This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Jocelyne Cesari examines the idea that Islam might threaten the core values of the West through testimonies from Muslims in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and the US. Her book is an unprecedented exploration of Muslim religious and political life based on several years of field work in Europe and in the United States.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Why the West Fears Islam by J. Cesari in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology of Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

MUSLIMS AS THE INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL ENEMY

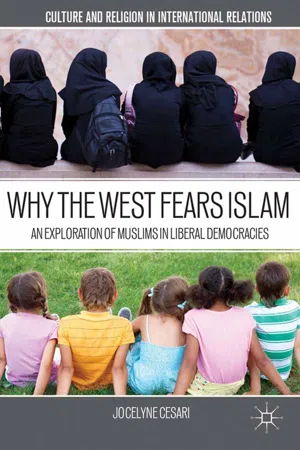

The study of national symbolic boundaries addresses the ways citizens engage in the exclusion of some groups from the national community.1 National community is embedded in institutions and practices that are concerned with the “moral regulation of social life.”2 As such, it includes in traditions, rituals, texts, discourses, and collective memories that reinforce and construct symbolic boundaries around the national community.3 Symbolic codes are the underlying common constituents of these cultural practices that divide the world into those who are “citizens” or “friends” and those who are “enemies.”4 Symbolic boundaries are thereby constructed around the “national community” both internationally and intra-nationally. For example, enemies do not only reside outside of the territorial confines of the nation-state but may also lie within, reflecting the “internal structure of social divisions,” as well as particular national myths, narratives, and traditions.5 It is therefore possible to create a two-dimensional typology of symbolic boundaries within the national community: friends/enemies and internal/external. Through boundary-maintaining processes, social agents are located in one of four cells, which are internal friends, internal enemies, external friends, and external enemies (figure 1.1).6

Figure 1.1 Muslims in the West are seen as both the internal and external enemies

In the case of Muslims in Western Europe, the construction of symbolic boundaries is influenced by several factors: immigrant background, socioeconomic status, and ethnic origin. In this regard, Muslims are at the core of multiple social processes related to the economic changes since the 1970s, as well as the expansion of the European Union and the redefinition of migration flux. In contrast, Muslims in the United States are not as central to socioeconomic evolution or immigration policies because they neither constitute the majority immigrant group nor belong to the lower economic classes. For these reasons, immigration debates have not been Islamicized in the United States.7 Similarly, terrorism remains at the margins of immigration and social concerns. Although, in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing of April 15, 2013, some political actors attempted to explicitly link repression of terrorism with immigration reform, due to the fact that the perpetrators of the bombings entered the United States as political refugees. In Europe, by contrast, the association of Islam and immigration has led to a tightening of immigration laws specifically targeting migrants from Muslim countries. This does not mean, however, that the war on terror has not permeated American immigration policies and increased procedures of control.8

In this regard, the difference with Europe is notable where the categories of “immigrant” and “Muslim” overlap. The reasons for the conflation between Islam and immigration lie in the specific post–World War II history of Muslim presence in Europe.9 Most Muslims are immigrants (and vice versa), or have an immigrant background, and are currently estimated to constitute approximately 5 percent of the European Union’s 425 million inhabitants. There are about 4.5 million Muslims in France, followed by 3 million in Germany, 1.6 million in the United Kingdom, and more than 0.5 million in Italy and the Netherlands. Although other nations have populations of fewer than 500,000 Muslims, smaller countries such as Austria, Sweden, and Belgium have substantial Muslim minorities for their respective sizes. In general, these populations are younger and more fertile than the domestic populations, prompting many journalists and even academics such as Bernard Lewis10 to hypothesize that these numbers will become even more significant in the future.

The majority of Muslims in Europe also comes from three regions in the world, which determines the course of future immigration. The largest ethnic group is Arab, comprising approximately 45 percent of European Muslims, followed by Muslims of Turkish and South Asian descent. The groups are unevenly distributed, based on each European nation’s immigrant history. In France and the United Kingdom, for example, Muslim populations began arriving from former colonies in the middle of the twentieth century, leading to a predominately North African ethnic group in France and a South Asian migrant population in the United Kingdom. In contrast, the Muslim community in Germany began with an influx of mainly Turkish “guest-workers” during the postwar economic boom. Although immigrants currently arrive in Europe from all over the world, the countries with established Muslim populations tend to attract more people from the same ethnic background. Among current European Union member states, only Greece has a significant indigenous population of Muslims, residing primarily in Thrace.

Another feature of European Muslims is their relatively low socioeconomic status.11 As immigrants, the majority of European Muslims came with very low labor skills from underdeveloped nations. This reality, combined with the low standards of education and fewer job opportunities, explains the poor economic performance of immigrant Muslims. Furthermore, across Europe, Muslim immigrant populations are often concentrated in segregated, urban areas, which are plagued with delinquency, crime, and deteriorated living conditions. Additionally, the high density of immigrants from one ethnic group in specific areas raises the question of separatism and ghettoization. In the Netherlands, for example, almost all of its 850,000 Muslims live in the country’s four major cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht, and the Hague, where they make up 30 percent of the population overall.

In the United States, the perception of Islam as the external enemy can be traced back to the Iranian Hostage Crisis (1979–1981) and became more acute after the end of the Cold War and 9/11. Additionally, in the aftermath of 9/11, Muslims have also been seen as internal enemies due to the fear of homegrown terrorism. In Europe, 9/11 and, most significantly, several home grown terrorist attacks such as the Madrid bombings (March 2004) and London bombings (July 2005) have had a far-reaching and multifaceted effect on Muslims. Policies that range from immigration laws to integration, multiculturalism, and State accommodation of Islamic practices have changed in the post-9/11 political terrain.12 The growing fear of home grown terrorism has driven the linkage of security and immigrant integration policies, and this linkage is increasingly connected not only to malevolent outsiders but also to disaffected groups and individuals inside European states.13

As a result, many European intellectuals and public figures have endorsed Samuel Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” to make sense of these social and political challenges. They typically view Europe as a contested continent wherein Western civilization is in conflict with religious fundamentalists bent on eradicating modernization and hard-won freedoms.14 In such a struggle, tolerance and respect for religious differences are considered weaknesses that may be exploited by the enemy. “The intensification of this “civilizational self identification”15 has been exacerbated by the candidacy of Turkey to the European Union, which is seen as an existential threat to European identity.16

The liberal ideology is the vehicle of choice to articulate these “civilizational” concerns, mainly because since World War II the ethno-cultural or “racial” wording has been associated with the Nazi notion of civilizational superiority based on biological differences.17 The demise to a certain extent, of racial and nationalist discourses have, therefore, led to an emphasis on liberal values in defense of national identities. Hence, immigrants who express religious or cultural values that are not part of this liberal narrative cannot be included within the boundaries of the national communities.18

This ideological approach is typical of what Trefidopoulos calls “Schmittian liberalism,”19 which justifies coercive state power to protect the values of liberal societies from illiberal and putatively dangerous groups:

This type of liberalism shares nationalism’s commitment to the defense of the community’s core identity, but differs from traditional nationalism in that the values constituting this identity are liberal and progressive, rather than conservative and traditional. That is, identity liberalism is dedicated to defending the liberal state’s core principles against real and perceived threats from illiberal and perilous immigrants. As such, it is not simply a new brand of old-style xenophobia, but rather a consciously liberal response to the challenges of cultural pluralism that seeks to distinguish itself from its primary competitor: liberal multiculturalism. Schmittian liberals reject liberal multiculturalism because it endorses negotiation, compromise, and a willingness to accommodate groups whose religious beliefs and cultural practices may diverge from those of the majority.20

Consequently, these “Schmittian liberals” frame the problem in existentialist terms and advocate aggressive integrationism to justify policies that might otherwise be seen to contravene liberal principles of toleration and equality.

In this renewed focus on enlightenment, Islam and Muslims make the perfect enemy both inside and outside European nations. Historical reasons make this externalization understandable by a vast majority of citizens because Muslims and Islam have been the typical others of Europe for centuries not only in historical narratives but also in popular culture.21

More specifically, Europe has built its modern political identity in opposition to Islam. In the mirror of enlightened Western elites struggling for equality and democracy, the Ottoman Empire was the other.22

In this sense, Islam is a “topos” that is continuously activated at different moments in European history from colonization to post–World War II immigration. The post-9/11 era adds concerns on pluralization of societies and security, therefore, exacerbating and resurrecting the mentality of an “us versus them” where Muslims are “them.”

Homo Islamicus and His Multiple Embodiments

For several centuries, Islam has played the role of the “other” in the Western psyche. Of course, Muslims have never been the sole “others” of the West: for instance, China, Africa, and aboriginal populations were also constructed in this way.23 Moreover, this construction was not always negative: for example, some forms of Orientalism focusing on eroticism were often favorably contrasted with the puritan West.24

From these multiple facets of the Muslim other, one specific trend emerges: the Western self-definition based on the concepts of progress, nation, rational individual (such as the myth of Robinson Crusoe), and secularization that was built in opposition to Muslim worlds.25 In other words, the liberal modernist story at the heart of Western modern identity has adopted Islam as its foil in order to create itself. Such mirroring can be traced back to the Ottoman Empire’s political domination of Mediterranean lands during the eighteenth century. Europe’s relationship with the Ottoman Empire gradually established the East-West dichotomy that had a decisive impact on the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century world politics. The distinction of East and West was more than a product of religious differences; it was a reflection of political defiance. “The orientalization of the Orient,” as Edward Said deemed it, was the primary effect of a European cultural crisis linked to the advent of modernity, which defined itself against the Ottoman neighbor.26

This binary vision of Islam versus the West has long-lasting effects beyond the formation of European modern polities. For example, this divide has been seen as the primary cause of the post–Cold War international crises. In this sense, the clash of civilizations is a reactivation of the West versus Islam dichotomy.27 The idea of a monolithic Islam, which is at the core of the clash of civilizations, is the same idea (as the pre–Modern Europe self-defining moment) that leads to a reductionism in which conflicts in Sudan, Lebanon, Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan are viewed as stemming collectively and wholly from Islam.28

The construction of Islam and Muslims as the enemy within liberal democracies takes place in this preexisting environment, though with its own specificities related to different domestic polit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Muslims as the Internal and External Enemy

- Part I In Their Own Voices: What It Is to Be a Muslim and a Citizen in the West

- Part II Structural Conditions of the Externalization of Islam

- Conclusion: Naked Public Spheres: Islam within Liberal and Secular Democracies

- Appendix 1 Focus Group Description

- Appendix 2 Focus Group: Moderator Guidelines

- Appendix 3 Draft Survey of the Civic and Political Participation of German Muslims

- Appendix 4 Berlin Survey Description (January 2010)

- Appendix 5 Survey of Surveys

- Appendix 6 Master List of Codes

- Appendix 7 Trends of Formal Political Participation

- Appendix 8 European Representative Bodies of Islam

- Appendix 9 Islamopedia: A Web-Based Resource on Contemporary Islamic Thought

- Appendix 10 Major Wanabi Organizations in Europe

- Appendix 11 Salafis in Europe

- Appendix 12 Fatwas From Salafi Websites

- Appendix 13 Data on Religiosity and Political Participation of Muslims in Europe and the United States

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index