This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing China's Sovereignty in Hong Kong and Taiwan

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Is China always defensive about its sovereignty issues? Does China see sovereignty essentially as 'absolute, ' 'Victorian, ' or 'Westphalian?' Sow Keat Tok suggests that Beijing has a more nuanced and flexible policy towards 'sovereignty' than previously assumed. By comparing China's changing policy towards Taiwan and Hong Kong, the author relates the role of previous conceptions of the world order in China's conception of modern 'sovereignty', thereby uncovers Beijing's deepest concern when dealing with its sovereignty issues.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Managing China's Sovereignty in Hong Kong and Taiwan by S. Tok in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Trade & Tariffs. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Renegotiating China’s Sovereignty in Contemporary Politics

I. The question

Almost all studies on contemporary China’s1 politics and international relations begin with a simple, a priori assumption: that China holds a “Westphalian” view of its own sovereignty (Johnston, 2003, pp. 14–15; also inter alia, Christensen, 1996; Kim, 1998; Robinson, 1998; Fidler, 2003; Johnston, 2003); this view is “absolute” (Ash T. G., 2009) and in policy terms this translates to a staunch and hard-line stance whenever issues of sovereignty are involved in the decision-making process.

How true is this? Should it be treated as a primary assumption, a point where students of international relations begin their analyses when looking into issues related to China?

This book is about questioning this assumption. While it does not go as far as to argue that China displays no sensitivity about its sovereignty, or that Westphalian or absolute views do not exist, it does seek to present a more nuanced understanding of China’s behaviours vis-à-vis its sovereignty issues. Consider these observations on China’s internal dynamics; when looking closer to home, the line “China’s sovereignty is absolute, that of others is relative” becomes increasing blurred.

In Hong Kong, Deng Xiaoping’s suggested formula of “one country, two systems” [yiguo liangzhi] appears to have stood the test of time, and politics, since the Sino-British Joint Declaration was penned in 1984. While Beijing has always insisted that post-handover Hong Kong remains a special administrative region, and that the resulting government is no more than an “administration,” this administration has evolved to capture very different values, encompass a very different legislative/executive structure and operate within an alien legal system different from that in the Mainland. In other words, at the same time that Deng proclaimed that “sovereignty is not a debatable issue” to the British, Deng’s formula voluntarily divides Beijing’s sovereignty between the Mainland and the newly returned special administrative region into a two systems arrangement (Deng, 2008, p. 12). The two systems promise has shown more resilience than sceptics had ever envisioned, and the arrangement has endured the political tensions between Hong Kong and the Mainland in the years that have passed (Kuan, 1999, pp. 23–46; Hsiung, 2000). Through careful management, Beijing has allowed Hong Kong to develop its own brand of politics and sets of institutions that are entirely different from those in the Mainland.

Across the strait in Taiwan, largely owing to the rapidly changing dynamics in the island’s domestic political scene, Beijing’s position(s) on Taiwan affairs remains unclear to many observers. From the ground-breaking 1992 Consensus—that is, “One China with different interpretations”—reached between the late Wang Daohan and late Koo Chen-fu, to the 1995–1996 Taiwan Strait crisis and the rectification of the Anti-secession Law in 2005, China’s view is seen to be shifting constantly between a reconciliatory position and a highly belligerent one. Yet all these occurrences coincided with the gradual opening of China to Taiwan (through xiao santong, or “mini three-links”), and the intensification, in the last decade, of social, economic and political interactions between Beijing and Taipei. Institutionally speaking, two de facto regimes continue to stand against each other across the Taiwan Strait, and again, as in the case of Hong Kong, each embodies different values and systems.

The above descriptions painted a vastly different picture. Should China’s treatment of its sovereignty be absolute, “Victorian,” or “Westphalian” as Ash and many others (inter alia, Segal, 1989; Christensen, 1996; Kim, 1998; Robinson, 1998; Fidler, 2003; Johnston, 2003) have depicted, would one not expect Beijing to be even more uncompromising in its approach towards Hong Kong—and to a lesser extent, Macao—and Taiwan? This is considering that Hong Kong and Macao are symbols of the “century of humiliation” in Chinese memories and blemishes in Chinese nationalistic pride, while Taiwan is long-touted as a “residual” item (Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, 2006, p. 12) in Chinese civil war history and the last obstacle to a so-called united Chinese nation. It is based on this very assumption that Taylor Fravel (2008, p. 265) concludes, “(n)o set of territorial disputes are more significant for China’s leaders than homeland disputes [of Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan] … because of their importance, compromise over these areas is not viewed as a viable policy option.”

But compromises were exactly what had happened, not once, but repeatedly over the course of time. One sees Beijing approaching its own sovereignty issues with utmost intricacy and pragmatism. Maintenance of China’s “sovereignty,” and actualisation of where sovereignty is deemed infringed or in deficit, does not follow a pre-determined path underpinned by Beijing’s definition of where/how its sovereignty lies; rather, Beijing’s attitude has been one that approximates yet another of Deng’s famous dicta: “to feel the stones as one crosses the river” [mozhe shitou guohe].2 There is a huge gap between what was said and what really was practised. Just as Ren Yue (1996, p. 155) describes, “… despite Beijing’s constant claims to uphold the principles of state sovereignty in conducting its foreign [or domestic] policy, discrepancies between China’s declared policy and its contemporary practice are equally obvious.”

While Beijing’s delicate handling of its sovereignty issues can be attributed to many factors, arguably, these policies have to first go through a process of reconciliation, that is, through a filter of internalised norms and/or value order. In other words, Beijing needs to ensure its practices of sovereignty conform to the value system by which it defines itself (Lavine, 1981). It is this view of self and of its sovereignty that this book explores. How can one understand Beijing’s view of its own sovereignty?

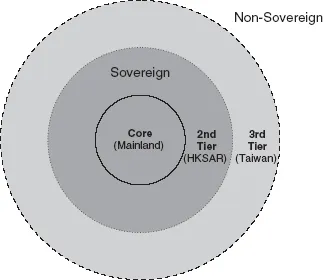

The core argument of this book is that China’s sovereignty, as viewed through Beijing’s lens, is a construct of its historical experiences and political discourses. In this view, the de facto component (right of governance) is effectively detached from the concept. Hence, Beijing’s policy approach towards Hong Kong (and Macao) and Taiwan approximates one grounded on “graded rings of sovereignty.” This approach flexibly accommodates, and at times, voluntarily concedes, a different mix of de facto rights according to each respective context and issue. This view is maintained so long as the idea that a single sovereignty resides in Beijing is not fundamentally challenged. In a similar manner to the late John King Fairbank’s (1968) description in The Chinese World Order, a “cognitive map” (Kirby, 1997, p. 434) of Beijing’s current view of its sovereignty is as follows in Figure 1.1.

The first level is the core, where Beijing’s control is at its strongest; its control then cascades outwards through the second tier to the third, where its control is weakest. Beyond that third tier (non-shaded) are what are known as “external” or “international” relations where Beijing can no longer claim sovereignty. In other words, Chinese authority is neither uniform nor contiguous within its defined boundary, as envisioned by international relations theorists. Policy-wise, although there is a strong impetus to make its authority uniform and contiguous, Beijing has so far refrained from doing so, contrary to common logic. China keeps alive policies such as “one country, two systems,” “shelving sovereignty to pursue joint development” [gezhi zhuquan gongtong kaifa], engaging the international community on Taiwan affairs and so on, thus allowing a large overlap of different levels of authorities between the so-called domestic and international realms.

Figure 1.1 China’s view of sovereignty

The most significant contribution of this book is to add to the theoretical foundation of understanding China as an international player. The findings of this book challenge erstwhile basic assumptions in the study of China and its policy, domestic or foreign. Furthermore, in the discipline of international relations, this work raises important questions about the universality of concepts, ideas, values and norms by exhibiting how China, even when accepting sovereignty as a core principle in international relations, could interpret the very same concept in vastly different manners from its counterparts. Without falling into cultural determinism, in particular avoiding the entrapments of “with Chinese characteristics” theses so passionately forwarded by the “China school” of international relations,3 this book seeks to dissociate from “grand theories” of international relations to highlight the importance of understanding key concepts in context. For example in this case, regarding China’s sovereignty issues, it is most important to examine China’s behaviour under a tinted lens, that is, Beijing’s view of sovereignty, before one can reasonably understand its interests and, possibly, explain its actions.

For these reasons, the arguments presented in this book stand in sharp contrast against a large body of literature (primarily originating from policy analysts in the USA) on China and its policy towards Taiwan and its Special Administrative Regions (SARs). Rather than seeing the Taiwan Strait as a zone of potential conflict (Christensen, 2002; Ross, 2002; Lieberthal, 2005), for example, this author sees even greater potential for management and cooperation between the various parties directly or indirectly involved in the issue. Considering Beijing’s view of sovereignty, as is presented in this book, the glass is certainly half-full, not half-empty. Likewise, naysayers about the abysmal political conditions in Hong Kong and Macao may also have been too pessimistic about Beijing–SAR relations (Chan, M. K., 1997; So, 1997; Vines, 1998). Beijing’s genuine hope to preserve the one country, two systems arrangement opens up a lot of other possibilities in the SARs, were perspectives be shifted to assume Beijing’s point of view. With a different take on Beijing’s view of sovereignty, analysts can go forth on vastly different trajectories in their investigations, and the outlooks are not always bleak.

It is important to stress that this book is absolutely not about taking a position on the sovereignty debates surrounding Taiwan in particular, and Hong Kong and Macao to lesser degrees. There is no intention at all to add to the mix of those politically charged disputes. Neither should any part of this book be lifted out of context to support the arguments of competing camps. This research hopes to make sense of China’s view of its sovereignty and its behaviour regarding these matters. It shall stay this way throughout the whole book.

The referent of this book should also be made clear here. The “Chinese” view presented herein refers specifically to the view extending out from the regime in Mainland China. For this reason, the naming conventions used in this book have been applied solely for the sake of expediency; in no way does this confer any political meanings related to the regimes in China or China’s sovereign issues. In the text, for example, terms like “China,” “Beijing,” “the Chinese Communist Party” (CCP) and the Chinese regime has been somewhat conflated. Likewise, the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan has been given the label “Taiwan” or “Taipei” to aid the flow of writing rather than to take a stand on the legal and political status of the island. Also, Macao/Macau (“Macao” in State Council’s definition, and “Macau” in translations made in the HKSAR), where mentioned, have sometimes been used interchangeably owing to their equally common use in official documentations.

II. Limitation of current international relations studies on Chinese sovereignty

Studies on China have been growing at phenomenal rates since the opening up of the country. However, despite academic interest in China’s sovereignty issues, few efforts were devoted to understanding the Chinese view and behaviours towards the principle considered fundamental to the international system. In his work, Samuel Kim observed that “[o]f all the international norms, state sovereignty is the most basic and deeply internalized principle of Chinese foreign policy,” and acknowledged that “varying degrees of definitions” of the concept do exist “among sovereignty-bound (state) and sovereignty-free (non-state) actors.”4 Unfortunately, China-related researches have not caught on to Kim’s perceptive comment to look into this issue further. Most published works take China’s view of sovereignty very much as a given.

To put things in perspective, as well as make sense of where this book stands in the bigger picture, the literature covering China and its sovereignty can be classified into three categories, according to their level of analysis: systemic, state (from international to domestic or vice versa) and domestic level.

China at the systemic level

This category covers those studies which primarily pivot their analyses on systemic grand theories of international relations. Technically, most of these academic writings do not deal with China per se, but the generic “state” that China encapsulates. Their endeavours thus involve at least the attempts to make cases out of China to support the building of their theories. For most instances, the state—of which sovereignty is one of the constituents—is a given, and sovereignty is relegated to a function of power or interest in international politics.

For the group broadly considered “realists,” sovereignty is a prerequisite to participate in what they deem inter-state politics. Sovereignty, or the lack of it, is what separates states from non-state actors. It is the fundamental principle of international politics, and there is no difference in one sovereignty from another—that is to say, my sovereignty is as “independent,” “equal” and “unanimous” as yours, by the definition of Hans Morgenthau (1985, pp. 331–332).5 Although sovereignty, together with other principles of international relations, offers some form of order in international politics, they are neither the ultimate objectives nor driving forces. For the classical realists, the ultimate driving force is power, as E. H. Carr (2001, pp. 97, 130) had written in his treatise The Twenty Years’ Crisis: “(w)hile politics cannot be satisfactorily defined exclusively in terms of power, it is safe to say that power is always an essential element of politics. International politics are always power politics … ” Morgenthau (1985, p. 5) toed similar lines by assuming that “statesmen think and act in terms of interest defined as power.” For the neorealists, at the minimum, the purpose is to survive the Hobbesian world of “war of all against all,” where life is “nasty, brutish, and short” (Waltz, 1979, p. 103).

Other systemic-level approaches to international politics, from the English school to neoliberal institutionalists, ascribed to similar assumptions. Sovereignty forms a large part of Hedley Bull’s (2002) approach to international relations. Preservation of the internal–external divide, or sovereignty, that separates states is considered one of the four common goals in Bull’s argument for the existence of a society within the international system. Yet again, Bull did not take into consideration how this internal–external constitution could be varied but assumed a society-wide uniformity in its application. The neoliberals, meanwhile, are more interested in explaining why states choose to cooperate than explaining the nuances of sovereignty. In Robert Keohane’s (1984; also Keohane and Nye, 1977) world system of institutionalism and cooperation, for example, states are homogeneously egoists devoid of their internal “self”—they rationally consider “interests,” “costs,” and other factors about cooperating with each other as if their internal constituent does not matter (also Stein, 1990). Sovereignty is again taken as a given without further deliberation, never mind variations in terms of interpretation.

Fixation on the international system and how it works has kept sovereignty out of the picture for the systemic theorists. Even the system-level constructivists, who are known for their more nuanced approach to international relations theories and concepts, have not entirely taken up the challenge of this enterprise. In his seminal work Social Theory of International Politics, Alexander Wendt (2005, pp. 206–214) offered a “textbook” discussion on sovereignty, if only to serve as a water-carrier to develop his theory of how this institution gets internalised by state. Wendt is satisfied with a simple internal–external dichotomy of the concept—not that he is expected to do otherwise in his system-level theorising—and like others mentioned earlier, suffers a Eurocentric (or inaptly-named “universalist”) bias. At this level of analysis, to paraphrase Robert Cox (1986, p. 205), sovereignty remained a singular concept: sovereignty was sovereignty was sovereignty.

China at the state (unit) level

The school most prominent at this level of analysis is that of the neoclassical realists. Developments of the realist school of thought have played down the emphasis on systemic-level analysis and the focus on power so central to the eminent (yet fallible) realist scholars mentioned above. Borne mainly out of a growing discontent over Waltz’s neorealist approach of bracketing out domestic conditions in favour of parsimonious systemic explanation, a new school of realist thinkers turn towards greater appreciation of the internal dynamics of their referents of analysis. Labelling them neoclassical realist thinkers, Gideon Rose (1998, p. 146) describes the group as one that:

… explicitly incorporates both external and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Transliteration

- List of Abbreviations

- 1. Introduction: Renegotiating China’s Sovereignty in Contemporary Politics

- 2. China and the Concept of Sovereignty

- 3. Walking the Walk and Talking the Talk: Sovereignty in China’s Academia

- 4. Imagining One Sovereign: Sovereignty in China’s Political Discourse

- 5. Accommodating Two Governances under One Sovereignty: The HKSAR’s Domestic Spheres and International Space

- 6. Managing Taiwan’s International Space: Comparing Taiwan’s Experiences in the WTO and WHA

- 7. Conclusion: Revisiting the Basic Assumption about China’s Behaviour

- Appendix

- Notes

- References

- Index