eBook - ePub

Communal Modernisms

Teaching Twentieth-Century Literature and Culture in the Twenty-First-Century Classroom

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Communal Modernisms

Teaching Twentieth-Century Literature and Culture in the Twenty-First-Century Classroom

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Drawing from recent research that seeks to expand our understanding of modernism, this volume offers practical pedagogical approaches for teaching modernist literature and culture in the twenty-first century classroom.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Communal Modernisms by E. Hinnov, L. Rosenblum, L. Harris, E. Hinnov,L. Rosenblum,L. Harris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatura & Crítica literaria. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LiteraturaSubtopic

Crítica literariaPart I

The Influence of Photography and Film on Literary Communal Modernisms

1

Teaching Modernism through the Phantasmic Mother: Maternal Longing in Virginia Woolf’s Fiction and Gertrude Käsebier’s Photography

When I teach and write about literary modernism, I often focus on the modernist self who yearns for maternally-connected wholeness. The medium of photography in particular invites undergraduates studying the literature and culture of this period to reconsider the literary text through the lens of the visual—a mode they often feel more comfortable analyzing and thinking critically about both in classroom conversation and on the pages of their writing assignments. Postmodern photographic theorists Roland Barthes and John Berger, as I explain to my students, discuss the ways in which a deep interaction between viewer and photograph creates a dynamic narrative, giving life to both the image and the viewer. For Barthes, this is especially evident in the deep relationship between the photographic image, memory, and the ideal of the maternal bond: “For me, photographs . . . must be habitable, not visitable. This longing to inhabit, if I observe it clearly in myself . . . is [ph]antasmic, deriving from a kind of second sight which seems to bear me forward to a utopian time, or carry me back to somewhere in myself, . . . awakening in me the Mother (and never the disturbing Mother)” (Barthes, Camera Lucida 38–40). Photographic meaning is an ever-shifting collaboration between the subject of the photograph and the photographer where the subject might reveal a transcendent essence. This exchange creates a dynamic, triangular narrative that elucidates the encounter between photographer, viewer, and subject, giving energy to both the image and the viewer. As I will establish in my interpretations of photographs and fiction associated with Virginia Woolf’s opus, the early modernist cultural work of Gertrude Käsebier exemplifies an idealized, maternally-bonded utopia. In positioning these intertexts alongside each other for our consideration, this essay will follow the pattern in which I introduce them to my students.

In this essay, I compare Käsebier’s late-Victorian photography to maternal moments in Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927) in order to show that both artists made use of maternal longing in envisioning wholeness through their art. The work of these modernist women artists reveals an aesthetic of interconnectivity, represented through the evocation of textual moments that inspire turn-of-the-century nostalgia, which resists death and reaffirms a wholeness of self by recreating memories of maternal bonds. Woolf alternately longs for and struggles against the phantasmic maternal embodied by images of her mother, Julia Duckworth—especially in To the Lighthouse. In this novel, the “wedge-shaped core of darkness” (62) that artist Lily Briscoe negotiates in her finished painting exemplifies the maternally-connected understanding of a whole self. This chapter will reveal—through a series of triangular relationships between mother and child, artist and vision—that the reader/viewer is invited to recreate the maternalist moment when engaging with these modernist texts. Finally, by emphasizing interpenetrations between Käsebier’s late-Victorian camera work and Woolf’s maternally-focused fiction, I suggest a reading practice in which we, as teachers, scholars, and students alike, strive to realize the potential of aesthetics in revealing the coequal presence of self and other, both in literature and in life.

Let us begin by looking closely at a plate from the Stephens’s family photo album of Julia Duckworth Stephen with her daughter Virginia taken by Henry H. Cameron some time in 1884 (Figure 1.1). Much of this album is available online on the Smith College Mortimer Rare Book Room archive (http://www.smith.edu/libraries). A very similar photo of Leslie Stephen holding his first daughter, Laura, attests to the conventionality of the pose. Nevertheless, this particular image patently illustrates a photographic moment of maternal bonding. Virginia, about two years old, poses with pleasure in the sanctuary of her mother’s nurturing arms. Julia bends her head slightly toward Virginia in a gesture of deference and love; Julia appears contented yet protective of her daughter. Their black velvet dresses, with matching buttons and similarly lacey detail, and their hair, parted in the middle, mirror each other, suggesting the closeness of this mother/daughter dyadic embrace. Diaphanous white light contrasts with the black dresses and background and emphasizes the luminous halo surrounding this mother and child, further indicating that the connection between mother and child is otherworldly. Virginia’s wide-eyed look back at the camera illustrates the fact that although she is comfortable within her mother’s embrace, she, like any precocious toddler, looks ahead to her own independence.

Figure 1.1 Julia Stephen with Virginia on Her Lap, 1884, by HH Cameron. Reproduction of plate 36f from Leslie Stephen’s Photograph Album. Original platinum print (20.0 × 14.0 cm). Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

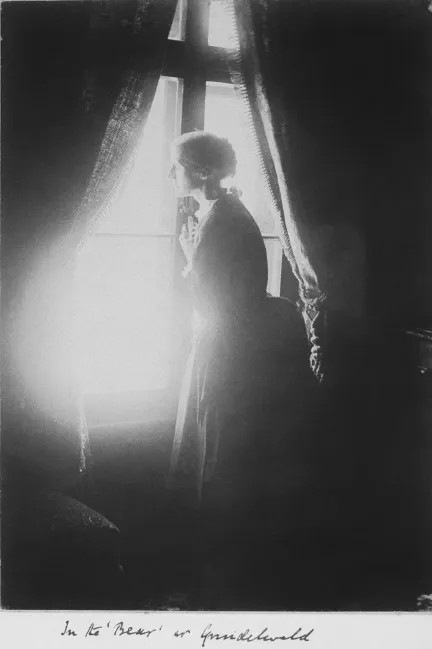

Woolf’s memory of her childhood consciousness is intense, as she demonstrates in the essay “A Sketch of the Past”, where she describes profound memories of her childhood at St. Ives. Woolf remembers sitting in her mother’s lap and lying in the nursery listening to the amniotic flow of the ocean waves outside her window: “If life has a base that it stands upon, if it is a bowl that one fills and fills . . . then my bowl without a doubt stands upon this memory. . . . It is lying and hearing this splash and seeing this light, and feeling, it is almost impossible that I should be here; of feeling the purest ecstasy I can conceive” (171–2). This image and this passage attest to Woolf’s deep understanding of the maternal union and its significance in her life and art, and they make a vivid introduction to reading and discussing To the Lighthouse in the undergraduate classroom (Figure 1.2).

Here it also becomes important to place the phenomenon of photography in its cultural and historical context. It is no coincidence that photography came of age at the same time as ethnography, cartography, modern imperialism, criminology, sexology, and psychoanalysis. However, photography of the modernist period did not always exemplify the desire to master reality through vision by categorizing others according to agreed upon stereotypes that these disciplines encouraged. In fact, various photographers of the era envisioned their medium as an art form that could communicate concepts of unity and harmony. Likewise, for many modernists, the photograph stands for a mystical, intersubjective experience, revealing the intensity of the moment; by blurring boundaries between subject and object, a fleeting union between seer and seen seems possible. Here I might refer students to documented contemporary comments about the universalizing potential of the photographic image by such luminaries as AL Coburn and Alfred Stieglitz.

Gertrude Käsebier, though not as widely known as her teacher and colleague Stieglitz, holds a significant place within the history of photography. In the late 1880s, Käsebier (1852–1934) became successful as a New Woman photographer; she is best known as a portrait photographer and Photo-Secessionist aligned with Stieglitz. Both artists were part of a group of photographers that called themselves pictorialists, the first proponents of art photography as a medium that could transform the world. Influenced by Impressionist painting, pictorialists created diffused and romanticized photographs—often manipulating their images through stage-managing, costuming, and retouching—in order to elicit passionate emotional responses from viewers. These photographic moments echo those pictured by Woolf’s great aunt, the eminent Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, and, further, feature the kind of matrixial encounter Woolf offers readers through her fiction.

Figure 1.2 Julia Stephen at the Bear, Grindelwald, Switzerland, 1889. Reproduction of plate 39c from Leslie Stephen’s Photograph Album, by Gabriel Loppé (1825–1913). Original silver print (7 × 7 cm). Presented by Quentin and Anne Olivier Bell, Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

I will discuss two photographs of Käsebier’s where maternalist moments similar to those envisioned by Woolf are present: The Manger, or, Ideal Motherhood (1899) and Mother and Child (1899). Although Käsebier almost exclusively privileges the white woman’s maternal gaze in her camera work, she also summons the possibility of a more open vision of the mother–child bond. Through her use of soft techniques and intimate camera angles that invite the viewer’s empathetic perception, her photographs represent maternalist flashes of intersubjectivity.

The Manger (Figure 1.3) displays the ideal of incandescent unity with the maternal body. Through Käsebier’s use of velvety pictorialist lighting, the viewer is allowed a glimpse of the ethereal, almost otherworldly bond between a mother and her baby, who is cradled closely to her breast. In the image’s consciously constructed blissful glow, a protective gauze (symbolic of the amniotic sac) enshrouds them both, emphasizing their symbiotic harmony. The subjects’ explicitly physical connection—the mother appears to be nursing her child—further emphasizes the tenderness of this maternal moment of interplay. In the course of this analysis, I also remind students of the Angel in the House ideal and the cult of motherhood as prevalent ideologies of the late-Victorian period. With all of its resplendent performativity, this image, which depends so heavily upon timeless conceptions of Madonna and child iconography, is emblematic of the early twentieth-century photographic maternalist moment.

Mother and Child (Figure 1.4) expresses the intimate, telescoping bond between the mother and the babe as well. The baby girl is innocently and cherubically naked, while the mother, draped in an Arts and Crafts style robe, crouches over her, lovingly supporting her chubby hands with her own reassuring maternal grasp. Both mother and child actively relish the covenant of maternal body and child, yet the child is allowed a Blakean sense of freedom—here visually represented in the turn away from her mother. Significantly, in this photograph, the child is afforded agency within the maternalist space. As Barbara L. Michaels notes,

While Käsebier’s children are not retiring, neither are they rebellious. They are always attractive, well-behaved counterparts to mothers who appear to be good, kind and patient. In Käsebier’s idealized world, granting independence to children seems to be part of a mother’s duty . . . because Käsebier seems to have embodied some of the precepts of Freidrich Froebel . . . [,] the German founder of the kindergarten movement [who] believed that mothers . . . should foster children’s intellectual growth and independence beginning in infancy. (82)

Figure 1.3 Gertrude Käsebier. The Manger, or, Ideal Motherhood, 1899. Platinum print (12½ × 10 in). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C./Art Resource, N.Y. Gift of Charles Isaacs.

Figure 1.4 Gertrude Käsebier. Mother and Child, Posed by Mrs. Hewitt and Her Daughter, 1899. Glass dry plate (8 × 10 in). Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-12048. Gift of Mina Turner, 1964.

Although the subjects in Kasebier’s pictures languish in the exquisite moment at hand, there often remains an awareness (reflected in the earlier image of Virginia and Julia) and even an acceptance of the fact that a division must eventually occur.

As I intimated earlier, the maternalist space encourages a kind of triangular process of reading. Here I gloss for my students more current feminist theories on photography (Laura Wexler, E. Ann Kaplan, and Judith Fryer Davidov). For instance, Davidov looks for the interval between self/body/Other that can be negotiated to create openings, possibilities of encounter, and photographic ambiguity through the lenses of women photographers. Informed by such feminist analysis of photography, we cannot ignore Käsebier’s complicity in replicating the Angel in the House ideal of her day. The mother/child composition, of course, has a long tradition in religious painting, which both novelist and photographer are taking into account. Certainly this point should also be pursued with students. Yet it is problematic to read Käsebier’s photographs exclusively as markers of a totalizing Madonna and child iconography or white imperialist dominance or restrictive bourgeois domesticity. Instead, as I suggest, Käsebier’s photographs of mothers and children can be read as monuments to the transcendent possibility available in the maternalist moment. This is not to say that Käsebier does not operate within nineteenth- and twentieth-century social and political ideologies to access a “universal” belief in the supposed “natural” roles of white mother and child. Nevertheless, it is feasible for viewers today to decipher them in a more open, less deterministic light. In Gertrude Käsebier’s pictorialist art, we can begin to see how a phantasmic maternal presence becomes the catalyst for self-revelation and connection with community. Like Virginia Woolf’s fiction, Käsebier’s photographs can reconnect viewers with a powerful instance of wholeness that eliminates restrictive borders between adult self and child self, and potentially self and other.

Once I have introduced students to this idea of maternal wholeness in Käsebier’s camera work, we return briefly to Woolf’s biography. Woolf’s memories of her mother Julia punctuate and expand as residues throughout her literary work. Her mother’s early death meant that Julia became a phantasmic mother, someone who can only exist as an image, and was therefore one whom Woolf was compelled to replicate in her fiction. It is my contention that the mother–child bond is fully represented throughout To the Lighthouse (1927) in the interactions between Mrs. Ramsay and her children. Early in the novel, as Mrs. Ramsay knits while caressing her son James, she simultaneously creates a balmlike, supportive, life-giving power. As she senses that her husband is “demanding sympathy”, she shores up her feminine verve for the task at hand:

Mrs. Ramsay, who had been sitting loosely, . . . braced herself, and, half turning, seemed to raise herself with an effort, and at once to pour erect into the air a rain of energy, a column of spray, looking at the same time animated and alive as if all her energies were being fused into force, burning and illuminating . . . [with] this delicious fecundity, this fountain and spray of life. (37).

This extraordinary fluid force is “her capacity to surround and protect” (38), her ability to “combine” (39) and create permanence with her vast maternal vigor. Its associations with “rain” and the “spray” of water once again...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Teaching Twentieth-Century Literature and Culture in the Twenty-First Century Classroom

- Part I The Influence of Photography and Film on Literary Communal Modernisms

- Part II The Politics of Communal Modernisms

- Part III Reinvention within Communal Modernisms

- Afterword: Some Notes on Radical Teaching

- Index