eBook - ePub

The Race for the White House from Reagan to Clinton

Reforming Old Systems, Building New Coalitions

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Race for the White House from Reagan to Clinton

Reforming Old Systems, Building New Coalitions

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Race for the White House from Reagan to Clinton provides a foundation for how the presidential nomination process and the presidential election process have changed over the past three decades by addressing a number of important questions about the nomination and electoral processes.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Race for the White House from Reagan to Clinton by A. Bennett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Historia de NorteaméricaCHAPTER 1

THE MAKING OF THE PROCESS

OF THE 12 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS HELD IN THE PERIOD FROM 1932 through 1976, the Democrats had won 8, the Republicans just 4. Of the 6 presidents elected during this period, only 2 of them were Republicans—Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon—and Nixon had been forced to resign in disgrace. In the 1982 ranking of presidents, all 4 Democrats of this period were in the Great, Near Great, or Above Average categories: Roosevelt at number two; Truman eighth; Kennedy thirteenth; and Johnson tenth. True, Eisenhower was ranked eleventh and Above Average, but Nixon was two from the bottom at thirty-fourth—a Failure.1 In only 3 of these 12 elections had the Republican candidate won more than 50 percent of the popular vote—Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956, and Nixon in 1972. In contrast, the Democrats had averaged 50 percent of the popular vote and 302 electoral votes; the Republicans averaged just 47 percent of the popular vote and a mere 222 electoral votes. This was the background against which our period opens. It was not a promising platform for the Grand Old Party (GOP). But their fortunes were about to change. In the 5 elections that we shall study in the period from 1980 through 1996, the Republicans won 3, averaging 48 percent of the popular vote and 353 electoral votes. The Democrats would win only 2, averaging less than 44 percent of the popular vote and just 184 electoral votes. During these 5 elections, the Republicans received over 50 percent of the vote in 120 state contests; the Democrats in just 30.2

Anyone who has studied American presidential elections during the period 1960 through 1972 will be familiar with the work of Theodore H. White and his series The Making of the President whose four separate volumes covered the elections that fell during that period—the elections of John F. Kennedy in 1960 and Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964 and the elections of 1968 and 1972 that returned Richard M. Nixon. White offered a detailed narrative account of each election, telling its story and explaining to the layman why it turned out as it did. From the 1980s, some noted political scientists began their own series of volumes covering individual elections including Austin Ranney, Gerald Pomper, and Michael Nelson, followed in 1992 by James Ceaser and Andrew Busch, and in 1996 by Larry Sabato. Each of these authors has offered a scholarly analysis of the outcome for an academic audience. The gap in the literature is the book that combines these approaches—the narrative and scholarly—whilst looking at a number of elections. Theodore White got closest to this when in 1982 he published America in Search of Itself: The Making of the President 1956–1980. This volume seeks to pick up where White left off.

But before we study the five presidential elections that occurred from 1980 through 1996, this chapter explains the process for both nominating candidates and electing presidents. Its purpose also is to introduce the terminology of presidential elections—from the Invisible Primary to the Electoral College.

FREQUENCY OF ELECTIONS

Presidential elections are held every four years in years divisible by four. This is required by the constitution in Article II Section 1 and could be changed or varied only by constitutional amendment. Thus whereas Great Britain had no general election during the Second World War—there was no election between 1935 and 1945—the United States continued to hold its elections right through the war years, including a presidential election in 1944. Federal law fixes the election date as the Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Thus the election falls any time between the second and the eighth of that month.

CONSTITUTIONAL REQUIREMENTS

Article II Section 1 also lays down three requirements that a president must fulfill. First, the president must be a natural born citizen of the United States. Some would-be candidates have fallen at this hurdle. When German-born Henry Kissinger once remarked on a TV discussion program that, in his view, to be president these days “you have to be an unemployed, egocentric millionaire,” a fellow panelist remarked drolly, “Yes, Henry, but you also have to be a natural born American citizen.” Austrian-born Arnold Schwarzenegger would also fall at this hurdle.

Second, the constitution states that the president must be at least 35 years old. The youngest elected president of the United States was John F. Kennedy who was 43 when he took office on January 20, 1961. The youngest president was Theodore Roosevelt who was 42 when he became president on September 14, 1901, following the assassination of William McKinley. Our period of study includes Bill Clinton, the third youngest at 46. We shall also include the oldest president—Ronald Reagan, who was less than a month short of 70 when he became president in January 1981. Finally, Article II states that the president must have been resident in the United States for at least 14 years.

Since the passage of the Twenty-Second Amendment in 1951, presidents are now limited to serving only two terms in office. In the period of our study, this applied to Ronald Reagan in 1988. It had earlier applied to Dwight Eisenhower in 1960, and would later apply to Bill Clinton (2000) and George W. Bush (2008). If a president comes to office between elections and serves more than half of the term to which his predecessor was elected, that counts as his first term. If, however, he serves less than half of his predecessor’s term, he would be eligible for election to two full terms in his own right. Thus Gerald Ford who served the last two-and-a-half years of Nixon’s second term would have been eligible for election only once. Lyndon Johnson, however, who served only just over one year of Kennedy’s term was elected in his own right to a full term in 1964 and could have been reelected in 1968.

THE PROCESS OF CANDIDATE SELECTION

The process for choosing presidential candidates has evolved significantly over the past four decades. The most significant raft of changes occurred before 1980—as a result of the McGovern-Fraser Commission set up by the Democratic Party following their debacle in 1968. It was from this set of reforms and others like them that the presidential primary came to prominence. Ordinary voters would now choose national convention delegates and thereby reduce—if not eliminate—the power of the party bosses who had hitherto controlled the conventions, and thereby the choosing of presidential candidates. The process was thereby democratized—surely a good thing.

But not everyone was impressed with the results. Anthony King, looking back on the process that had given Americans the choice between Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan in 1980, wrote of “how not to select presidential candidates.”3 Twelve years later, Robert Loevy wrote of “the flawed path to the presidency—unfairness and inequality in the presidential selection process.”4 In 1996, John Haskell described the process as “fundamentally flawed.”5 We shall consider these and other misgivings in more detail in the final chapter. But first, we need to understand the process—first for selecting presidential candidates.

1. THE INVISIBLE PRIMARY

Writing some 40 years ago, the late David Broder—that doyen of political commentators—stated categorically that “nothing that happens before the first presidential primary has any relevance at all.”6 Nowadays, the nomination process for the party that does not control the White House begins almost immediately after the midterm elections—the ones held exactly two years before the date of the next presidential election. Indeed, in those election cycles when a president has just been elected to his second—and therefore his final—term, speculation about presidential candidates of both parties begins pretty much straight away, four years before the next election. But things were not always done this way. In the run-up to the 1980 election—the first we shall consider in this volume—the eventual Republican nominee, Ronald Reagan, did not declare his candidacy until November 13, 1979, little more than two months before the nomination contest would begin. The first change, therefore, that we will see during this period is the lengthening of what we call “the invisible primary.”

In those election cycles when an incumbent president is running for reelection he will not usually be challenged within his own party, therefore there is nothing happening in his party during this period. We shall see that this was the case for Ronald Reagan in 1984 and Bill Clinton in 1996. But in 1980, Jimmy Carter received a challenge from fellow Democrats senator Edward Kennedy and the Governor of California Edmund “Jerry” Brown. In 1992, George H. W. Bush received a challenge from a fellow Republican, conservative commentator Patrick Buchanan.

The invisible primary is the name given to the period between the first candidate declarations and the voting in the first primaries and caucuses. The term was coined in 1976 by Arthur T. Hadley in his book of the same name.7 Hadley was drawing attention to what was then a new phenomenon in presidential politics, namely that what occurred before the primaries and caucuses was of increasing importance. We shall see that a number of factors have led to the invisible primary becoming longer in duration, but also less invisible. Amongst these factors are the need to raise the increasingly large sums of money required to compete seriously for the presidential nomination of the major parties; the 24/7 news coverage afforded by the rise of the “new media”—cable news channels, talk radio, and the like. During the invisible primary, the prospective candidates spend time campaigning and organizing, especially in the states that will hold the first raft of primaries and caucuses. Over the period that we are studying, four states gradually became established as the early-voting states—Iowa, New Hampshire, Florida, and South Carolina. Without a strong showing in at least one of these early contests, it is very difficult for a candidate to gather any kind of momentum for the long haul through the remaining primaries and caucuses. So it is in these states where much of the early activity occurs.

Then there are other events that have developed during this invisible primary season. For Republicans there is the Ames Straw Poll that occurs in the mid-Iowa town of Ames in the August before election year. The Ames Straw Poll event, which lasts all day, is a cross between a funfair and political fund-raising event. There are barbecues, stalls for any candidates who want to set one up, and a speaking slot given to each candidate who attends. For Democrats, there is the Jefferson Jackson Dinner held in Iowa in November of the preelection year.

As well as debating, campaigning, and organizing, candidates need to spend a good deal of time during this period in fund-raising. This is the fourth important ingredient of this period of the campaign. In addition, because presidential campaigns have become progressively more expensive, the preceding period of fund-raising has gotten longer and longer. Indeed, this is the main reason why candidates have begun their campaigns ever earlier.

For some prospective candidates, all this activity will initially be aimed at increasing their name recognition. If you’re someone like Phil Crane or John Anderson in 1979, then you need to start by getting people to know who you are. It’s all rather reminiscent of the then unknown former peanut farmer and one-term governor of Georgia who in 1975 was going around key states starting every speech with the line: “My name is Jimmy Carter, and I’m running for president.” Of course, some candidates need little or no introduction. If you’re Ronald Reagan in 1979 or Walter Mondale in 1983, then you already have high levels of name recognition. In 1976, Reagan had been runner up to President Ford in the Republican primaries; he had served eight years as governor of California and been a Hollywood movie star. By 1983, Mondale had enjoyed a distinguished career in the Senate and been vice president for four years.

2. THE PRIMARIES AND CAUCUSES

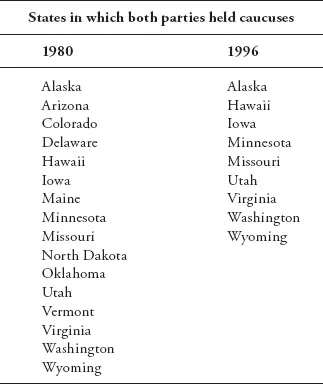

The invisible primary leads directly into the real primaries—and caucuses. Before we consider the calendar, we need to clarify the terminology. A presidential primary is a state-wide election to choose a party’s candidate for the upcoming presidential election. A presidential primary has potentially two functions: first, to show support for a candidate amongst ordinary voters; second, to choose delegates committed to vote for specific candidates at the party’s national convention later in the year. Most primaries fulfill both functions; some fulfill only the former and are therefore referred to as “nonbinding” primaries as no delegates are “bound” to vote for a particular candidate at the upcoming convention as a result of them. These are sometimes called “advisory” or “preferential” primaries: they are merely advisory; they show only voters’ preferences. During the historical period that we are studying, an increasing number of states held a primary but a few—mostly the geographically large but sparsely populated states—still held caucuses. Caucuses are a state-wide series of meetings that last for an hour or two of an evening. So rather than just dropping in to your nearest polling station as in a primary, caucus-goers must attend the whole meeting. Thus it can take hours rather than minutes resulting in much lower turnout. Neither are caucuses a secret ballot: voters usually indicate their candidate preference by a show of hands. As Table 1.1 illustrates, the number of states in which both parties held caucuses declined from 16 in 1980 to just 9 in 1996.

Different types of primaries can be identified by who can vote in them. An “open primary” is one in which any registered voter can vote in either the Republican or Democratic primary. A “closed primary” is one in which only registered Republicans can vote in the Republican primary and only registered Democrats can vote in the Democratic primary. A “modified primary” is one in which registered Republicans can vote only in the Republican primary and registered Democrats can vote only in the Democratic primary, but those registered as independents can vote in either party’s primary.

Table 1.1 States in which both parties held caucuses: 1980 and 1996 compared

Primaries can also be identified by how the delegates are allocated. A “winner-take-all primary” is one in which whoever wins the primary wins all that state’s delegates to the national party convention. These are permitted only in the Republican Party and have declined in use. A “proportional primary” is one in which delegates are awarded in proportion to the vote that each candidate wins in the primary. All Democratic Party primaries are of this type. Most states set a threshold—a minimum percentage of votes a candidate must receive to win any delegates—usually around 10 or 15 percent.

State parties not only decide whether to hold a primary or a caucus, who can vote and how delegates will be allocated, but also when to hold their contest. Over this period there has been a discernable trend to schedule primaries and caucuses earlier in election year and to increasingly group them together at the start of the election calendar in a phenomenon that has been called “front loading.” Iowa traditionally holds the first presidential caucuses and New Hampshire the first presidential primary. Another phenomenon to appear is that of “Super Tuesday.” This occurred as a direct result of front loading. Super Tuesday is a day early in the nomination calendar when a significant number of states—originally from the South—schedule their primaries or caucuses on the same date in an attempt to increase the influence of their region in the candidate selection process.

Voter turnout in primaries and caucuses varies from state to state and from cycle to cycle. The factors that boost voter turnout in these nomination contests are as follows: holding a primary rather than a caucus; having a competitive nomination race; holding the contest early in the cycle before any candidate has reached the requir...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Dediction

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- 1. The Making of the Process

- 2. 1980: “A New Beginning”

- 3. 1984: “It’s Morning Again in America”

- 4. 1988: “Read My Lips: No New Taxes”

- 5. 1992: “It’s the Economy, Stupid!”

- 6. 1996: “A Bridge to the Twenty-First Century”

- 7. Reforming Old Systems, Building New Coalitions

- Appendix A: Presidential Election Results by State: 1980–1996

- Appendix B: States Giving Republican Presidential Candidate More Than 50 Percent of the Vote: 1980–1996

- Appendix C: States Giving Democratic Presidential Candidate More Than 50 Percent of the Vote: 1980–1996

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index