![]()

1

Introduction

Carolyn M. Byerly

Women have long held the notion that if they could somehow wrest control of the newsmaking apparatus, they would have a better chance of being seen and heard. One of the earliest and fullest expressions of this view is attributed to 19th-century US suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony, who addressed a crowd in 1893:

We need a daily paper edited and composed according to woman’s own thoughts, and not as a woman thinks a man wants her to think and write. As it is now, the men who control the finances control the paper. As long as we occupy our present position we are mentally and morally in the power of the men who engineer the finances … Horace Greeley1 once advised women to go down into New Jersey, buy a parcel of ground, and go to raising strawberries … I say, my journalistic sisters, that it is high time we were raising our own strawberries on our own land.

(Sherr 1996, pp. 203–204)

Anthony advocated women’s ownership as the means to control news content, concerned as she was about the mainstream press’s stubborn refusal to cover women’s campaigns for suffrage and other civil rights in that era. Ownership, management and increased participation in all aspects of news production have echoed through the last two centuries as the remedies for women’s invisibility and silence in mainstream news. In these same years, news has remained mainly under men’s ownership and control the world over, representing what cultural studies scholars call a longstanding ‘site of struggle’ where women have challenged men’s authority over news operations by demanding better coverage of issues that affect them, as well as women’s contributions to and leadership in nation building. In addition, they have demanded an open door to the profession.

The length, breadth and nature of women’s challenge to the news industry is evidenced in the international scholarly literature, which examines and critiques women’s omission and misrepresentation in news, and notes signs of progress; in the work of popular feminist movements that have consistently sought greater, more accurate representation in content; and in the demand for jobs for women within the reporting and decision-making ranks. Feminist media activists the world over have made it their explicit mission to address all of these – ownership, management, representation in content and increased access to jobs in reporting and editorial roles within newsmaking (Byerly and Ross 2006).

Goals of the book

This book is concerned with the last of these – women’s jobs within the news industry. Taking both its inspiration and substance from the Global Report on the Status of Women in the News Media (Global Report) (Byerly 2011), the book considers women’s situation within traditional news companies in 29 of the original 59 nations that the Global Report included. Nations were selected for the present book based on their robustness of findings, and thought was given to fairly even representation across the regions of the world. The data from these nations illustrate what the study found in terms of both problems and triumphs that women experience in newsrooms of medium-sized and large news enterprises in our contemporary times. Much is to be learned from delving into these findings, which also help us to pose new questions about women’s relationship to industries that have so much to do with shaping public opinion, understanding, social participation and connectivity among human populations.

The book has three ambitious goals. The first of these is to help fill a gap in feminist journalism scholarship with a well-researched, carefully analyzed account of women’s occupational status in news organizations around the world. Feminist scholarship produces little empirical (i.e., data-driven) research on women’s relationship to media internationally; and while mainstream journalism scholarship sometimes does provide such, it typically fails to adequately theorize gender relations associated with the numbers. The book’s second goal is to present a series of 29 national studies that offer detailed scenarios of how women in journalism are faring in unique national contexts. Each of these chapters situates data about women’s occupational status, terms of employment and company policies on gender equality – all as revealed in the Global Report study – within the broader context of laws, economy, history, culture and women’s status in the nations. Last, the book considers women’s status in news today within the broader contours of women’s historical struggle for full social participation, at both local and global levels. Among other things, the book seeks to address broader questions, such as where does women’s right to communicate enter into women’s long-term search for self-determination, and how has women’s media activism functioned in this historical process?

Content and structure of the book

The statistical data in this book will be drawn primarily from the Global Report, published in March 2011. That publication reported the findings from a study of 522 news companies in 59 nations. Whereas the original Global Report was a technical report rich in statistics, the present book strives to place data from about half of those nations within a context of new, original narratives composed of details about each nation. In other words, women’s status in those 29 nations’ news companies (as revealed in the Global Report research) will be interpreted within a broader, deeper framework of analysis than the original 396-page report was able to accomplish. In all chapters, authors present additional data from their own or other research, as well as a range of other factual information to flesh out the picture of women journalists in newsrooms.

The book begins with two chapters that provide the intellectual framework for the detailed chapters to follow. This introduction offers an overview of the book’s contents and direction. The chapter that follows considers the forces that shape women’s status in a rapidly changing profession, but a profession that still claims a place of importance in societies around the world. That chapter assumes that women’s advancement in institutions (e.g., media) matters and that their progress can only be understood by considering it within the complex matrix of economic systems, political structures, laws, technology, cultural traditions, women’s rights movements and the routines of journalistic practice.

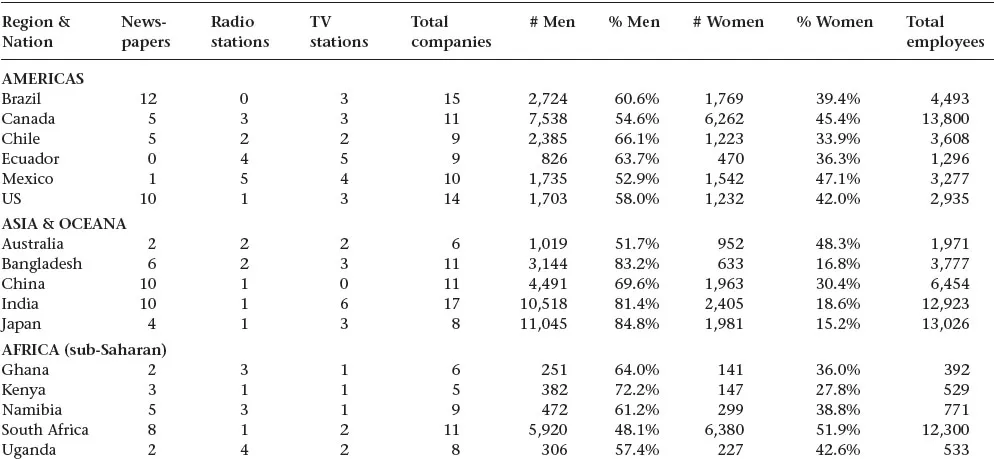

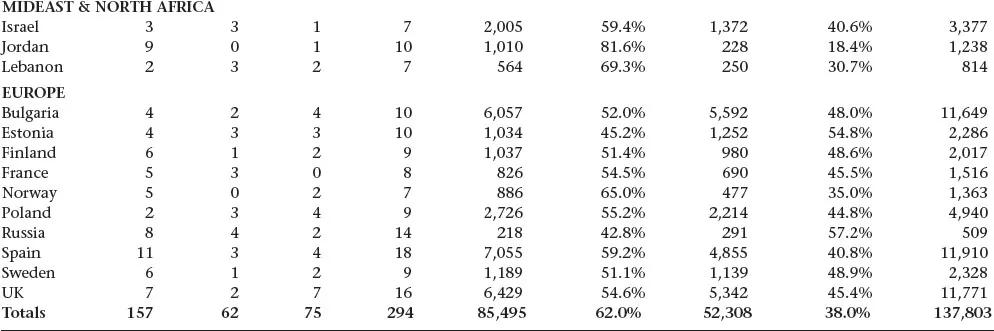

The subsequent chapters providing the 29 national case studies are each authored by researchers and/or journalists from these respective nations. Most of the authors served in a research capacity for the Global Report study; in nearly all cases, they are native to the nations they write about. Bringing personal and professional familiarity to their task, they are able to offer anecdotes, examples and stories to illustrate the statistics that define women’s status in news for their respective countries, as revealed in the Global Report. While this book includes only about half of the original 59 nations, the number of employees these represent comprises 137,803 (81 per cent) of the original study workforce of 170,000. Therefore, this smaller set of nations substantially represents the original study’s database. Table 1.1 provides a statistical summary of the range of media included for each nation and the number of employees by nation, with percentages for men and women.

Chapters containing national case studies are organized into four parts, or sections, to provide something of a comparative guide to women’s status in their newsrooms. There is no ideal (or possibly fair) way to rank nations, and thus the grouping of nations in those sections should be read with an open mind. Indeed, there has been considerable progress for women journalists in all nations included in this book in recent decades, as the authors point out. At the same time, women in the profession even in the best case nations continue to experience varied challenges – most having to do with the entrenched nature of patriarchal (male-domination) norms, values, attitudes and the practices borne of these. It is useful, nonetheless, to denote the nations in which women have made truly significant inroads into newsroom roles and decision-making, as well as to identify the nations in which historical events, traditions, customs, women’s roles or other factors have made such progress slower. These two extremes are fairly readily identifiable; more difficult to designate by levels of progress are the nations that fall along a jagged continuum between them. Thus, the nations organized into Parts II and III are, perhaps, less secure in their placement and one might consider them as even interchangeable in some cases. Designations were made following a systematic review of all 29 chapters, considering factors such as the glass ceiling; women’s placement in governance and top management in relation to other roles they filled; the number of men versus number of women; newsroom policies; and the broader context of press freedom, national laws on gender equality and women’s status nationally.

Table 1.1 Composite figures for national samples and employment figures by gender

Source: C. M. Byerly (2011), Global Report on the Status of Women in News Media (International Women’s Media Foundation).

This process revealed, among other things, how complex women’s standing in journalism actually is in all of the 29 nations. How should Israel, for example, be placed? Researcher Einat Lachover found no glass ceiling among the seven companies she surveyed, and a third of those in governance and top management roles are women. In addition, women are near parity with or even surpassed men in some newsroom roles, most notably production and design where they comprise about 60 per cent. In fact, women are relatively well distributed among the different job levels, in spite of the fact that they are slightly fewer in number than men overall in these companies. Most women (like men) are in full-time, regular employment, though men are more likely to be in regular, full-time employment than women, and companies had adopted few policies on gender equality at the time of the research. In the larger field of journalism, there are a few women ‘stars’, but overall, the numbers of women are small. Advancement within the field of journalism in Israel relies more on personal ties than on performance. While Israel has adopted equality laws, the government does not enforce them – as illustrated by a gender-segregated workforce, for example. Moreover, Israel’s heavily ‘militarized society’ marginalizes women, according to Lachover, and the lack of a strong feminist movement does not benefit women in their professional lives (including journalism). In spite of the challenges in society as a whole, women at the companies Lachover surveyed had managed to do relatively well in terms of job roles and levels of decision-making, suggesting they are ‘making substantial progress’. Some might argue, perhaps, that the difficulties Israeli women journalists face in both their profession and society suggest they are rather ‘negotiating the constraints’. This example (one of many that might be cited) illustrates the difficulty of creating a reliable hierarchy of progress among nations.

The final chapter reviews the information provided by the national case studies contained in Parts I–IV within an analytical framework informed by feminist political economy, history and cultural theory. Among other issues, this chapter asks how gender enters into financial ownership and management arrangements in media industries that are, in most nations, either heavily concentrated or moving toward concentration. In addition, the chapter considers the ways that feminist activism within media industries might influence their organizations at a time when ownership patterns and shifts in technology are bringing about a rapid convergence of communication patterns everywhere. The role of women journalists in this convergence process, as well as what it might mean in terms of the future of their profession, is examined using a range of data and indicators.

Related research

For some years now, there has been a growing need for reliable statistical data on women’s occupational status within newsmaking operations around the world. Margaret Gallagher (1981) was among the first to point out the problems of women’s employment in media, and her more recent work, An Unfinished Story: Gender Patterns in Media Employment (Gallagher 1995) provides the only other broad international study of women’s status in media employment before the Global Report. For that earlier study, Gallagher examined 239 companies (both news and other forms of media) in 43 nations. Her work endures and offers a useful baseline against which to compare Global Report findings. Recent regional and national studies include Ammu Joseph’s (2005) Making News: Women in Journalism (2005); a number of short regional reports in Paula Poindexter, Sharon Meraz and Amy Schmitz Weiss’s (2008) collected volume, Women, Men and News: Divided and Disconnected in the News Media Landscape; Louise North’s (2009) The Gendered Newsroom; and Pat Made and Colleen Lowe Morna’s (2010) Glass Ceilings. The last of these, Made and Morna’s Glass Ceilings report, contains the findings from the Gender Links organization’s similar study to that of the Global Report. Gender Links, a Johannesburg-based advocacy and research group concerned with gender equality in media, conducted a study of women’s media employment in 16 sub-Saharan nations that had used a comparable methodology to that of the Global Report. Both studies were conducted within a similar time frame. Through a cooperative arrangement, the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) was able to acquire Gender Links’ data for inclusion in the Global Report.

Methodology in the Global Report study

The Global Report was a ‘first’ in several ways with respect to women-and-journalism research. It represents the only study to date that has surveyed news companies across the world using an overarching research design and a single instrument for data collection. It is also the largest, most comprehensive study on women’s status in the news industry globally. In addition, the study focused solely on news media (both print and electronic), emphasizing the importance of the journalistic enterprise and women’s place in it. The study employed the largest research workforce in any study of women and news – more than 150, most of whom were located in the nations of the study.2 Of those, all but a handful were either working journalists or academics with former journalism experience, enhancing the chances that they understood and could competently conduct their data-gathering tasks. Staffing for the study also included three statisticians, two project assistants, two graduate interns and myself, the principal investigator. Both local researchers and project staff were compensated for their services – a detail that should not be overlooked for its importance in a study of this scale. In addition to the project personnel, the core IWMF staff supported the project with fundraising, financial services and logistical assistance.3 The project was funded by Ford Foundation, the Loreen Arbus Foundation, UNESCO’s Communication and Development Division and Information Center and the McClatchy Company Foundation. The project was housed at the IWMF headquarters in Washington, DC, where all original data for the pr...