. Introduction: Territoriality of the Vote: A Framework for Analysis

- 2. Austria: Regional Elections in the Shadow of National Poltics

- 3. Belgium: Toward a Regionalization of National Elections?

- 4. Denmark: The First Years of Regional Voting after Comprehensive Reform

- 5. France: Regional Elections as ‘Third-Order’ Elections?

- 6. Germany: The Anatomy of Multilevel Voting

- 7. Greece: Five Typical Second-Order Elections despite Significant Electoral Reform

- 8. Italy: Between Growing Incongruence and Region-Specific Dynamics

- 9. The Netherlands: Two Forms of Nationalization of Provincial Elections

- 10. Norway: No Big Deal with Regional Elections?

- 11. Spain: The Persistence of Territorial Cleavages and Centralism of the Popular Party

- 12. Sweden: From Mid-term County Council Elections to Concurrent Elections

- 13. Switzerland: Moving toward a Nationalized Party System

- 14. The UK: Multilevel Elections in an Asymmetrical State

- 15. Conclusion: Regional Elections in Comparative Perspective

- Bibliography

- Index