This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In most contemporary historical writing the picture of modern life in Habsburg Central Europe is a gloomystory of the failure of rationalism and the rise of protofascist movements. This book tells a different story, focusing on theCzech writers and artists distinguished by their optimistic view of the world in the years before WWI.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Art and Life in Modernist Prague by T. Ort in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Prague 1911: The Cubist City

The Czechs have moved to the forefront of the modernist movement.

—Guillaume Apollinaire, 19141

Among those who interest themselves in modernism in the context of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Prague is sometimes referred to as the “second city of cubism.”2 Paris, it goes without saying, is cubism’s first city and capital, but the style was embraced in Prague with a vigor unmatched in Europe outside of France. In 1911, a group devoted to the defense and promotion of the new art, the Skupina výtvarných umělců or Visual Artists Group, was founded in Prague. Its members wrote extensively about cubism in their journal Umělecký měsíčník [Art Monthly] and elsewhere, sponsored numerous exhibits of the art in Prague, and facilitated the display of Czech cubist experiments abroad. Between 1912 and 1914, the Skupina organized six exhibits of cubism, five in Prague and one at the Berlin gallery Der Sturm. These shows featured the work not only of Skupina members but also of the style’s founders, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, as well as that of other of its pioneers.

The largest exhibit of cubist art in Prague took place in February 1914. Unlike the others, this one was organized not by the Skupina, but by the French poet and critic Alexandre Mercereau at the instigation of Karel and Josef Čapek, who broke away from the group in 1912.3 Reflecting Mercereau’s affiliation with what were known as the Puteaux cubists (i.e., not Picasso and Braque), the show featured the work of Alexander Archipenko, Constantin Brancusi, Robert Delaunay, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Raoul Dufy, Emil-Othon Friesz, Albert Gleizes, Roger de la Fresnaye, Jean Marchand, Louis Marcoussis, Jean Metzinger, Piet Mondrian, Diego Rivera, and Jacques Villon. Czech artists were represented by the painters Josef Čapek, Otakar Kubín, Bohumil Kubišta, Ladislav Šíma, and Václav Špála, and by the architects Josef Chochol and Vlastislav Hofman. It was, according to Mercereau, the largest show of cubist art to date anywhere in the world.4

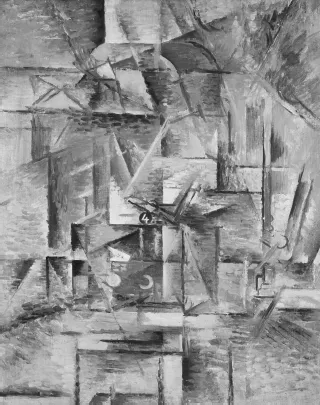

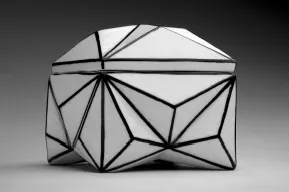

As in France, painting was the most important medium for the Czech cubists (see figures 1.1–1.3), but their most original contributions came in architecture and design (see figures 1.4–1.6). Only in the Bohemian Lands was there a truly sustained effort to articulate cubist ideas in these fields. In the few years between 1911 and the start of the First World War numerous cubist projects were realized in Prague and elsewhere in Bohemia, ranging from private homes to apartment blocks, from commercial buildings to, in one case, a sanatorium. Cubist principles were also applied successfully to the decorative arts, particularly to furniture and ceramics, initiating an imaginative new design tradition. In the years after the war, a style derivative of prewar cubism, rondo-cubism, became something like the national architectural style.

Figure 1.1 Vincenc Beneš, Tram No. 4 (1911). Oil on canvas, 71 x 57.5 cm. Photograph © National Gallery in Prague, 2012.

Figure 1.2 Josef Čapek, The Drinker (1913). Oil on canvas, 75.5 x 50 cm. Courtesy of the Moravian Gallery, Brno.

Figure 1.3 Emil Filla, A Glass and a Bottle (1914). Oil and crushed material on canvas, 30 x 40 cm. Photograph © National Gallery in Prague, 2012.

Figure 1.4 Josef Chochol, apartment house on Neklan Street, Prague (1913–1914). Courtesy of Národní Technické Muzeum (NTM, MAS, AAS Sbírka negativů [Josef Chochol]).

Figure 1.5 Pavel Janák, box with lid (1911). Creamware, ivory glaze, black painted lines. Courtesy of Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

Figure 1.6 Josef Gočár, desk and chair (1915). Polished ash, leather, glass, brass. Courtesy of Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, collection of Dr. Deyl.

There can be no doubt, then, that in the years prior to the First World War, Prague was an important center of cubist art. Although art and architectural historians have done an excellent job tracing the formal basis of the cubist explosion in the Czech context, they have left more or less untouched the question of principal importance to the historian of culture: Why Prague? That is, why exactly did cubism take hold here? Why did it plant such firm roots in this relatively minor, provincial Austrian city? Most importantly in terms of the Austro-Hungarian context, why was there a significant cubist movement in Prague but not in Vienna or Budapest? And why in Prague was cubism overwhelmingly a Czech rather than German phenomenon? To answer these questions means to explain the distinctiveness of Prague’s cultural and social situation at the beginning of the twentieth century. It also means to introduce the artistic generation to which Karel Čapek belonged. Cubism was the movement that first gave direction and coherence to the strivings of Čapek and other young Czech modernists. It was the intellectual and aesthetic starting point of Čapek’s generation.

1911

Generational consciousness frequently arises in relation to disruptive political events such as wars, revolutions, and other crises experienced in the formative years of life, but not always. Whereas in the 1920s and 1930s, the single most important life event for the young men of Karel Čapek’s generation seemed to be the First World War and its immediate consequences—the collapse of Austria-Hungary and the creation of the new Czechoslovak state—they already possessed a powerful sense of generational belonging prior to 1914. But in the prewar years, there was no one political event that shaped this sensibility, no one historical crisis that definitively marked the frontier between the past and the present. As Čapek himself later remarked: “Until the year 1914 there was no world war or revolution; that is, there was no historical schism, conveniently and convincingly dividing history into what had been, the overcome and outdated, and what, victoriously, was yet to come.”5

And yet to the writers and artists of Čapek’s generation the world seemed to be changing immensely and at a pace more rapid than at any time before. They felt that they stood on the threshold of a “new world” shaped by mankind’s ingenuity and creativity in ways previously unforeseen and unimagined. The modern world “blew in from all sides,” recalled Čapek, “even to our provincial backwater.”6 It was made of “machines, concrete, steel”; it possessed “something of the spirit of sport, something American, something exciting and exotic”; it was characterized by “the heedless advance of technical civilization; collective forces, the increase in speed and dynamism.”7 The young artists of his generation were awed by the achievements of modern science and technology, by mankind’s mastery over nature, by the conquest of space and time by speed. They reveled in the new inventions and experiences of modern life and eagerly looked toward the future.

These changes form a crucial part of the background of their generational sensibility, but they do not themselves constitute a rupture. For the young artists of Čapek’s age the break between the past and the present came in the world of art. Their upheaval was the revolution in form and perception undertaken by Picasso and Braque. In a stroke, these painters overthrew the perspectival illusionism reigning in Western art since the Renaissance and liberated the artist from centuries of artistic convention. It was much more than a change in style. It involved, in the words of one historian, “a transformation in the very purpose of art from the interpretation of optically perceived reality to the creation of an aesthetically conceived one.”8 It was this shift that catalyzed their generational sensibility.

Early in 1911 the leading Czech progressive journal of the arts, Volné směry [Open Paths], published an article by the young painter Emil Filla, “The Virtue of Neoprimitivism.”9 It was a bold attack on impressionism in the name of the new artistic style, yet to be labeled “cubism,” then being developed by Picasso, Braque, Derain, and others. It was not well received. Given that impressionism was the style of painting most favored by Volné směry, Filla’s essay was sure to cause a stir, but it was the reproductions it featured, with their unfamiliar distortions of the human form, that raised the greatest storm. The outcry was immediate and almost deafening. Angry letters poured in; readers cancelled their subscriptions; the journal’s printer was so outraged that he refused to extend the magazine any further credit.10 Noisy denunciations of Filla and his supporters at the next general meeting of the Mánes Art Association, the publisher of Volné směry, led to the resignation en masse of the organization’s younger membership and, a few months later, to the establishment of the Skupina výtvarných umělců (see figure 1.7). As Filla later remarked, it was the moment when “the entire young generation left Mánes.”11

The “young generation” that resigned from Mánes included Vincenc Beneš, Vratislav Brunner, Josef Chochol, Emil Filla, Josef Gočár, Vlastislav Hofman, Pavel Janák, Zdeněk Kratochvíl, Otakar Kubín, Bohumil Kubišta, František Kysela, Antonín Matějček, Antonín Procházka, Ladislav Šíma, and Václav Špála. With the exception of Kubišta, Kubín, and Matějček, they were soon joined in the Skupina by Karel and Josef Čapek, Otokar Fischer, Otto Gutfreund, František Langer, Václav Vilém Štech, Václav Štěpán, Jan Thon, and Zdeněk Wirth. Although these names will be unfamiliar to most American readers, they belong to the leading representatives of early-twentieth-century Czech modernism.

The secession from Mánes and organization of the Skupina was a declaration of generational independence. But for what precisely did the group and the generation it claimed to represent stand? This was always an open question. The Skupina never issued a common program or manifesto; the scope of its ambitions and the diversity of its members probably prevented it from doing so. It never unequivocally associated itself with any one theory, movement, or ism. Contemporary critics were confused too, struggling in vain to find a durable label for the new group’s activities. They bandied about diverse and often contradictory terms including, according to Čapek, “expressionism, neotraditionalism, antitraditionalism, neoprimitivism, cubism, tetrahedrism, cylindrism, futurism, neoclassicism, and neoidealism.”12 And yet there was one style, one ism, that carried far more weight than any of the others—cubism—but its place and meaning within the Skupina were not uncontested either. In fact, it was the attempt by certain members of the Skupina to enforce a particular style based exclusively on the art of Picasso and Braque that caused the most substantial rift the group would suffer. In the fall of 1912, little more than a year after the group’s formation, the Čapek brothers, joined by the architects Josef Chochol and Vlastislav Hofman and the painter Václav Špála, led a bitter exodus from its ranks in protest of this constraint. If the art of Picasso and Braque brought the group together, it also helped break it apart. Yet, in 1911 Picasso and Braque were the rallying point, and the championing of cubism in the Czech context remains the Skupina’s most important legacy.

Figure 1.7 The Skupina výtvarných umělců, December 1911. Standing, left to right: Vincenc Beneš, Otto Gutfreund, Josef Čapek, Josef Chochol, Karel Čapek; middle row, left to right: Josef Gočár, Vilém Dvořák, Vlastislav Hofman, Pavel Janák; František Langer, Jan Thon, Emil Filla. Courtesy of Památník národního písemnictví.

Paris

When the artists of the “young generation” set out on their own in 1911, it is not a coincidence that the destination at which they arrived was French. One of the chief reasons Czech artists were so receptive to cubism was their overwhelming Francophilia. With one eye fixed on Paris, they were quick to educate themselves in the latest French trends. Given that Paris was the center of gravity for all of European culture in the fin de siècle, the Czech orientation there is surprising only in that Prague lay well within the orbit of Vienna, and in those years Vienna was undergoing its own remarkable artistic and intellectual renaissance. But despite Vienna’s radiance, by the first decades of the twentieth century, the Czech preference for Paris was unmistakable.

Individual Czech artists, such as Alfons Mucha or František Kupka, had always traveled to Paris for training or to seek their fortunes, but in the decade before the First World War what had been a steady trickle turned into a flood. A majority of the Skupina’s artists lived or studied in Paris in these years. Josef Čapek was enrolled at the Académie Colarossi in 1910–1911. Karel Čapek spent a semester at the Sorbonne in 1911 (see figure 1.8). The sculptor Otto Gutfreund trained with Emile-Antoine Bourdelle in 1909–1910. The painters Vincenc Beneš, Emil Filla, Bohumil Kubišta, and Václav Špála all journeyed to Paris in the years before the war. Some, such as Otakar Kubín, who became famous in France as Othon Coubine, never returned. Young Czech artists continued to visit the museums and galleries of Vienna, Munich, and Berlin, and were drawn with some regularity to Italy as well, but nothing compares to the appeal that Paris exerted on them. If the anecdotal evidence is to be bel...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Introduction

- 1 Prague 1911: The Cubist City

- 2 Between Life and Form: Karel Čapek and the Prewar Modernist Generation

- 3 The Lessons of Life: Karel Čapek and the First World War

- 4 Art ≠ Life: The Čapek Generation and Devětsil in Interwar Czechoslovakia

- 5 The Self as Empty Space and Crowd: Karel Čapek and the Czechoslovak Condition

- Conclusion

- Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Index